A photo of a truck at work at the Prairie Green Landfill near Winnipeg. Photo: Jesse Andrushko/APTN News

Searching a landfill in Manitoba for 30 days or more increases the success of finding human remains, says a confidential feasibility study obtained by APTN News.

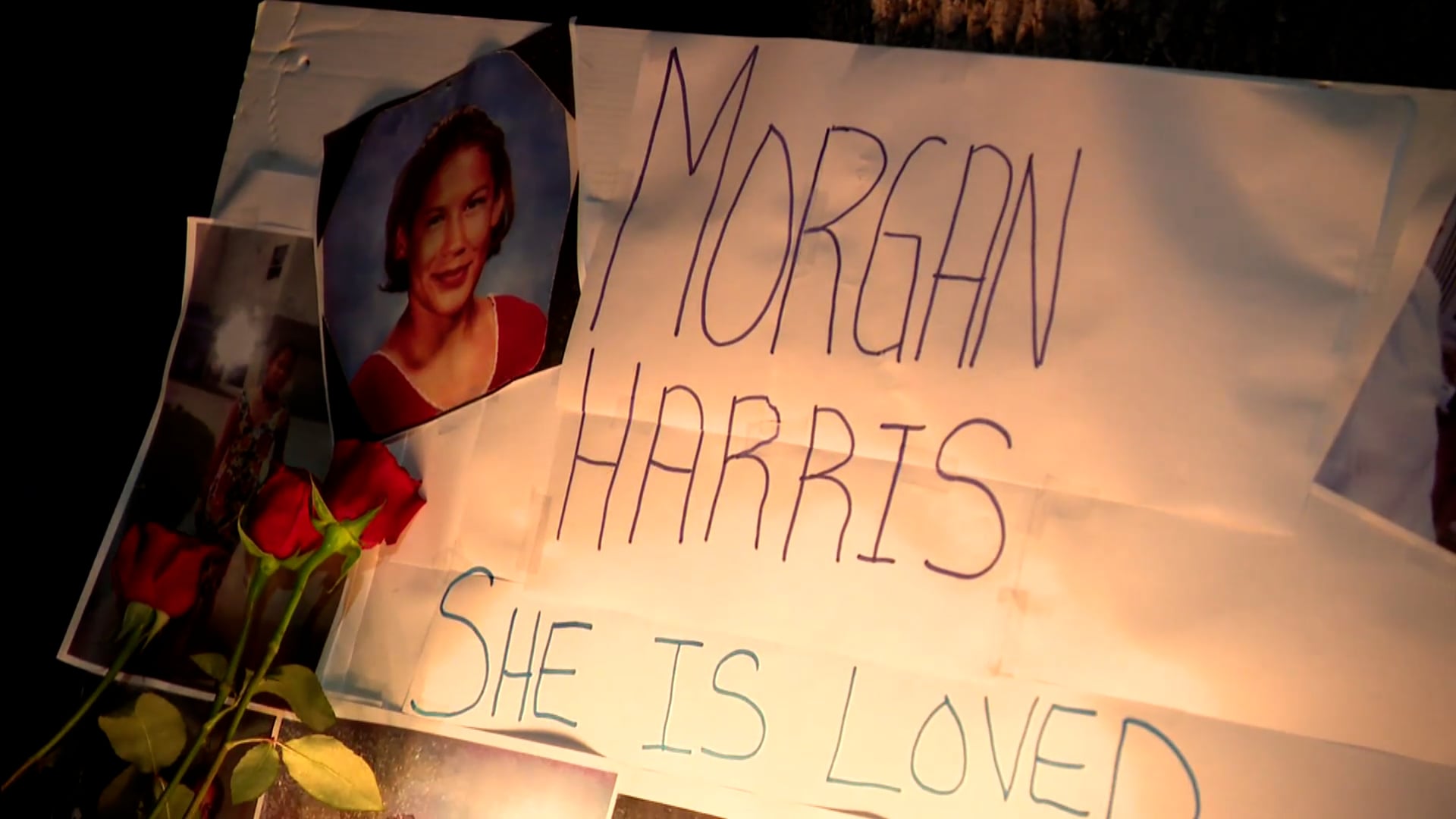

The finding is one of several in the 55-page study that supports a search “and humanitarian recovery” for the remains of Marcedes Myran and Morgan Harris, two First Nations women believed to have been slain by the same accused.

The recent study, funded with $500,000 from the federal government, was conducted by the Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs [AMC].

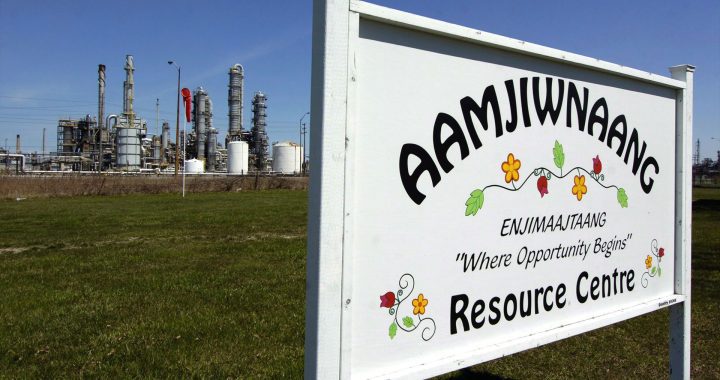

It was commissioned after the Winnipeg Police Service [WPS] refused to search for the women’s remains in nearby Prairie Green Landfill as part of their homicide investigation.

“The families of Morgan Harris and Marcedes Myran have been working relentlessly over the past couple of months to help us with the feasibility study,” the study said.

“They will do whatever is necessary to find their missing family members.”

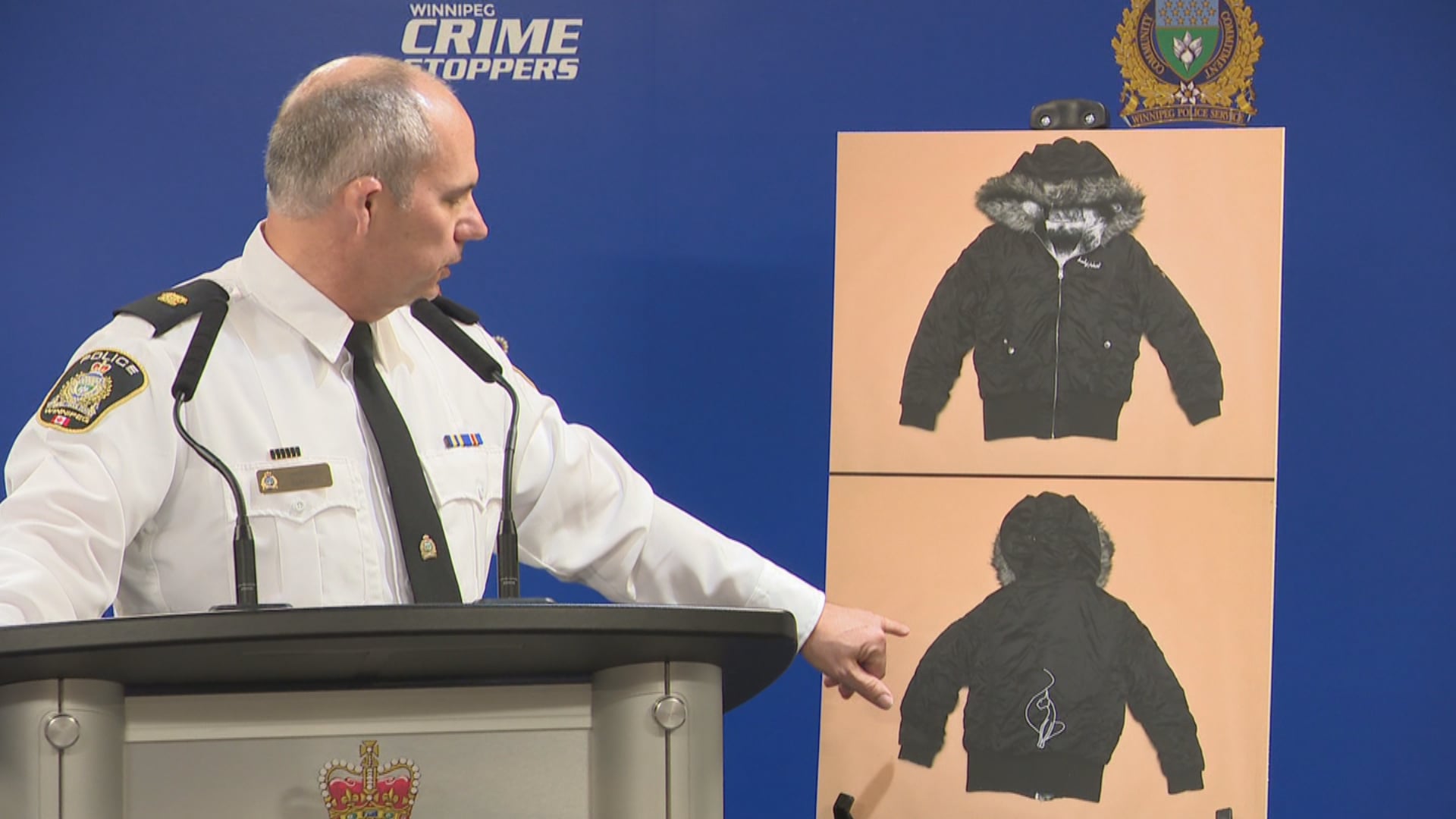

The WPS charged Jeremy Anthony Michael Skibicki, 35, with four counts of first-degree murder in December 2022. They allege he murdered and disposed of Myran, Harris, Rebecca Contois and an unidentified victim known as Buffalo Woman in city garbage dumpsters between March and May of 2022.

But WPS says it doesn’t need the remains of Myran and Harris to make their case, upsetting the victims’ families and angering AMC, which represents 62 of 63 First Nations in Manitoba.

“Although the WPS found physical and credible evidence, they cited, accompanied by a detailed PowerPoint (presentation), all the reasons they deemed a search and recovery impossible,” AMC said in the study.

“It is devastating to know that not only does [the accused] not value their daughters, but neither does the government.”

The WPS believes the womens’ remains were picked up as part of regular garbage collection and dumped at the privately owned Prairie Green [Myran and Harris] and city-owned Brady Road Landfill [Contois].

The remains of Buffalo Woman, who police are still trying to identify, have not been recovered.

The WPS and RCMP were represented on the committee that prepared the study, parts of which were first reported by The Canadian Press.

READ MORE: The case for searching the Prairie Green Landfill

The study lists the pros and cons of searching two “waste cells” or areas where Prairie Green says the garbage was dumped from that pickup point.

The landfill has 17 cells and accepts commercial and residential waste including asbestos and animal waste. The cells are about as long as a Canadian football field and as deep as an Olympic-sized swimming pool.

“Based on the location of the dumpster and the date and time it was picked up, it is believed that remains of both Marcedes and Morgan were likely in the same dumpster and the same garbage truck when deposited at the landfill,” said the study.

The cells were closed to further garbage as of June 20, 2022.

“To date, no additional material has been deposited in the same cells as that in which remains of Marcedes and Morgan are believed to be located,” said the study.

“Consequently, there are 34 days of material that have been deposited in the cell of interest since May 16, 2022.”

The study relies on three scholarly reports, including a survey of police officers who have worked on landfill searches, to conclude an assembly line search model would work best here. One of the American reports was published in the journal Forensic Archaeology in January 2019 after it reviewed 46 landfill searches in the U.S. between 1999 and 2009.

That is where a backhoe digs up covered and compacted garbage and a dump truck transports it to a search area. Once there, the garbage is fed into a hopper and distributed onto a conveyor belt where it is examined by searchers.

The study cited other cases where searches for bodies had been conducted at landfills.

“From a total of 46 cases, the average number of days searching that ended in the recovery of remains was slightly over 17 days,” the study quoted the research as claiming. “The longest search took 60 days, while the shortest lasted two hours.

“The success rate for the [46] surveyed cases was 43.5 per cent [20] while 30.4 per cent were unsuccessful. Success was unknown for 26.1 per cent due to incomplete or cessation of communication between the researchers and police agencies.”

The study says the assembly line process would take between 12 and 36 months and cost an estimated $84 million to $184 million. The money would be used to purchase the conveyor belt equipment, pay the loader and dump truck drivers, hire around-the-clock security and train searchers.

It would cover the costs of having forensic investigators on every shift, a forensic anthropologist on standby, emergency medical and hazmat personnel ready to treat possible exposure to flammable and toxic gases, and outfitting them all in personal protective equipment.

It would fund a necessary decontamination station and a contract with a forensic lab to test bones and other suspected remains.

The study further recommends beginning and ending each search day with a traditional First Nations ceremony. It also wants to see a building constructed or trailer rented for ceremonies and a place for First Nations elders and family members to gather.

The study does not say who should pay for the search.

But it does say this amount of money, time and labour does not guarantee a successful search.

“[We] have worked closely to consider a variety of potential methods of search and recovery, but no search comes with a guarantee,” the study said, recommending that mental health counsellors be available to help searchers, support staff and families deal with the “emotional costs.”

It estimates it would take up to six months to start the search and get approvals from provincial and federal health, safety and environmental agencies, which is important when it comes to the condition of the remains.

“At the 30-day mark between the victim entering the landfill and the start of a search, chances of a successful search are near even, but drop after a month has passed,” the study said.

“Searches lasting 30 days increase the success of locating human remains…Based on the results, [researchers] caution initiating a search when more than 60 days has passed between the body entering the landfill and the search being initiated.”

More than 60 days have passed here, but the study cites research on the decomposition of remains being “inhibited” by the soil or spray-material covering each layer of garbage. This restricts the effects of oxygen and scavenging animals.

“This process makes it possible to preserve human remains, although no research has suggested for how long,” the study added.

The study has not been released publicly but AMC held a news conference to speak to the media about it.

Further harm

AMC, in the study, said the refusal of the WPS to search for the remains was a form of systemic racism.

“This egregious treatment has caused a national crisis, moved the United Nations to action, the initiation of a Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls & Two-Spirit database, the creation of a counter exploitation unit, and the implementation of a variety of MMIG2S+ committees, including a landfill search feasibility study, all fulfilled and led by Firist Nation grassroots community members.”

The Native Womens’ Association of Canada and the National Family and Survivors Circle agreed.

They said in separate news releases that the WPS was causing further harm to the victims’ families, Indigenous women and the Indigenous community at large by refusing to conduct a search.

“These crimes are part of the genocide that was declared in 2019 by the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls – crimes that for too long have been discounted or given inadequate attention by police services across Canada,” NWAC said in a statement.

“…It is crucial for police forces to fulfill their obligations towards the 231 Calls for Justice from the Final Report of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls,” added the NFSC.

“In particular, Call for Justice 9.2i calls on all actors in the justice system, including police services, to “Review and revise all policies, practices, and procedures to ensure service delivery that is culturally appropriate and reflects no bias or racism toward Indigenous Peoples, including victims and survivors of violence.”

In its interim report, the Inquiry [2017-19] shared shocking statistics on the level of violence experienced by Indigenous women and girls, including that:

“Indigenous women are roughly seven times more likely than non-Indigenous women to be murdered by serial killers…[and] Indigenous women are physically assaulted, sexually assaulted or robbed almost three times as often as non-Indigenous women…Simply being Indigenous and female is a risk.”

Skibicki remains in custody and his trial is set for April 2024.