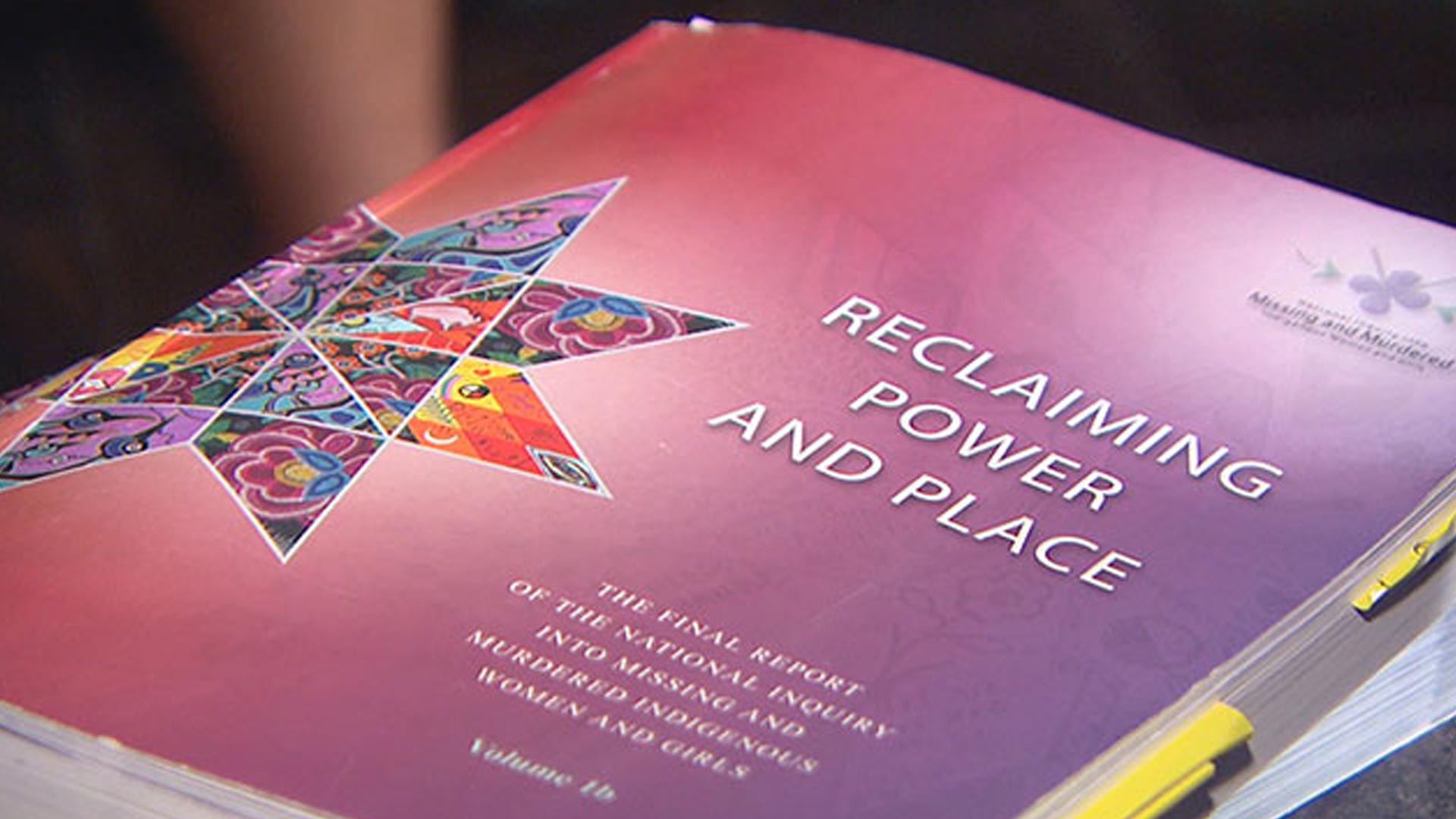

The media blowback was swift and fierce when Reclaiming Power and Place: The Final Report of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls was released a year ago.

But the commissioners weren’t surprised. They predicted the report might leak – which it did – and predicted the media and public would latch on to one word: genocide.

“It was exactly what I expected,” former commissioner Michele Audette told APTN News.

“Every media, every person that wasn’t sure or not in support of the Indigenous movement, reality, or worldview would jump on the word of genocide. We knew that. So, we said to ourselves, ‘Let them do that, and it’s just going to show that in 2019, at that time, that media has an important role to play as an educator promoting – or to tell the truth that came from the families and survivors.’”

Ink hit editorial pages in a hurry and analyses crossed the airwaves onto TVs and smartphones.

Many Canadian media argued the $98-million national inquiry – whose setbacks and flaws were thoroughly documented – was wrong to accuse the government of genocide.

“Well, they certainly didn’t pull their punches,” wrote The Toronto Star’s editorial board on June 3.

And neither did the pundits.

“Is the commission saying that the deaths of the 38 Indigenous women who, according to Statistics Canada, died by homicide in 2017 should be investigated under Canada’s Crimes Against Humanity and War Crimes Act, the law governing genocide?” wrote The Globe and Mail’s editorial board on the same day.

“If that seems ridiculous, it’s because the charge of a continuing genocide in Canada is absurd. It simply does not bear scrutiny in 2019,” the article said.

“Perhaps we need a new word to describe the ongoing harms of the colonial legacy. ‘Genocide’ isn’t it,” again wrote the Star’s editors on June 6.

“Yes. It is awful. But is it genocide?” asked CBC’s Michael Enright on June 8. “The problem with the term is complex and goes beyond mere pedantry. Its utterance has now become the most telling element in the fabric of the report. It has become a distraction. We might not be able to cite three recommendations of the report, but we have come to recognize that what happened to these women was supposedly genocide.”

The National Post’s Barbara Kay was also “too distracted” by the final report’s genocide finding.

“The message to Canadians in the MMIWG report seems to be that Canadians will never be allowed to wriggle off the hook of perpetual guilt. This is a no-win strategy: Canadians will lose interest in and motivation for reconciliation, and Indigenous people will remain culturally suspended in an unhealthy aspic of ‘impotent victimhood’,” she wrote on June 11.

But the person who penned the report’s legal analysis of genocide accuses the media of getting it wrong.

“This is completely incorrect,” said Laval University Prof. Fanny Lafontaine. “This is not what the inquiry said. The genocide is different acts and omissions across decades that aimed at the destruction of Indigenous peoples as a social unit. This explains the acts of violence against women and girls.”

A year of reflection has only strengthened her in that argument.

“After a year of having had conversations across the country with academics, with Indigenous peoples and non-Indigenous peoples, what we realize is that this word has slowly made its way into our collective history. And I think that’s because it’s the truth, and I think it works also in international law,” said Lafontaine.

The National Post declined APTN’s interview request to explain its position. The Globe and Mail did not respond at all. The Star also declined, saying the editorials speak for themselves and any assessment of the paper’s position should account for all the editorial commentary.

The Star, also on June 3, ran a competing editorial by Tanya Talaga, who was the paper’s Indigenous issues columnist, that argued along with the commissioners that genocide was an “inescapable conclusion.”

She thinks back on when the report was released and reaction from media.

“I remember feeling like something had hit my stomach you know, it just felt awful. I should have known that this was going to be the reaction from most of the mainstream media but it still came as a shock and a surprise and I don’t know why,” she told APTN. “I guess I was naïve to think otherwise but it was, it was pretty intense, that whole day was so intense.”

“But I reached out at the time and I said you know, I understand that the Star’s editorial, is supposed to, the editorial page is supposed to speak for the paper but this editorial does not speak for me.”

Talaga also testified as an expert before the commission for the final report’s 10-page “deeper dive” on media and representation of Indigenous women, girls and 2SLGBTQQIA (Two Spirit, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, questioning, intersex and asexual) people.

The report concluded that media often focus on criminality and negative stereotypes that dehumanize and perpetuate racism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia, and misogyny.

“What we found, not only in our research but also what the families and survivors told us in hearings, was that their lost loved one was portrayed with the headline of drug addict, street worker, prostitute, street person, sex trade worker – all of these very negative stereotypes,” former chief commissioner Marion Buller told APTN.

“In some cases, these women were not drug addicts. They were not street workers. In just about every case, they were a mom, a sister, a beloved family member, a member of a large community – very positive images that were completely overlooked, in fact ignored.”

In its 231 calls to justice, the national inquiry called on media, news corporations and “in particular, government funded corporations and outlets” to break down stereotypes that demean and hypersexualize Indigenous women and girls, hire more Indigenous reporters and support Indigenous people sharing their own stories.

How have we done a year later?

“I can’t say that there’s been a decolonizing approach adopted by those who make decisions about what stories go forward. I can’t say that I have seen a lot of new faces in the media. In fact, I’ve read in social media about Indigenous reporters who have left mainstream media,” said Buller.

“Can I give media in Canada a passing grade? No, I can’t.”

Audette says it’s hard to judge without a national action plan that includes and involves media across the country.

But Audette says she’s seen some positive changes: jobs pop up for Indigenous reporters, new hiring processes, a growing number of people who take the extra time to make sure Indigenous people are quoted properly.

“I think there’s still a lot of homework to be done or change. We saw a few changes since June last year with the media – but still not enough. And I’m anxious to see that shift but also not naïve that it’s not going to happen in one night,” she said.

For Carleton University Prof. John Kelly, who teaches journalism in the capital, there’s no debate around the word genocide.

He devoted much of his career to the work of revitalizing Indigenous language, tradition and culture. An elder originally from Haida Gwaii, he describes his career as an Indigenous journalist as an “uphill battle” and one that must continue.

“For so many years it’s been like three steps forward two back,” he said in an interview with APTN. “I get really discouraged about that and say, well it’s two steps back. But you need to consider that the three forward and two back is still one step forward. We know what we want to do.”

“Media are absolutely responsible for raising the consciousness in the country,” he said. “For the media to blast the very word, the only proper word to describe what happened to us, it’s just not right.”

Though Justin Trudeau first refused to use the word, he soon accepted “the finding that this was genocide.” But the commissioners didn’t just say what happened was genocide. They said “it is genocide.”

APTN put the same question to him a year later.

“I think the situation that has been faced by Indigenous Canadians for decades, for generations, for centuries is appalling and needs to stop. Many people have talked about cultural genocide, used very strong words for it,” he replied.

“There are lots of words that can be used. We need to use them and we need to move forward.”

For Lafontaine, though the prime minister won’t say genocide continues, his admission of past genocide was unprecedented and didn’t garner the attention it should.

“This is probably historical. Have you heard of a head of state that agrees with the conclusion that his state is responsible for genocide? This is big because what it means is that, once you have accepted the conclusion that it’s genocide and once you’ve seen that the acts spanning decades actually lead to genocide, it’s a legal responsibility in international law.”

She argues the report’s calls to justice aren’t mere recommendations but obligations under international law to rectify wrongs and make reparations.

Click here for complete coverage from APTN News: MMIWG

The Canadian government has apologized for residential schools and can point to a list of class-action settlements dealing with past colonial injustices: residential schools, the ’60s Scoop and Indian day schools.

That list could lengthen too. The government last year expressed intent to settle a class-action dealing with willful, reckless and ongoing discriminatory underfunding of the child welfare system on-reserve and the Yukon. But it also seeks a judicial review to quash the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal’s order pay the maximum allowable amount of $40,000 to children and family members harmed by the system.

An unidentified federal government official told CBC last year that Canada could expect to see the genocide finding used against it on the world stage.

“It’s difficult to imagine Beijing passing up the propaganda plum presented by the inquiry report and Trudeau’s response to it if, for example, Canada were to criticize its treatment of its Muslim Uighur minority,” wrote Evan Dyer in that article.

For Lafontaine, that’s the point.

“It does tarnish its (Canada’s) reputation – as it should. As current underfunding of different services, lack of water, lack of accountability for violence against women – it’s an ongoing genocide. So yes, it does tarnish its reputation,” she said.

For Kelly, it’s not a ‘propaganda plum,’ but the reality of life in Canada.

As an example that voices must be heard he pointed to the recent wave of demonstrations that brought Trudeau home from an international charm offensive. Indigenous people halted a portion of the national rail system in protest after RCMP conducted a militarized raid in Wet’suwet’en territory during a long-standing pipeline dispute.

“Unless we get the attention we deserve on this, Canada will never have peace. Canada will never have unity, will never be reconciled,” he said.