Note: This story contains racial slurs for Indigenous people.

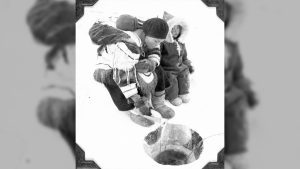

When Deborah Kigjugalik Webster’s mother, Sally Webster, spotted a photo of an unidentified Inuit woman ice fishing in a newspaper, she knew immediately who it was.

The photo, taken in 1952 between the Nunavut communities of Baker Lake and Chesterfield Inlet, shows a woman in an amauti, a parka typically worn by Inuit women, as well as a small child and an infant tucked into the woman’s amauti with its face turned away from the camera.

Webster instantly recognized the woman as her mother, Rhoda Qaqsauq, and the children as her two sisters, Janet Tagoona and Lucy Evo.

“My mom was very excited,” Kigjugalik Webster said. “She was very happy to see this image.”

The photo also happens to be one of 30 million housed at Library and Archives Canada (LAC), the federal institution responsible for acquiring and preserving Canada’s documentary heritage. While Kigjugalik Webster’s mother was able to identify her family members, most photographs of Indigenous people in LAC’s repositories remain unknown.

Beth Greenhorn, acting manager for LAC’s online content division, said few of the Indigenous people photographed were ever named.

For the last two decades, LAC has been appealing to the public to help it name those people.

It’s called Project Naming.

“Through digitization, we’re able to share and disseminate these photographs to a wide audience, and Canada is a huge, huge country,” Greenhorn said.

“Being able to provide someone’s sense of identity, I think it’s just a very important thing to do. It’s being respectful and it’s part of the work we’re doing towards reconciliation.”

Correcting past wrongs

Project Naming started in 2002 as a collaboration between LAC, the Nunavut government and the Nunavut Sivuniksavut training program for Inuit young people.

Initially focused on students bringing photographs back to remote Nunavut hamlets, its since expanded to include photographs of First Nations and Métis communities, as well as Inuit communities outside of Nunavut.

Anyone can browse its digital collection and contribute information about identification through an online form. High-resolution prints are provided for those who can identify relatives.

Greenhorn said around 2,500 people have been identified so far.

“Through Project Naming, what we’re trying to do is to correct these past wrongs by adding a name to a face and restoring a sense of dignity to that person,” she said.

‘A little mystery’

Kigjugalik Webster often encounters missing names in her work.

A researcher who works with LAC to help identify Inuit special constables, she said it isn’t uncommon for photos to be missing identification.

She points to one example of a photograph of an RCMP officer and two Inuit special constables. The RCMP officer is named; the two Inuit men in the photograph are not.

“By sharing these images, people can say ‘Oh, I recognize that man. This is his name,’” she said.

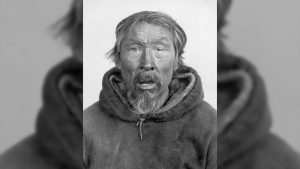

Others, like a 1926 photo of an Inuit special constable who was originally referred to as a native from Repulse Bay named Bye and Bye, were identified by English nicknames. According to LAC’s website, the man’s identity has since been updated to include his English name, Joseph Ugiaqut of Naujaat.

While not much is known about the man, Kigjugalik Webster was able to track down some information.

She said the historical record shows the man’s Inuktitut name was Siattiaq. He was given an English nickname by whalers working in the Nunavut community of Cape Fullerton.

“I love finding out names,” she said. “It’s kind of a little mystery, and then correcting them.”

‘Decolonizing the collection’

Many of the photographs of Indigenous people in LAC’s repositories date back to the 19th and early to mid-20th centuries. They serve as a stark reminder of Canada’s colonial attitude towards Indigenous people.

Most photographs come from federal agencies and private collections. Captions often describe those photographed as native, half-breed, Eskimo or squaw.

If given a name at all, they’re often misspelled, anglicized or simply inaccurate.

“Indigenous people were not identified partly because there was a language barrier,” Greenhorn said.

“I think at the time there was a prevailing attitude that Indigenous peoples would become assimilated into a dominant culture, and it wasn’t really important to keep their names.”

For Kigjugalik Webster, who is Inuit and grew up in Baker Lake, the absence of names of her people in historical photographs is a reminder of Canada’s painful past.

“Our Inuit names are part of our identity. It’s very important,” she said. “It’s disappointing actually to see that we were not seen as equals, we’re always second-class citizens.”

She feels the project’s focus on naming is an act of reconciliation.

“We’re decolonizing the collection. We’re saying here we are and our names are important to be included in the records for future generations to learn about.”

Power of social media

Since turning to Facebook in 2015, the project now has an even wider reach. Over 3,000 people follow its Facebook page, which posts unidentified photos regularly.

Greenhorn noted one of the first people to be identified through social media was a 1957 photo of an Indigenous man in Alberta driving a tractor.

Family members identified the man as Cecil Crowfoot, a member of the Siksika Nation and one of the original founders of the Aboriginal Multimedia Society and Windspeaker News.

During the first two weeks of December, the project’s team launched Finding Kin, an initiative where it partnered with the Anishinabek Nation by posting photos of different Treaty 9 communities that were part of its signing ceremonies in the early 20th century.

Greenhorn said the initiative was successful, increasing engagement on Facebook by around 800 per cent.

“This was an incredible example of the power of social media. It was amazing to reach a whole lot of people,” she said.

Unidentified photos of Mi’Kmaq communities will be featured in the coming months, she added.

The project also lead to the creation of a book, Atiqput: Inuit Oral History and Project Naming.

Published in 2022 and co-edited and co-written by Greenhorn, Kigjugalik Webster and other researchers, the book explores the importance of Inuit naming and the project’s history.

‘Part of our story’

For the thousands of Indigenous people that have been identified through Project Naming, most are still unknown.

Greenhorn said many Indigenous communities are unaware of the project and there’s still work to do in terms of outreach and engagement.

She’s hopeful all Indigenous people in LAC’s repositories will one day be identified.

“I believe that it’s important that everybody is identified and has a name,” she said.

As for Kigjugalik Webster, she wants the world to know the names of Canada’s original people.

“This is part of our story, that’s why it’s important to be told.”