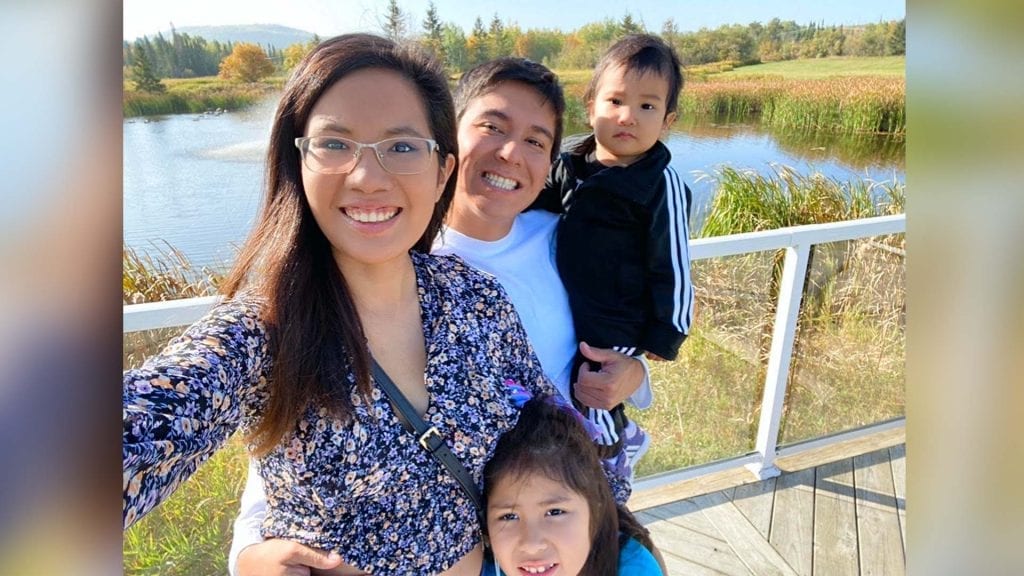

Autumn Windego with her partner, Tyler Medicine, and their children Vega Medicine and Layla Medicine. Rainy River First Nation band council has threatened Windego with banishment from the northwestern Ontario community. Submitted photo

Autumn Windego is still in her home.

And she has something to say.

“I will not stop advocating and I will always stand my ground and protect myself. I’m not just protecting myself; I’m protecting my babies,” said the Anishinaabe mother of two young girls on Nation to Nation.

“They shouldn’t have to be removed from their home and shouldn’t have to have their mother leave their home.”

Windego, 25, is talking about a letter that was hand delivered on Jan. 4, 2021. In it, chief and council of Rainy River First Nation (RRFN) threaten to exile her from the community.

Band manager Sonny McGinnis wrote he was serving Windego notice that chief and council would no longer tolerating her “continued attacks” against the community’s child protection team, known as the community care program.

And if Windego didn’t cut out these unspecified attacks, council would write up a band council resolution.

“Authorizing your immediate removal from our properties and lands of Rainy River First Nation,” wrote McGinnis, of the community located about 30 km west of Fort Frances, Ont.

“I trust you will heed this warning with the utmost seriousness and modify your behaviour and conduct accordingly.”

Windego says she’s never physically attacked anyone.

She also hasn’t attacked any buildings or cars.

She has, however, been an outspoken advocate on child welfare.

Windego has the lived experience having grown up as a Crown ward and used to working for the RRFN child protection team before quitting last summer.

She was also a source in several child welfare stories published by APTN News late last year.

Those stories focused, in part, on RRFN and Weechi-it-te-win Family Services, a licensed child welfare agency operating out of the former Fort Frances Indian Residential School.

Following some of those stories, the RRFN chief and council requested the Ontario government audit its child protection program, as well as conduct a financial review, to “identify deficiencies and efficiencies within the program,” according to band council meeting minutes posted on the RRFN’s website.

Details of both reviews are being still being ironed out.

RRFN is one of 10 First Nations operating under Weechi’s provincially-issued license.

Could Windego speaking out about the ongoing child welfare crisis in Treaty 3 be the considered an attack?

Chief and council won’t say, despite requests from N2N, and Windego’s lawyer, Douglas Judson.

Judson tried to answer that question when he appeared on N2N last week.

Windego felt it was safer to have Judson speak for her considering he had spent the last several weeks trying to clarify issues with chief and council behind the scenes.

But until now Windego says she was silenced by the banishment threat.

“I didn’t want to make any public posts on it because I didn’t want to be removed from my home,” said Windego.

She also thought of her daughters and not just because of what it would be like to see their mom removed from their home.

“I grew up in an urban setting, in a town, and I’m really trying to have my kids connected to their community because it is their grassroots. I didn’t want to do anything to jeopardize that,” said Windego, whose partner, Tyler Medicine, is a member of RRFN. Windego is from Siene River First Nation.

As she waited for council to clarify its position, which it never did, she grew more impatient.

“I still wanted to advocate,” she said, adding she has been working on a docu-series called Bring Our Children Home for several years. A trailer for the series can be found here.

But she didn’t feel safe doing so.

She also feared her kids might get apprehended.

Her anxiety would spike just going to the local Wal-Mart because she feared running into workers from the RRFN child protection team.

Now she doesn’t care about any of that.

There’s too much at stake.

“What I see wrong with the [child welfare] system is that kids are aging out of care and they don’t have their identity’s, they feel lost, families aren’t being reunited as common as they should, they are always being moved from home to home, siblings are being separated and have a lot parents who end up far more worse than where they were when the kids were apprehended,” said Windego.

Watch her full interview below.