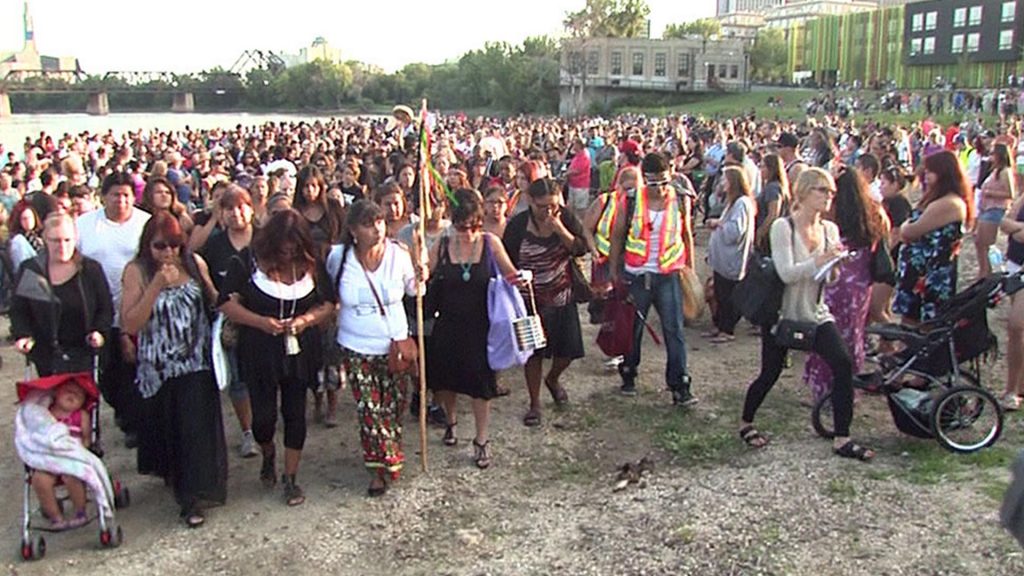

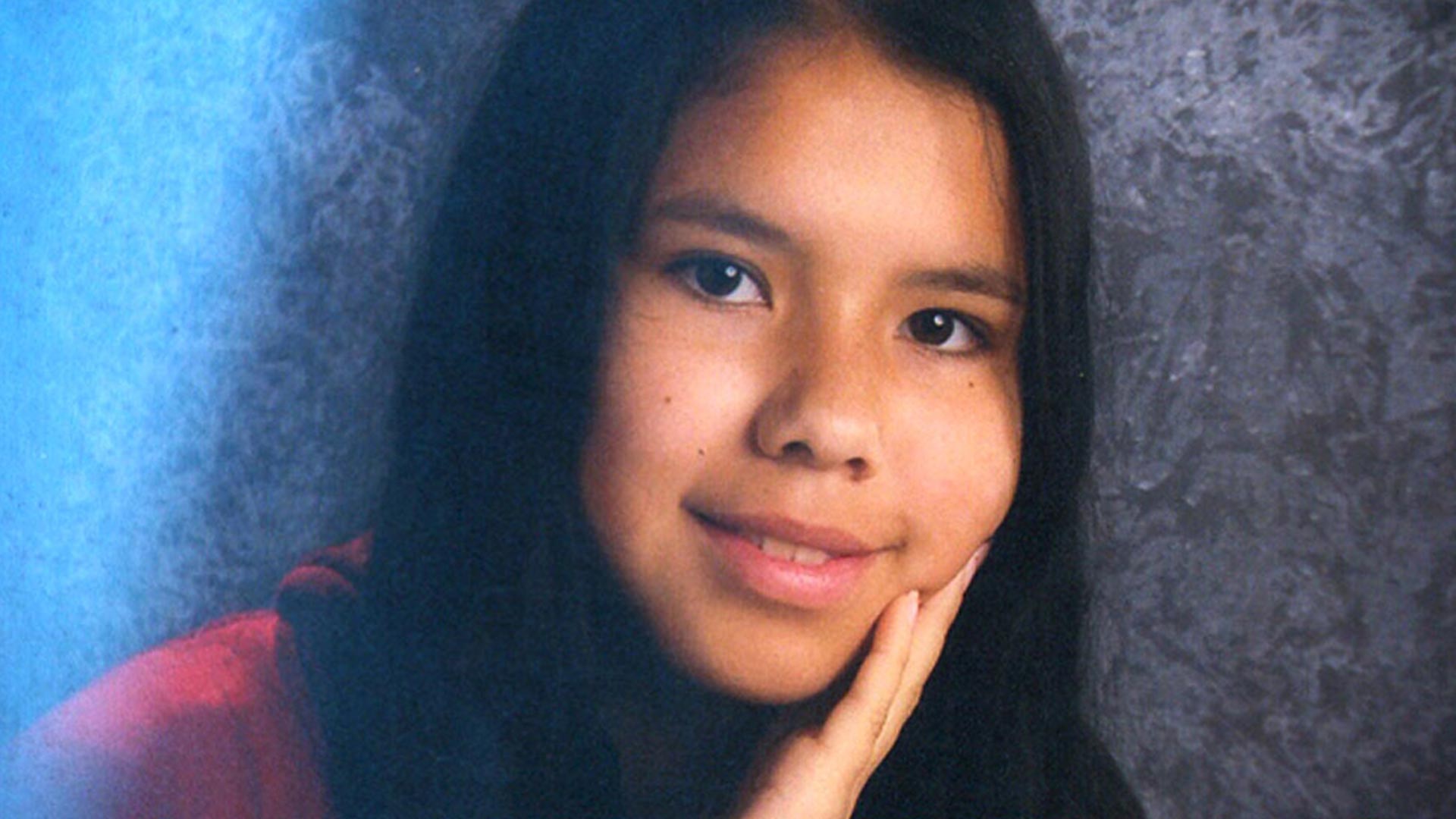

The death of Tina Fontaine inspired marches and a national inquiry. APTN file

Thelma Favel is “very, very disappointed” the Trudeau government isn’t unveiling an action plan today to help protect Indigenous women and girls like her niece Tina Fontaine.

The 2014 death of Fontaine, who was 15 when she went missing in Winnipeg and later found dead in the Red River, helped push politicians towards a national inquiry that produced a 1,200-page report released June 3, 2019.

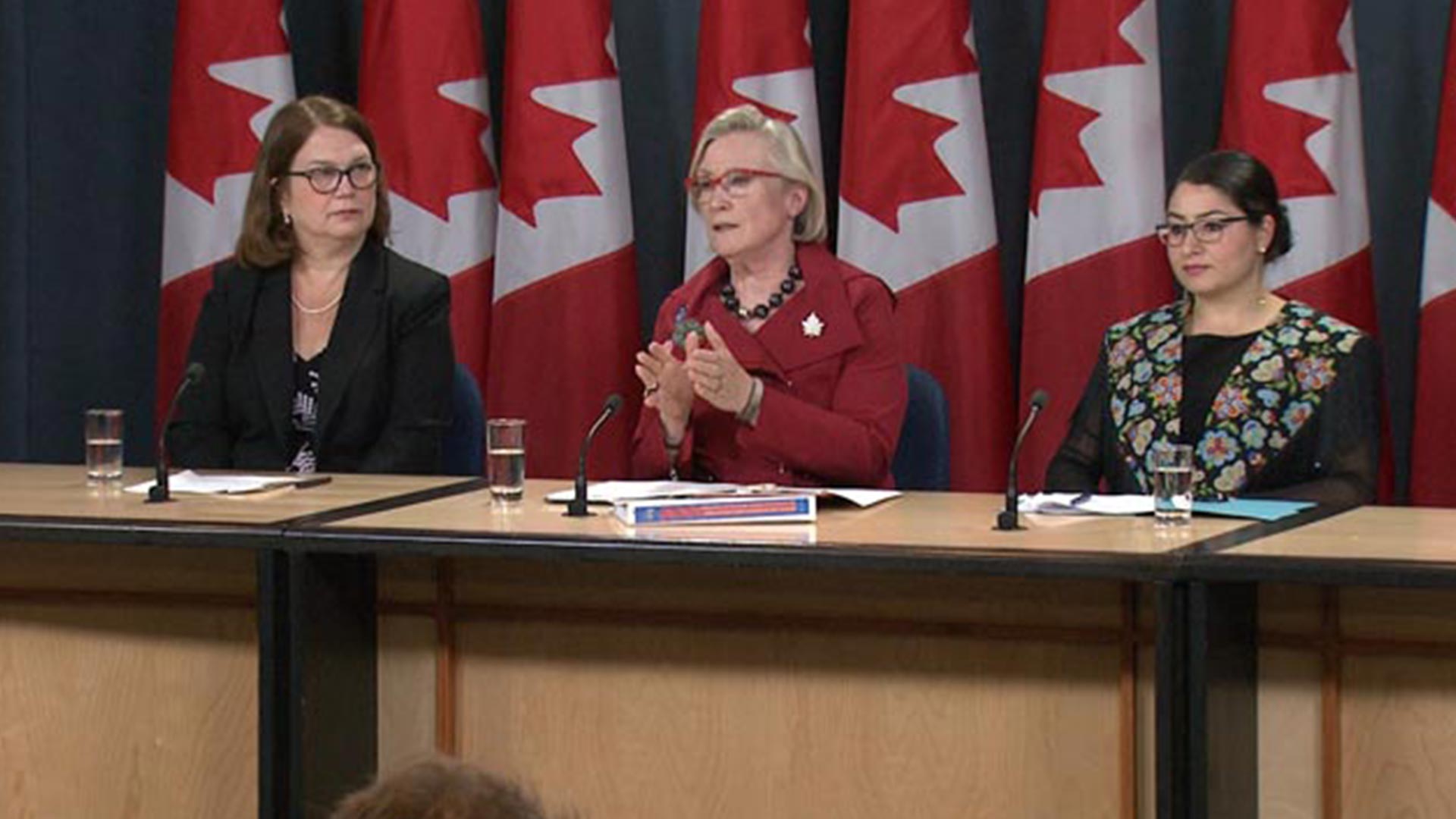

But its promise to deliver an action plan one year later on how to fund and implement the report’s 231 calls to justice was interrupted by the novel coronavirus health emergency, said Crown-Indigenous Relations Minister Carolyn Bennett.

Leaving Favel, from Manitoba’s Sagkeeng First Nation, fearing the worst.

“It was a waste of time and money,” she said of the nearly $100-million and three-year probe into the root causes of violence against Indigenous women and girls.

“They’re trying to get rid of us and our culture.”

Favel attended the final report ceremony in Gatineau, Que., with Assembly of First Nations (AFN) Regional Chief Kevin Hart and her friend, former Sagkeeng band councillor and activist Marilyn Courchene.

When Favel appeared on stage, she was accompanied by AFN National Chief Perry Bellegarde, who has become an ally to the cause.

“The Final Report of the National Inquiry confirmed what First Nations have known all along: First Nations women and girls are specifically being targeted for violence and that deeply ingrained institutional racism perpetuates this violence,” Bellegarde said in a statement to APTN News.

Courchene said the highlight of the event was women in the back screaming “genocide” when Prime Minister Justin Trudeau accepted the final report.

“They yelled it loud and proud,” Courchene recalled last week. “I said, ‘Right on!’ That’s the word.”

Courchene said the inquiry’s powerful conclusion of genocide sent her to research the original promises – the treaties.

“Where did this stuff start? All this jealousy and hate? We had relationships with two countries – French and English. All these women taken by the settlers to survive in Canada in the 1800s.”

Her research showed a litany of oppressive systems imposed by colonial governments: reserves, Indian agents, the pass system, residential schools, the ‘60s Scoop.

“All these bad things were learned within that system,” Courchene said, “assimilating not to be better but to be dysfunctional – blaming the parents and savages.”

Todd Lamirande spoke with Maggie Cywink about the anniversary

Yet without the women teaching the settlers they never would have survived, she said. But instead of being recognized and rewarded, Indigenous women were victimized and discarded.

And sexualized, the inquiry found. With police failing to investigate crimes against them and the child welfare system seizing their children, added Courchene, who has lost a niece to violence.

“It’s a sad thing to have to go through but the commissioners did their best,” she said.

“I wish Canada would say, ‘I’m sorry, I really feel you.’ Then that hurt would go away.”

The minister’s staff clarified to APTN that June was “a target” month for its action plan but “wasn’t a firm commitment.”

“We’re working hard at this,” added Bennett in an interview, who said a new government website will detail the work done to date.

“We’re expecting some disappointment.”

Bennett said she and Justice Minister David Lametti have been meeting virtually with advocates. She was optimistic this approach would result in a better action plan than hosting an in-person summit in Ottawa.

Bennett also seemed particularly taken with work done in the Yukon, where the territorial plan is called “Changing the Story.”

A spokesperson said the Yukon government was collaborating with various groups and wasn’t ready to reveal details publicly yet. But it did share some highlights with Bennett, who told APTN interest was building across the country “in what the Yukon was doing.”

This is welcome news for someone like Cheryl Maloney, who wants to see the national action plan guided by people on the front lines.

“This has become political,” said Maloney, former president of Nova Scotia Native Women’s Association and human rights advocate.

“We lost that power we had through advocacy and lobbying.”

Danielle Ewenin, whose sister Lainey Ewenin was found dead outside Calgary in 1982, said that spirit is still at work in Saskatchewan, which hosted a major grassroots gathering last fall to discuss a regional strategy and hopes to hold annual events.

“A group of families is writing a letter to force this into the international arena,” she said noting the Organization of American States would get a copy.

“I don’t think Canada is going to change its policies unless it’s forced to.”

Like Courchene, the inquiry’s final report inspired Inuk Laura Mackenzie to take a closer look at her history of growing up in Nunavut, where violence against women is many times the norm.

Mackenzie testified before the inquiry about child sexual abuse and suicide in the northern territory, and believes communicating the inquiry’s findings is key.

“A lot of Canadians are not aware of what’s going on,” she said in an interview.

“We need to educate Canadians about what’s still going on – and why.”