(A number of groups huddled at the Wabano Health Centre to talk about data and what it can do for communities. Photo: Tom Fennario/APTN)

One day, the early 21st century will likely be viewed as the industrial revolution of data.

Smartphones and the internet have made information abundant in ways never before seen.

Every day two and a half exabytes of data are produced – the equivalent of filling up 5 million laptops.

It’s a staggering amount.

The challenge is how to wrangle it all…and put it to good use.

“Using technology and data to save lives and improve the quality of life for our people, that’s where this is at, that’s what we’re talking about today,” said Assembly of First Nations Regional Chief for Ontario Isadore Day at Wednesday’s Indigenous controlled technology forum in Ottawa.

Day, a former addictions and mental health counselor, is excited by a new partnership with private industry to use financial, health and census data to tackle issues such as missing and murdered indigenous women and child abuse.

“With the government, and their approach up to this point, they have not been effective,” said Day.

Enter companies such as $4 billion (CAN) data analysis giant SAS. During a presentation, they explained how software is helping inform child welfare government entities about the support and services that would have the best outcomes for children in the social and family services system.

“If you get a home visit, you decrease the odds by 90 percent that there would be a tragic outcome,” said SAS Senior Director Greg Henderson said of their case study.

But because social services resources are limited, the trick is the how to know when a family could most use the visit of an intervention worker. SAS devised software that would let social workers know when there was a change in a child’s situation and be most likely to be put in imminent danger.

For instance, by having frequent updates on housing and criminal records, a social worker could receive an alert that a person who is dangerous has moved into the home of a vulnerable child.

It’s something that Henderson said might’ve save a child like Phoenix Sinclair.

“It was the boyfriend of the mother that ended up committing the murder, the challenge is that nobody knew that he was involved with the girl,” Henderson said.

This was despite the fact the boyfriend had a long history of domestic violence and that public records showed that he was living with Phoenix’s mother.

“Across the spectrum there were a number of data points out there could’ve tied this guy to this child and established an substantial risk that could have been investigated and potentially prevented this tragic outcome,” said Henderson.

Over the last three years, SAS has implemented similar technology in Los Angeles, North Carolina, and New Zealand.

Jennifer Lord of the Native Women’s Association of Canada said that while the implications are intriguing, she thinks many Indigenous people won’t necessarily embrace the idea of family and social services having so much access over their personal information.

“I don’t want, for example, our own children to be brought out and say they’re at risk for suicide, or for poverty, or poor housing,” said Lord. Rather, she said she’d rather data analytics focus less on risk factors and be used to determine more preventative solutions.

“The families suffering from poverty, or food insecurity, or poor housing conditions, maybe they don’t have access to parenting classes, we want that to be highlighted,” Lord said.

Isadore Day said this is all possible, but First Nations in Canada need what he calls “data sovereignty”.

“Why are we not building a process and another institutional layer of First Nations having control of their own information? I’m sure if we had something that was more suited and more in the hands and control of our First Nations, we would have much more First Nations people participating in our own censuses,” said Day.

But previous attempts at First Nations controlled data have been nixed by budget cuts and First Nations apathy towards information collecting endeavours like the census.

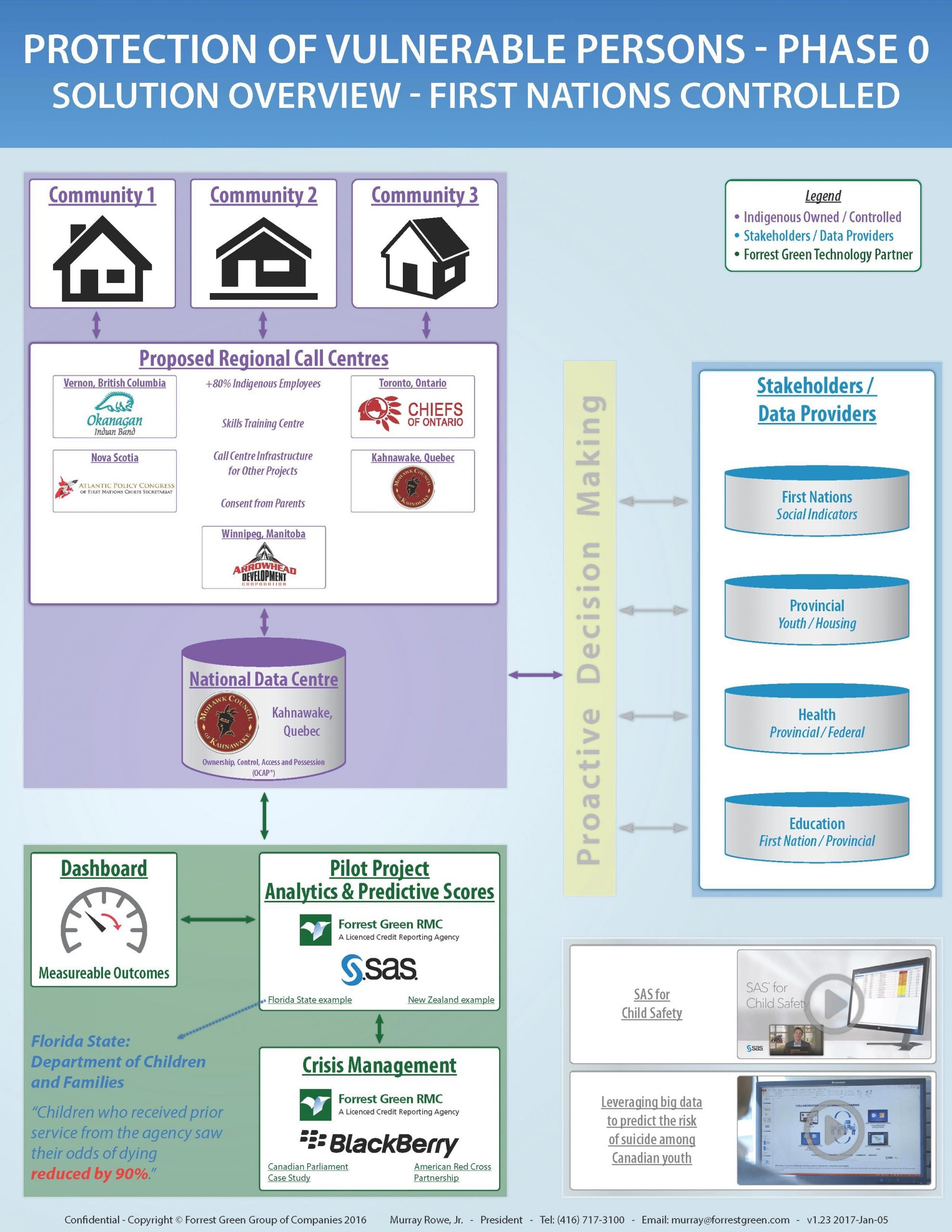

According to Murray Rowe, president of Indigenousdata.ca, one factor that holds back First Nations from controlling their own data is the federal government’s concerns over storage and privacy.

“We were asked by the chiefs of Ontario and other communities to make some recommendations with our partners, that being BlackBerry and SAS on how we could proactively assist communities,” Rowe said.

The solution is to have data funnel through government-certified secure BlackBerry technology to a Mohawk Internet Technologies data storage facility in Kahnawake Mohawk Territory near Montreal, where it will be accessible to SAS for analytics.

Kahnawake Grand Chief Joseph Tokwiro Norton summed up the end goal precisely during the conference.

“It’s now beyond just trying to make money…we’d like to make money too, but at the same time, let’s save lives,” said Norton.

Isadore Day said that he’s received a positive response from the federal government to discuss the possibility of having more control over First Nations data.

He also commits to consulting with Ontario First Nations people regarding their concerns over the use of their personal information.

“This has to be a community-based discussion as well,” said Day. “The better that our people are involved the more secure they’re going to feel and safer with us handling our information.”

Is this a way of improving the safety and security for children in care? Technology? no foot work for social workers ? Not that they do anyways. Hmm. I must have read it wrong somewhere.

Murray Rowe is also the president of Forest Green, RMC which includes contracts with the government and provinces. There is also members of the company who hold defence security clearance. That means they can take anything Rey have collected or any data and hand it over to the government without even notifying or asking for permission.