Warning: This story contains details about Indian Day Schools that may be upsetting. The Hope for Wellness Hotline can be reached 24 hours a day at 1-855-242-3310 or online at www.hopeforwellness.ca

To be a principal at an Indian day school, you had to be a numbers man.

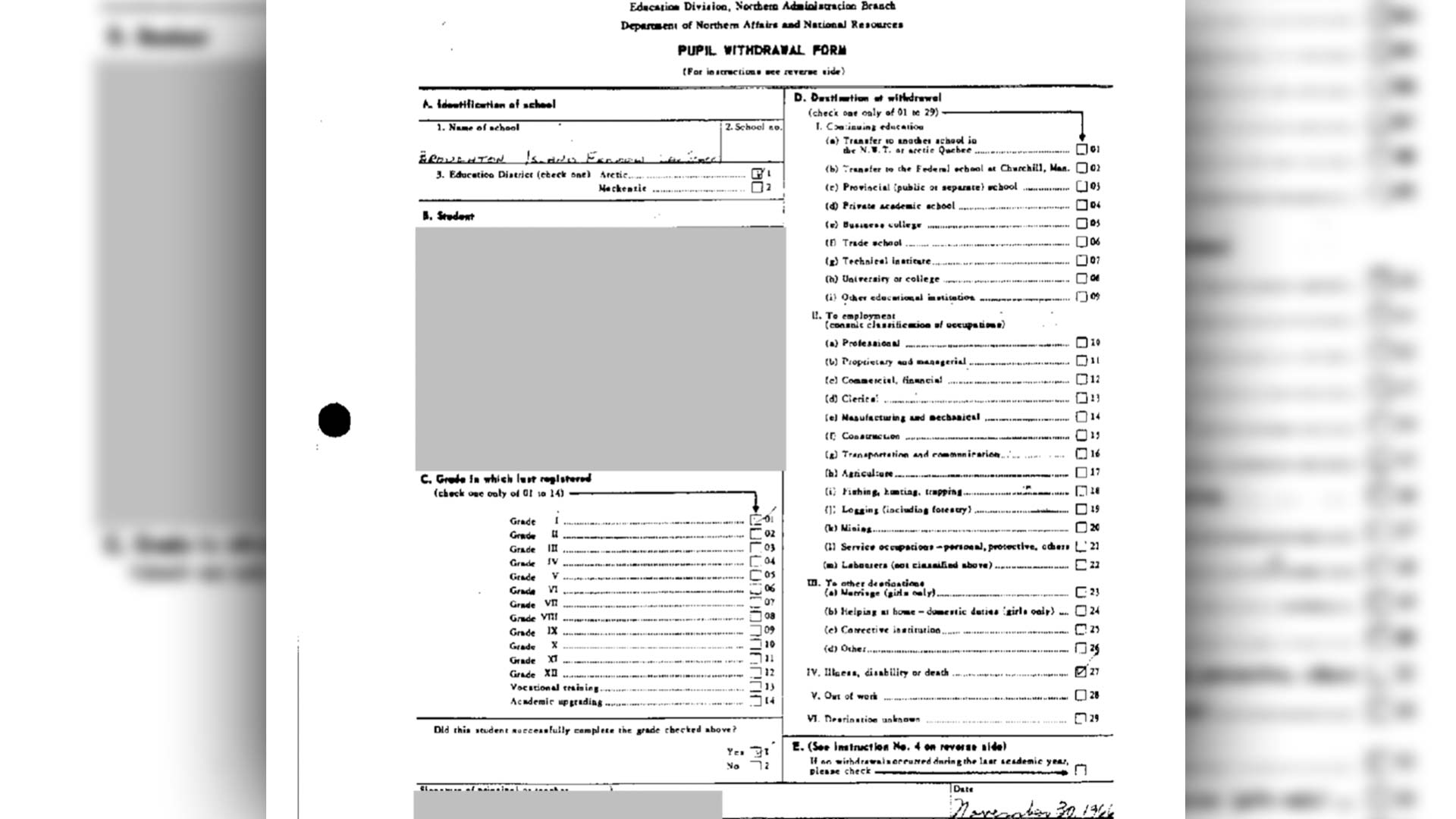

Historical documents obtained by APTN News show reams of forms, statistics and reports that heads of day schools were required to complete between 1916 and 1996.

There were forms for the middle of the month and forms for the end of the month.

There were forms for enrolment, forms for attendance and forms for reporting where Indigenous students went after abandoning the schools they were forced to attend as part of a federal government assimilation program.

APTN analysed the information in the 619 documents obtained from Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada via an access to information request.

The documents span the years 1916 and 1996, and reveal 200 students died at 46 schools or about 15 per cent of the 699 day schools Canada operated for more than a century.

Why APTN received only those documents was not explained.

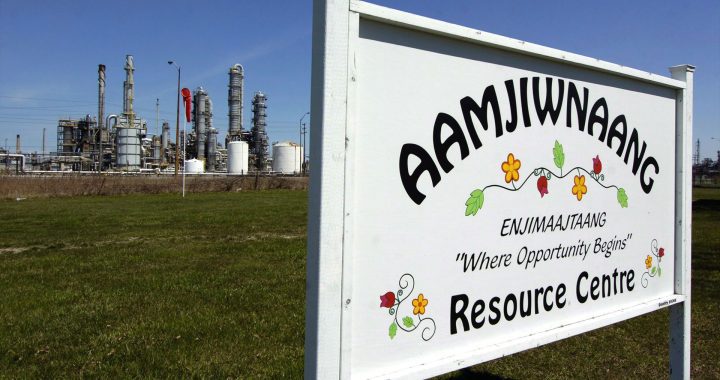

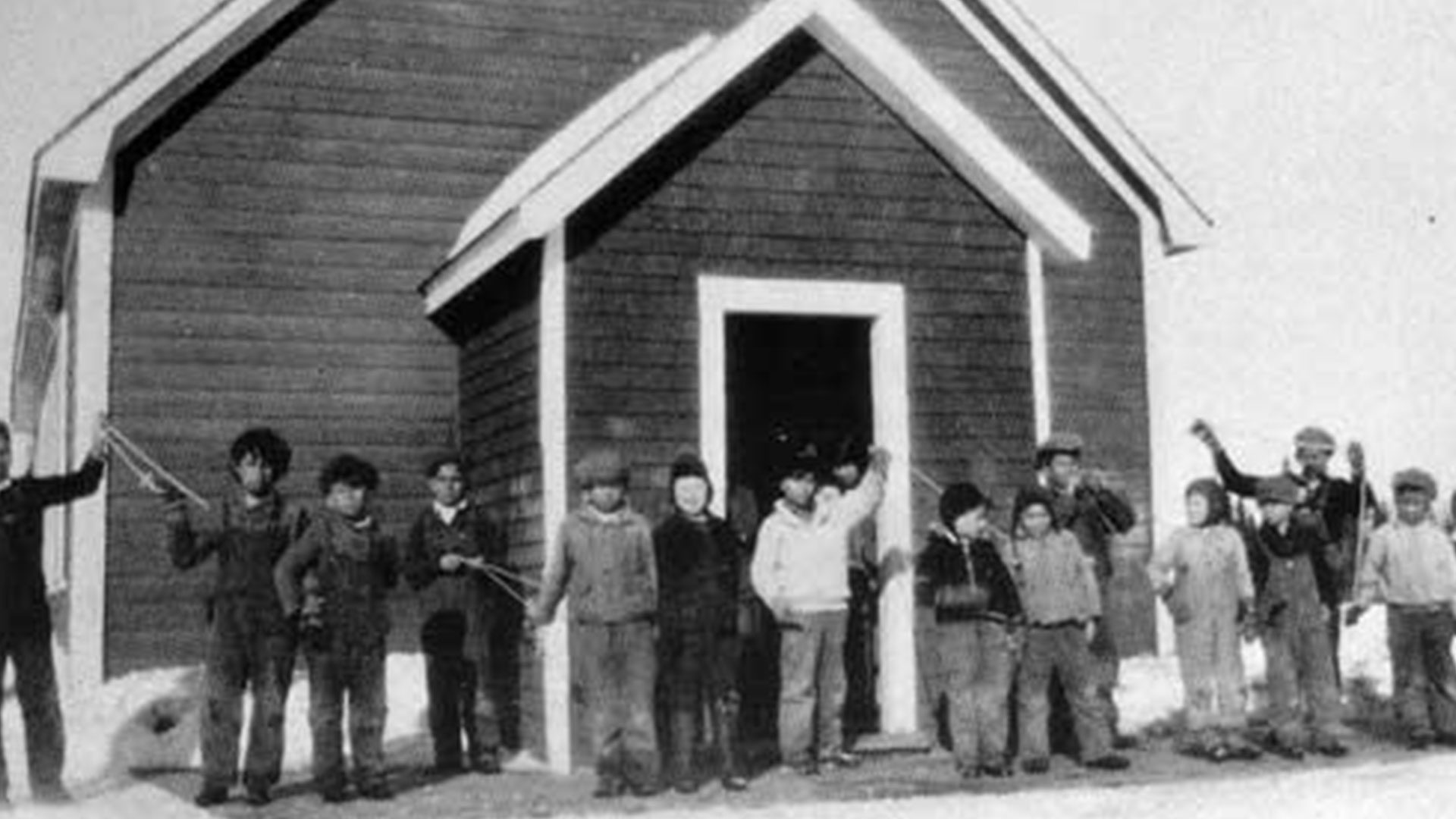

Day schools, where children were allowed to return home to their own beds at night, ran from the 1860s to the 1990s.

The so-called education system was expanded into a boarding model called residential schools from the 1870s to the 1990s, which ran parallel to day schools.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada concluded the system was a form of “cultural genocide.”

Day school survivor Ray Haipee was sent to Ucluelet Indian Day School in the 1960s.

He is still wrestling with the memories.

“It still comes back to me once in a while,” he told APTN. “And one of the band members says to me, ‘you’ll get over it.’

“No, you don’t get over stuff like that. It bounces around in there forever and ever.”

Federal inspectors managed the schools until clergymen/principals took over administration in the 1960s, the documents show.

Memos, reports and letters reveal principals – who were usually male – struggled with infrastructure and staffing challenges at the remote and rural day schools located on First Nations across the country.

For example, a log school built in 1892 had neither the heat nor power to handle the frigid winter conditions of northern Manitoba.

“Owing to the cold weather and the poor accommodation in the building now used for the school, the attendance was very irregular,” the documents quote an unnamed teacher as saying.

Still, a school inspector seemed satisfied.

“The school has a flag, there is plenty of good wood. One of the Indians, three years ago, brought an organ for the use of the school,” replied Insp. R. H. Cairns.

“This, to me, is strong evidence that the Indians are gradually becoming interested in the education of their children.”

The federal government was blamed for the 1977 death of a student in northern Manitoba after failing to deliver an emergency communication system, despite four years of lobbying.

“We are not requesting this any longer,” wrote an unnamed school superintendent about the need at the Lac Brochet school, “but, demand that a proper radio-telephone communication system, be installed immediately without further delay.

“Today, a young man died, while we were desperately trying to send out messages for help. We believe that proper communications [sic] is far overdue.”

But the biggest problem, according to the documents, was principals quitting due to burnout.

“Rev. J.S. Wilson is leaving Sioux Lookout at the end of the year,” reported Supt. Henry G. Cook.

“Due to lack of staff and the worry of trying to operate a school under such circumstances, the health of his wife has broken (she too was on staff) and he feels he can stand the strain no longer.”

Cook warned schools would have to close unless more clergy stepped up to fill the void.

And teachers were fed up too, he added.

“In nearly every (Anglican-run) school (in the West) staff members are disgruntled and some failing in health because of overwork,” Cook wrote.

“The fact now has to be faced that our church is not producing enough actively missionary minded people to man its schools and we have to hire people interested only in a job.

“These are Church operated schools and the Church must staff them adequately if it wishes to retain them as channels of spreading the Gospel,” he added.

No say

The documents show Indigenous communities weren’t given a say in what their children were – or by whom.

A 1916 annual report from Mistawasis Day School in Saskatchewan said students were learning “The Holy Scriptures, and Primary Catechism” with “special attention being paid to memorizing, and studying the Ten Commandments, The Sermon on the Mount, and other sections suitable especially to children.”

“Besides Hymns, patrotic [sic] songs are frequently song [sic],” the report added.

The documents indicate that changed in later years when the federal government transferred control of day schools to provinces and Indigenous communities and the religious element was removed.

This is the third in the three-part series Surviving Day School with APTN National News.