Community members in Aklavik are pointing to the effects on climate change for the delays in building an ice road that is critical to their daily lives in the winter.

“It’s a tough thing to try and predict because we’re not sure what’s going to happen, we know that the Earth’s climate is warming and it really affects our ways of life and how to get things done,” says the 27-year-old Gwich’in and Inuvialuk harvester-gatherer Jessi Pascal. “One of the big things that’s happening right now is the ice road.”

The winding 120 km seasonal Inuvik-Aklavik ice road along the Mackenzie River and its channels are normally open before Christmas and stays open normally until the end of April.

However, it just opened Jan 13 at its minimum weight capacity for cars and small pick-up trucks from construction delays after the Western Arctic region had December record-breaking levels of snow.

According to the 30 years of N.W.T government records, the latest the Inuvik-Aklavik ice road opened is Jan. 26 in 1998.

The Inuvik-Aklavik ice road isn’t the only N.W.T. ice road facing a delay this winter. While not an essential seasonal road, the Yellowknife-Dettah ice road is still not open, which often opens in December and has a latest-ever opening date of January 11.

Ice road delays from the warmer start to winter are being felt across Canada including at Cat Lake First Nation and Temagami First Nation in Northern Ontario and in northern Saskatchewan. In Eabametoong First Nation in Ontario, an early morning fire has destroyed the community’s school. According to the community, it’s waiting on two wildfire rapid attack trucks to arrive – but because of a delay in completing the winter road, the trucks haven’t been delivered. Ice road delays are also affecting Cat Lake First Nation in Northern Ontario.

Pascal is just starting up a weekly community radio show as Community Engagement Coordinator for the Wildlife Management Advisory Council North Slope. She and community members monitor existing climate change erosion slumping around the region.

-

Jessi Pascal as Community Engagement Coordinator for Wildlife Management Advisory Council North Slope hosting her second community radio show Jan 17th along with community guest Billy Storr, Mina McLeod’s father. Photo: Karli Zschogner/APTN.

This winter’s warmer weather and resulting higher amounts of snow are an added concern affecting the continual reliance of costly small plane food and mail delivery and personal transportation. Pascal says the delays have weighed on people’s mental and physical health from the restrictions she says, including the missing of month-long waiting lists for medical appointments because of transportation delays.

“Access is very important for our community,” she says. “We don’t have a bridge, we don’t have a highway or anything to connect us to goods like Inuvik, the closest place where we have access to like food that we can’t get here that don’t cost an arm and a leg.

“There’s been lot of shortages that were happening throughout the last couple of weeks. It stresses people out a little bit, especially when you want to host game nights, hanging out with friends…because there is no ice road, and it’s the only way to keep sane.”

The small airline North-Wright Airways that services the community charges around $400 round trip for the 20-minute flight. Pilots are often limited to Visual Flight Rules (VFR) which limits them to only flying in good weather.

“It’s quite pricey, and not everyone could afford that if you want to just get out for the weekend or get your mental state back in mind,” says Pascal.

Involved in multiple community boards, Mina McLeod agrees that there are added challenges and concerns.

“It’s harder when you have a longer break up or freeze up season because then we’re relying on planes and the planes rely on the weather,” she says. “It does create a lot of a lot of hardship, especially when they’re missing medical appointments because sometimes you’re waiting to see the doctor like specialists for months and then you finally get your appointment and then you missed it because the weather’s bad.”

She says making the Inuvik-Aklavik ice road has been generational. She manages her family’s contacting business, K & D Contracting, which along with water delivery and airport plowing, creates and plows the winter-spring vein of this ice road.

She works with the Government of the Northwest Territories (GNWT) Department of Infrastructure which authorizes and monitors the ice thickness with drilling augers and ground-penetrating radar.

“We’ve been doing the ice road now for about more than 15 years and we’ve always had it open before Christmas,” she says explaining this is their first year navigating an opening delay because of weather.

One of the reasons is that the Inuvik-Western Arctic region accumulated more snow in December from abnormally warm weather than any other year dating back to the early 1980s.

“[The Aklavik ice road] goes up to about 48,000 kilograms which is when or you can get the big trucks with all the building suppliers especially towards the end of the season,” she says explaining the thickness of about 4 ft for heavy trucks. “My pickup [truck] is 3,500 kilograms, so you can just only drive pickups and suburbans.”

Snow is an insulator, so not only does a larger amount prevent the ice from getting thicker, the added weight strains the ice creating overflow which is then difficult for plows.

“The river conditions changed so quickly, we actually sunk one of our plow trucks because it was so there was so much water and it just got stuck in the overflow. It’s a very challenging this year.”

Arctic is the fastest warming due to climate change accelerated by human emissions

-

Mina McLeod of Aklavik is Manager of family business K & C Contracting Ltd contracted by GNWT to make and plow the Inuvik-Aklavik Ice Road. She says her family has been making the ice road for generations. Photo: Karli Zschogner/APTN.

McLeod, also a chair of the local education council, says the unexpected amount of snow had affected kids’ routines, having to close school after the Christmas holidays for roof snow removal.

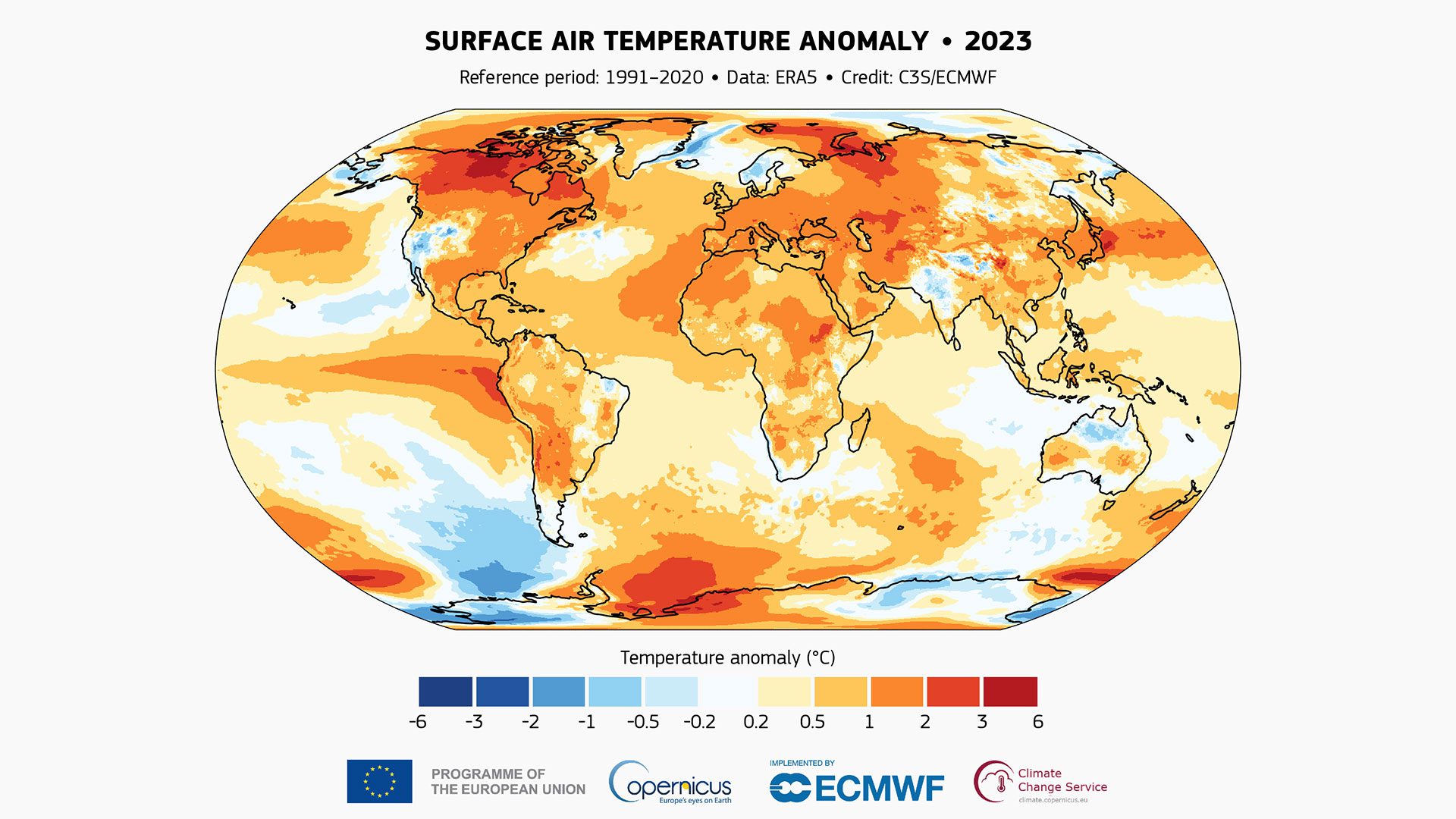

The realities of climate change are being felt across the world. Earlier this month the European Union’s Copernicus Climate Monitoring announced that 2023 was the hottest year on record – with global temperatures close to the 1.5 degree limit. according to their dataset, the global-average temperature for 2023 was 14.98°C, 0.17°C higher than recorded for last highest record in 2016.

“Northern Canada experienced some of the largest positive temperature anomalies worldwide in 2023, with annual mean temperatures 2 to 3°C above the average for the 1991-2020 reference period … including the area of interest, and more than 3°C in parts of the northwestern Territories and northeastern Nunavut,” says Muhammad Irfan on behalf of Copernicus Contracts and Press over email.

He also reiterates from their international data for December, overall Canada experiences warmer than average temperatures.

The year’s data includes monitoring of reducing Arctic sea ice.

“The significant sea ice loss in the Arctic leads to further warming as the ice-free ocean waters absorb, rather than reflect, incoming solar radiation, and also as melting ice absorbs more than solid ice. The clear decline in Arctic sea ice cover is thus contributing to amplifying the warming of the Arctic region,” says Irfan.

Last summer, southern N.W.T. experienced an unprecedented wildfire season which included evacuation of it’s capital city.

“The Arctic is one of the fastest warming areas in the globe,” says Nathan Gillett, a climate change expert for Environment and Climate Change Canada. “We look across Canada and we see warming trends everywhere, but those trends are strongest in the north.

“The intense warming that we’re seeing really is due to humans.” Gillett says he’s done years of research identifying human influence on temperature in the north including the impact on Arctic sea ice.”

Gillett says with the warming trends, the Arctic regions can expect overall warmer seasons, more snow and rain fall.

“How much more warming we see depends on, whether the globe is successful at reducing emissions, getting emissions down to zero,” he says. “If we get emissions to zero, we can expect to stabilize the climate as opposed to if we continue emitting, we’re going to see more and more warming.”

Community members want to see more government action

On Jan. 17, Aklavik experienced a fire at the government-run power plant. McLeod says if the volunteer fire department hadn’t been able to act quickly, the plant would have been lost.

‘It was a little scary because a lot of people, especially the people that live in housing, they don’t have woodstoves and they’re relying on power to run your furnace and boiler,’ she says. “We shut down the school immediately in case we needed that for emergency shelter because they have backup generators.

“If they were to have the fire kept going … they would have had to bring in generators and I don’t know how they would have got them in because our ice road isn’t thick enough yet and our runway isn’t long enough for a big plane … that would have been very serious.”

She says the fire remains an important wake up call for action including having more backup generators and a longer runway at the airport.

“We rely on ice roads, we rely on flights most of the year so they should make our airport longer, they should start thinking about if they can’t improve this one, then maybe we need to make a new one somewhere,” she says.

According to Northwright-Airways, Aklavik has a particularly small runway making it difficult or impossible to put land large airplanes like the twin-engine turbo-prop Beech 1900.

According to Northwright-Airways, Aklavik has a particularly small runway making it difficult or impossible to put larger airplanes like the twin engine turbo-prop Beech 1900 into there.

McLeod says adding to ice road delays is the inability to get their heavy equipment grader on the ice which helps to clear and thicken the ice.

“Usually they’re starting like the first or second week of January,” she says. “We need about 14,000 or 15,000 kilograms for the grader.”

Darren Campbell, a spokesperson for the territory’s Department of Infrastructure, says they did receive a formal request to extend the Aklavik airport runway during a February meeting with cabinet members including Frederick Blake Jr., former MLA for the Mackenzie Delta.

However, he says at this time there is no plan for the GNWT to extend the runway of the airport, as it currently can accommodate small-to-medium sized aircraft, which includes scheduled air carriers and medevac aircraft. Any significant runway extension at the Aklavik Airport would involve relocating the runway due to its proximity to the Peel River.

The spokesperson also responded that there are no current plans to construct year-round bridges for the Mackenzie and Peel River crossing along the Dempster Highway, which connects to the Yukon through seasonal ferries.

The department pointed to the construction of the Inuvik-to-Tuktoyaktuk Highway completed in 2017 and Tlicho Highway in 2021, and the proposed Mackenzie Valley Highway in efforts to address the warming climate in the North.

McLeod says adding to ice road delays is the inability to get their heavy equipment grader on the ice which helps to clear and thicken the ice.

“Usually they’re starting like the first or second week of January,” she says. “We need about 14,000 or 15,000 kilograms for the grader.”

Aklavik is a flooding risk

With this year’s amount of snow, Aklavik is bracing for expected flooding, which the territorial government monitors yearly as at-risk to flooding alongside eight other communities.

“We’re not in charge of nature and like how it will affect us,” says Pascal. “Having conversations with people, they haven’t seen this amount of snow in such a long time so that makes us kind of concerned about the springtime here.”

Aklavik, once a MacKenzie Delta hub, the hamlet of over 500, is no stranger to major flooding and erosion since the 1950s when the federal government urged relocation to its new model town of Inuvik, which many families stayed and rebuild.

“Flooding is not really something new to us, we’ve learned how to deal with it….and that’s why we say ‘Never Say Die.

“We have really good community leadership that can take charge and deal with things faster and we know what needs to be done,” says McLeod. “But I think the federal government and the territorial government, they have to kind of take direction from the local people.”

The Inuvik-Aklavik Ice Road normally stays open till end of April or early May.