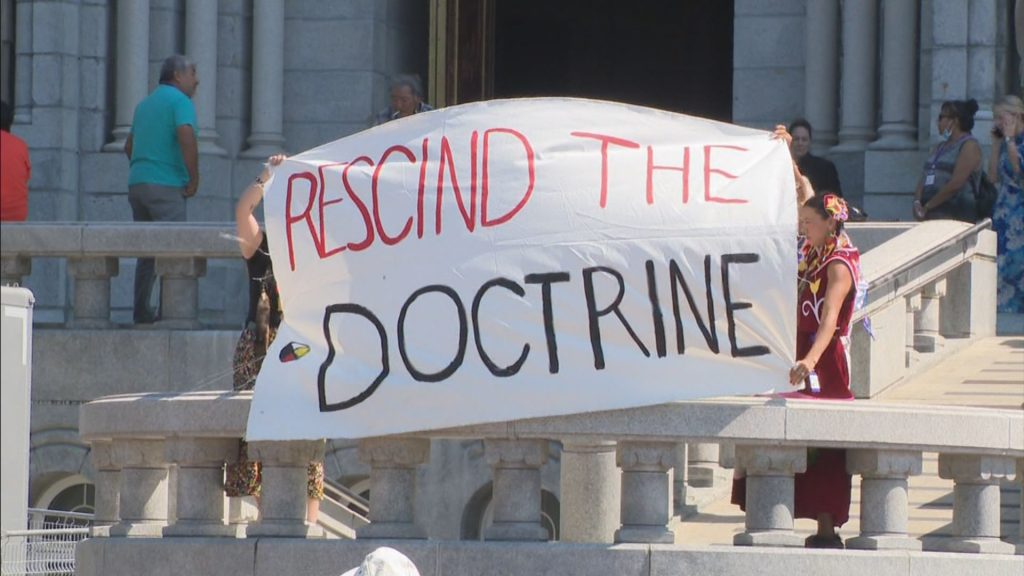

On the eve of the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation, Pam Palmater looks at the Doctrine of Discovery and opens up the discussion of what comes next.

After decades of advocacy by Indigenous Peoples worldwide, the Pope has finally repudiated the so-called “doctrine of discovery” and the immoral acts committed by colonial powers against Indigenous Peoples in its name.

Pope Francis went further by not only expressing his “strong support” for the implementation of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights and Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) but also condemned the use of any other concepts that don’t recognize the inherent human rights of Indigenous peoples.

“Never again can the Christian community allow itself to be infected by the idea that one culture is superior to others, or that it is legitimate to employ ways of coercing others,” he said.

Now that the Pope has repudiated the doctrine of discovery, what happens now?

The Pope may be the religious leader of the Holy See and ruler of the Vatican (sovereign city-state), but neither he nor those institutions have any decision-making powers or legal authority over Canada as a country, its Constitution, or any other laws in relation to Indigenous rights, lands, and sovereignty.

Canada’s common law is based on centuries of court decisions, laws, and governing practices that directly or indirectly use the doctrine as its foundation.

The idea that colonial and now Constitutional powers believe it had and continues to have a legal right to assert sovereignty over Indigenous lands, exploit Indigenous resources, control who is Indigenous and what rights we can exercise, is still very much a legal and political reality, backed up by state surveillance, impoverishment, brutalization, incarceration, and the killing of Indigenous Peoples, if necessary.

Canada also has a shameful history of breaching the rights of Indigenous Peoples at every turn. In fact, even the Supreme Court of Canada has acknowledged that Indigenous rights have been honoured more in the breach, than in the observance.

Winning a court case rarely equates to having Indigenous rights fully respected and implemented in a timely way, or at all.

Numerous reports, inquiries, and commissions have specifically recommended that the doctrine be repudiated because it not only lies at the heart of historic and ongoing genocide against Indigenous Peoples but also problematic court decisions that deny or limit our rights.

The 1996 Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (RCAP) explained that the doctrine is “at the heart of the modern doctrine of Aboriginal title, which holds that Aboriginal Peoples in North America do not ‘own’ their lands.”

In other words, it gave the “discovering” European nation the exclusive right to take the lands from Indigenous Peoples and significantly reduced Indigenous nations to mere occupants with limited rights. The RCAP commissioners called on Canada to abandon this outdated doctrine and renew the relationship based on a recognition of Indigenous nationhood, through a new Royal Proclamation that included the following:

Federal, provincial and territorial governments further the process of renewal by acknowledging that concepts such as terra nullius and the doctrine of discovery are factually, legally and morally wrong; declaring that such concepts no longer form part of law-making or policy development by Canadian governments; declaring that such concepts will not be the basis of arguments presented to the courts; committing themselves to renewal of the federation through consensual means to overcome the historical legacy of these concepts, which are impediments to Aboriginal people assuming their rightful place in the Canadian federation; and including a declaration to these ends in the new Royal Proclamation and its companion legislation.

The 2015 final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC) which studied Canada’s Indian residential school policy, also considered the doctrine of discovery and explained that although some European nations – like the English and French – rejected the papal bulls that supported Spanish and Portuguese colonial projects, they nevertheless maintained the principle – albeit in a modified way.

Instead of rejecting the principle outright, they argued that in order “To make the claim stick… it was necessary to discover lands and take possession of them.”

The TRC explained that this concept went on to become the foundation of American case law, starting with Johnson v. M’Intosh (1823), and was incorporated into Canadian case law.

Like RCAP, the TRC report also included a recommendation for Canada to create a new Royal Proclamation to advance meaningful reconciliation with Indigenous peoples. Call to Action #45 lays out a path forward that doesn’t include the doctrine:

45. We call upon the Government of Canada, on behalf of all Canadians, to jointly develop with Aboriginal peoples a Royal Proclamation of Reconciliation to be issued by the Crown. The proclamation would build on the Royal Proclamation of 1763 and the Treaty of Niagara of 1764, and reaffirm the nation-to-nation relationship between Aboriginal peoples and the Crown. The proclamation would include, but not be limited to, the following commitments:

i. Repudiate concepts used to justify European sovereignty over Indigenous lands and peoples such as the Doctrine of Discovery and terra nullius.

ii. Adopt and implement the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples as the framework for reconciliation.

iii. Renew or establish Treaty relationships based on principles of mutual recognition, mutual respect, and shared responsibility for maintaining those relationships into the future.

iv. Reconcile Aboriginal and Crown constitutional and legal orders to ensure that Aboriginal peoples are full partners in Confederation, including the recognition and integration of Indigenous laws and legal traditions in negotiation and implementation processes involving Treaties, land claims, and other constructive agreements.

The 2019 final report of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG) also took aim at the doctrine explaining that not only were European powers claiming Indigenous lands, but they also purported to claim souls for their God.

In the process, they subordinated, controlled, dominated, exploited, and vilified Indigenous women. Early explorers considered it their divine right and mission to claim Indigenous lands, while early missionaries attempted to “save” First Nation societies by changing their morals, values, beliefs, and relationships with women.

The MMIWG commissioners pointed out that there are numerous international human rights treaties, declarations, conventions, protocols and laws that specifically reject all doctrines based on cultural superiority.

While not directly calling for the repudiation of the doctrine, their key recommendations included calling on governments at all levels to immediately implement the recommendations from previous reports and commissions, including RCAP (Call for Justice 5.1) and the TRC (Call for Justice 5.21) – both of which called for its repudiation.

For anyone to argue that the repudiation is not significant would be ignoring decades of calls by Indigenous leaders, communities, political organizations and advocates for the Pope to do so.

This call was heard loud and clear when Pope Francis visited Canada to deliver his apology for residential schools in 2022. Many residential school survivors wanted and needed an apology as part of their healing journeys, and some survivors didn’t want the Pope to even come to Canada.

Just like some survivors and advocates will feel the Pope’s repudiation is meaningless, others welcome the change in direction.

No words can affect real change without corresponding action. Now, it is important to listen to the messaging that may come from Canadian leaders about where they stand on the repudiation.

While the repudiation itself is sorely lacking in full accountability and a commitment for reparations, the Pope does call on society to abandon “the colonizing mentality” inherent in the doctrine and walk a path where Indigenous rights are respected.

It is doubtful that repudiation alone will lead to immediate change, but if we put it into action, we may just forge a new path.

It is also possible that we will see lawyers making arguments before Canadian courts that seek to dismantle that colonizing mentality at the root of Canada’s laws and justice system.

In celebration of Bill C-15 becoming law, former federal Justice minister David Lametti explained that this legislation aimed to make the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) part of Canadian law.

He said that the doctrine has “no force whatsoever, no explanatory force, no legal force and no moral force” and went on to say that the doctrine needed to be specifically rejected and that UNDRIP effectively does that.

If Canada is serious about reconciliation, it will also walk beside us as we help change society for the better.

Canada’s problem is that is good at making promises, but not great at taking action to fulfill those promises. I would like to see Canada support the TRC’s recommendation and co-draft a Royal Proclamation on Reconciliation in partnership with Indigenous Peoples to specifically repudiate the doctrine of discovery, terra nullius and any other harmful doctrines and make sure this is done before the next election.

They should also undertake – in partnership with Indigenous rights holders and experts – a comprehensive review of laws and policies and ensure that they do not conflict with Indigenous rights generally and UNDRIP specifically. If they mean what they say, then they must be open, transparent, and accountable with a working plan and timelines to ensure this is completed before the next election.

Repudiation of the doctrine of discovery must not be at the symbolic level, to have meaning it must be given legal effect. Anything less simply preserves the status quo and the endless broken promises to Indigenous peoples about justice in our lifetime.

Pamela Palmater is a Mi’kmaw lawyer from Eel River Bar First Nation. She is also a professor and Chair in Indigenous Governance at Toronto Metropolitan University.