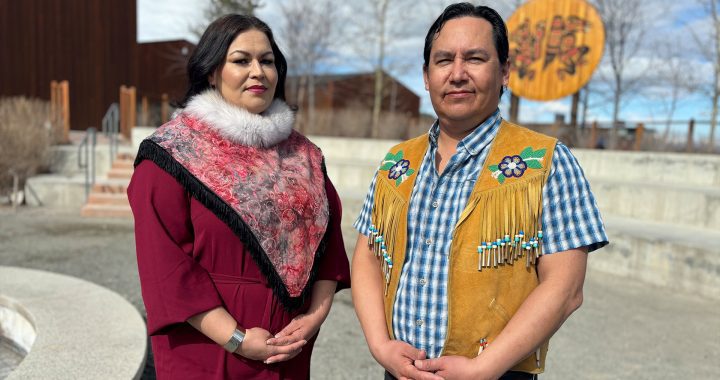

Leigh Joseph, whose ancestral name is Styawat, is an Sḵwx̱wú7mesh ethnobotanist using traditional knowledge to address Type 2 diabetes. Photo credit: Alana Paterson

Leigh Joseph steps outside of a noisy cafe to have a conversation about traditional plants, and returning to healthier diets. It’s a discussion that brings together threads of her work, research, personal life, and family history. Joseph, whose ancestral name is Styawat, is a Sḵwx̱wú7mesh ethnobotanist.

She uses Indigenous traditional knowledge to inform and teach communities how to revisit their relationships to carbohydrates, and reconnect with traditional diets.

“What I found in my research… there’s really an opportunity to specifically look at the role that plants can play in [the] Type 2 diabetes crisis and many communities,” Joseph says.

Diabetes rates are three to five times higher in Canadian Indigenous populations, than the general population, according to research published by the National Collaborating Centre for Indigenous Health (NCCIH).

“Indigenous people in Canada bear a disproportionate burden of diabetes,” the NCCIH research explains this is due to colonial impacts on socio-economic, political and cultural systems.

When it comes to Indigenous youth, eight in ten will develop T2D, as compared to five in ten non-Indigenous youth, according to the Canadian Journal of Diabetes.

As an ethnobotanist, Joseph researches the ways people and plants relate to each other. She has spent the last decade working on projects that link cultural knowledge and traditional diets to the health and wellness of Indigenous Peoples.

“Over the past two centuries, Indigenous Peoples in North America have undergone a significant change in traditional diet,” explains Joseph. She discusses the loss of working with medicinal plant use and an overall loss of way of life due to colonization.

“For many of our ancestors, good health, fitness and longevity were directly connected to their active lifestyles and traditional diets,” she says

Aside from teaching at Quest University and the University of Victoria, Joseph also facilitates hands-on workshops with Indigenous communities ranging from the Yukon to Saanich, Vancouver Island. These workshops cover topics including harvesting and utilizing traditional plant foods, medicines, wild harvest and cooking, salve making, tea blending, estuary root garden management, transplanting wild plants and preserving wild plants.

“When I have taught workshops on Vancouver Island, I have connected with the land and the communities in such a meaningful way,” says Joseph. “Collaborating with people from Indigenous communities brings a level of connectivity and a realization that we are all coming together to renew knowledge and practices that are so important to all of our families and communities.”

What did a traditional, pre-colonial diet look like?

Joseph describes coastal traditional diets as very high in marine and intertidal (or fish and shellfish) protein with special relationships to carbohydrates. Fibre would have been sourced through plants, and then roots of plants for the carbohydrates. She notes the special relationship people would have with plants of which they could only harvest roots once a year, and store for use throughout the year.

“Now we have a different relationship with carbohydrates being that they’re so, you know, kind of widely available. But in a traditional diet, they would have been a really specialized food that was really celebrated,” says Joseph. “Some communities did make flour out of cattail rhizomes. But really, carbohydrates were hard to come by. It would look like preserving this time of year. Berries, you’re drying and keeping very safe, or submerging them in oil or water in boxes. Drying seaweeds for the year.”

“One of the biggest changes,” Joseph says, “is our connection to the seasonality of our foods, along with that increase in access to carbohydrates, refined and processed sugars and fats.”

“You also can’t really separate out the impacts of residential school and other impacts of colonization in terms of how they can influence relationships with food and what it means to have access to food. And there’s of course an economic aspect to that as well.”

Joseph explains how there is a systemic impact of colonization underlying the health outcomes in Indigenous communities.

“Their systems, their connections to health, land, language,” says Joseph. “Everything that people draw strength from was attacked, actively.”

“I think celebrating the work and their resistance and their research and knowledge that’s happening now. And if I can play a role in that and, most importantly, in potentially inspiring Indigenous youth or other people who may want to take similar paths and see that’s really important.”

Finding our roots

Joseph’s interest in the relationship between food and culture developed at an early age.

“My childhood memories of time spent with my great aunt and uncle Chester and Eva Thomas at their property along the Nanaimo River really became central to me, ties me to what it means to connect with family and place and with health,” says Joseph, whose grandmother’s family is Snuneymuxw.

“Through sharing meals and harvesting food from the land that you’re spending time on. I’d helped my uncle hang fish in the smoke house. I really carry those with me in the work that I do in community.”

Many First Nations in the Vancouver Island area cultivated northern rice root in estuary gardens. Smaller rice-like bulblets were harvested, and the larger “grandmother” bulb was replanted. This food was an essential starch, often eaten with eulachon oil. Joseph has taken an active role in studying and practicing ecocultural restoration of these traditional cultivation practices.

“I learned from community members … just off the north end of Vancouver Island,” explains Joseph. “And in sharing conversations and learning around this plant, it became really apparent that although it’s considered a food plant, [it] so often equated as also medicine.”

“People that I was interviewing that were really focused on health and, specifically, the frequency and levels of Type 2 diabetes was also very top of mind,” she says. “As I started to work with other communities, I was also approached by some other researchers.”

Joseph explains how she began studying traditional plants’ potential, “addressing the management and prevention of Type 2 diabetes through increased access to plant foods and other traditional foods and medicine. … So I started working on that even before I started a PhD, but it became a central part of my research.”

She says she does this work in a culturally grounded way, which can be different for each community. She emulates an holistic approach in describing the broader impacts of these workshops and projects.

“Within those ancestral relationships with the land, there is health and wellness embedded in that. And I think that there’s a real opportunity for empowerment.”

“The levels of Type 2 diabetes and other chronic disease is directly linked to the impact of colonization. As we reclaim our health and our cultural practices that relate to health and wellness, this is an empowering act. It can be done in a complementary way with other health initiatives, but it can also be a very personal act to build a relationship with a plant that can help tend to your health.”

Rebuilding relationships with food

Discovering how to return to a traditional diet that is effective for those living with T2D can start with books and online resources, but Joseph also stresses the importance of focusing on the connection to land and plants.

“Rebuilding that connection, there’s really no substitute for starting to spend time observing plants. So that could be in a garden, along the trail, it could look like younger, more able-bodied people or family members bringing plants to Elders who have trouble getting outside and just really starting to interact with those plants.”

The next steps are in learning about a specific plant, gathering local knowledge and then finding ways to integrate it into diets. Although some foods need particular harvesting or preparation, there are many that are straightforward, additional nutrients that can be added to favourite recipes.

Joseph gives nettle as an example of an easy nutritive. “A lot of people utilize it as a medicine still, but that’s an excellent plant food. And it’s one that can be dried and ground up and used as a nutritional powder to add smoothies or soup,” she says.

“Finding ways to look at what it is that we can add in, as opposed to feeling like we need to take all of these things out, to make room for traditional foods. I think it’s really just starting with building that relationship, so making sure that you’re doing that safely.”

The significance in rebuilding relationships with traditional foods can be a guide in returning to a healthier diet, Joseph says.

“We are building a renewed sense of connection to the land and all that it offers to sustain us physically, spiritually and emotionally,” writes Joseph on her website, describing her PhD research.

“In this time of Indigenous Knowledge renewal and healing, we are looking to our ancestors for guidance as we move towards healing [through] connecting to our Traditional Knowledge.”