Accessing safe, affirming healthcare is difficult for transgender people across the country partly due to a lack of training say doctors and educators who are advocating for change.

“Even before stepping into the door, even before, you know, booking that appointment I think for lots of folks, especially within the trans community, there’s hesitancy and fear around the medical system,” says Racheal Wu, a sexual and reproductive health facilitator.

Through the Sexuality Education Resource Centre Manitoba, Wu teaches service providers how to be better allies to 2SLGBTQ* people.

“Often I have people asking about ‘can I just put, like, the rainbow sticker on the door’ or like say it’s an inclusive space and we always tell people it’s so much more than that,” says Wu, “ [it’s] making sure that staff are using people’s pronouns, or names, or referring to them correctly as well too because that rainbow sticker can just be a sticker if there’s not that education and that follow through with it.”

A 2021 report by Trans Pulse Canada on Indigenous transgender, Two-Spirit, and non-binary healthcare in the country found nearly one in five individuals don’t have a primary healthcare provider and just over half have unmet healthcare needs.

APTN News recently reported about two Indigenous transgender people’s struggles to receive care in Winnipeg. They highlighted a need for more education on how doctors should treat transgender patients.

The search for a trans-positive doctor is only made more difficult the further away you live from major cities due to lack of options, says Wu.

“[T]hese issues and these accessibility needs are only kind of exacerbated because there’s no financial support for trans folks seeking healthcare to be able to travel and those sorts of things.”

Dr. Shayne Reitmeier says that this was a barrier he noticed during his residency as a rural family physician in Manitoba’s southern health region, providing care to communities like Portage La Prairie, Sandy Bay First Nation and Long Plain First Nation.

“They feel isolated, they feel like there’s nobody that’s around them that can help them,” says Reitmeier. “A lot of people feel they can’t feel secure in themselves because how can they if the system doesn’t allow them to?”

Reitmeier says he decided to start a sexuality and gender program with the help of clinical pharmacist, Dr. Jamey Willsey, which offers gender-affirming healthcare services like hormone injection training to rural transgender, Two-Spirit and gender-diverse patients virtually and in-person.

The program also works as a consulting service for doctors who want to improve their scope of practice, with the hope that the program will eventually become “obsolete” as more doctors become comfortable doing the services themselves.

“We want people to just be able to seek out care wherever they are and be able to get gender-affirming services,” says Reitmeier, “but as a doctor who provides a lot of services as well, I do get that sometimes adding something to your belt is horrifying. And sometimes … that sense of like ‘I don’t know how to do this’ isn’t rooted in prejudice, although who are we kidding, it definitely is for lots of people too.

“But I mean sometimes it isn’t that, it’s just not feeling comfortable with a certain aspect.”

In our previous story, one transgender man was refused as a patient by a general practitioner who claimed to not know how to care for transgender patients.

APTN reached out to the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Manitoba to clarify when a physician may reject a patient due to transgender health needs.

“It is one thing to refer a patient to another physician who can provide more specialized care, but it is another to turn away a patient due to discrimination,” says the college. “If the care a patient requires is beyond the physician’s clinical competence, they must refer the patient to another registrant who will provide it.”

The general practitioner in question says he specializes in metabolic syndrome, but told the man that he could not monitor his hormone levels – a routine need for transgender people on hormone replacement therapy.

“Monitoring the hormone levels of anyone should be within the scope of a general practitioner. If complications arise – regardless if they are cisgender, transgender, or two-spirit folks- they should be referred to a specialist such as an endocrinologist” says the college, “endocrinologists specialize in Metabolic Syndrome”

Reitmeier says that although there is room for improvement in transgender healthcare, many doctors are stepping up to the plate.

“There are a lot more doctors out there, especially with our new training and new programs, that are willing to learn and actually want to adapt to the care needs of our community,” says Reitmeier, “I think that’s a positive shift we’re seeing in the culture that I don’t think a lot of members of the community are actually seeing because it’s not being vocalized and it’s not being celebrated”

Country-wide issue

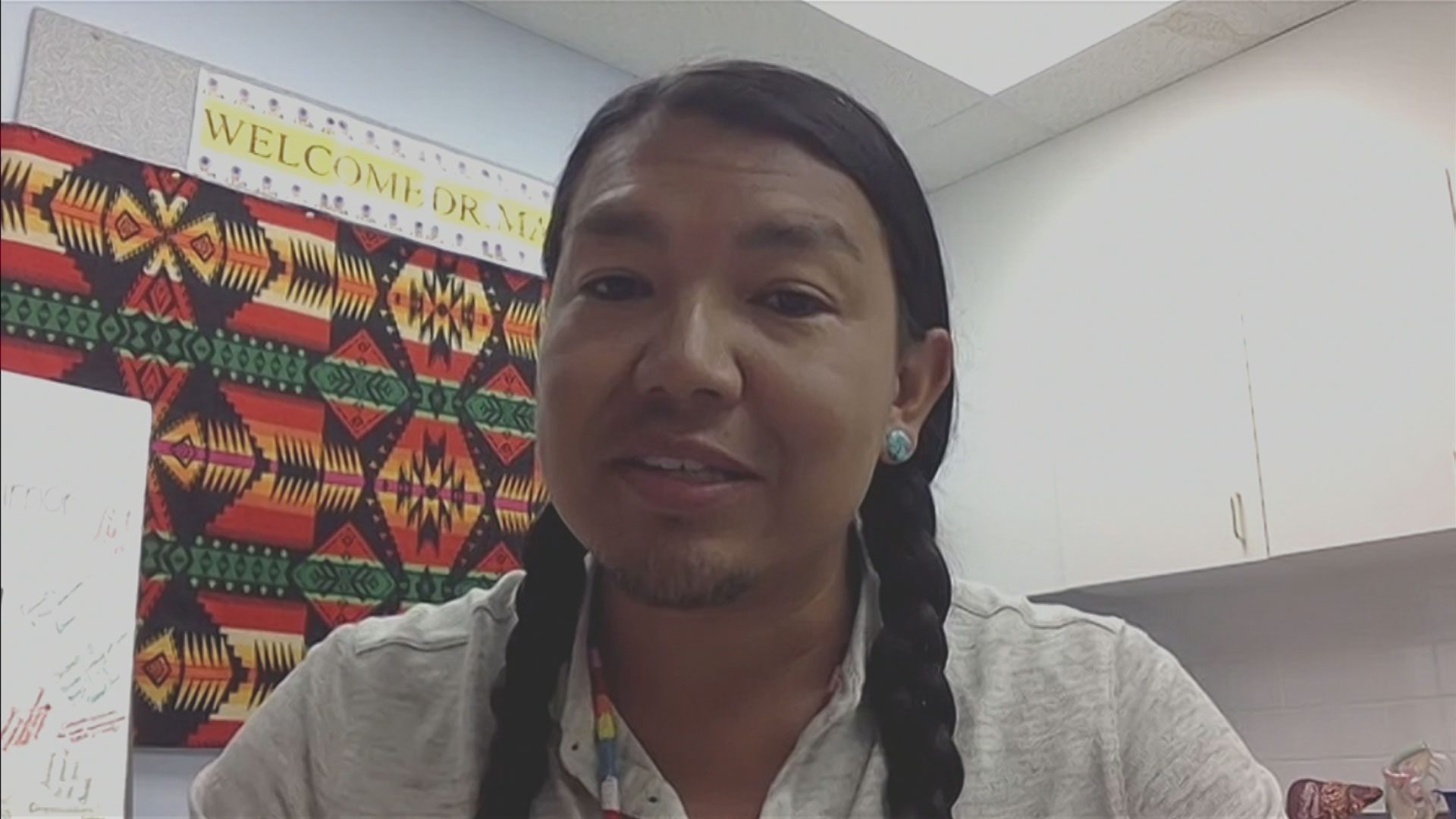

The need for more education isn’t only a problem in Manitoba but across the country, suggests Dr. James Makokis from Alberta.

The Cree, Two-Spirit doctor says he received only one hour of training on how to provide care to transgender people while in medical school.

During that time, they learned about general topics like what it means to be a transgender person but not much else.

“What we didn’t do or learn about was how to manage medical hormone replacement therapy, for example. Or to have examples of having a trans person as a normal part of our medical education. If a trans person comes in for an ear infection – how do you go about and treat that ear infection and you know, the ear just happens to be on somebody who is trans,” says Makokis.

Now a well-known advocate for safe healthcare for transgender and Two-Spirit people, Makokis makes it his mission to provide training to other physicians on how to do the same.

He says as part of his practice, he’s trained eight family physicians independently on how to treat patients. He says that transgender patients who are also marginalized in other ways, like being racialized or disabled, can have higher chances of experiencing discrimination.

“Definitely Indigenous people who are Two-Spirit or trans face the added barrier of racism within the healthcare system that continues to cause harm to them, and which prevents people from accessing care,” he says. “That fear of discrimination can have lasting health affects due to delays in receiving regular check-ups and preventative care.

“Trans men, for example, who still have cervixes need to have regular screening for cervical cancer. Because of their experience within the health-care system, they may forego having cervical cancer screenings and they may be more at risk for having advanced stages of diagnoses of cervical cancer. So, you can see how that affects somebody throughout their life,” says Dr. Makokis

He says with the wide range of resources available through organizations like the Canadian Professional Association for Transgender Health or even by consulting other colleagues already doing the work, he hopes more doctors will realize providing safe, gender-affirming care is within their scope of practice.

“I think that sometimes in physician practices, instead of reaching out to our colleagues, the easier thing for them is just saying ‘no, that I don’t know enough,’ and that’s not good enough of an answer,” says Makokis.