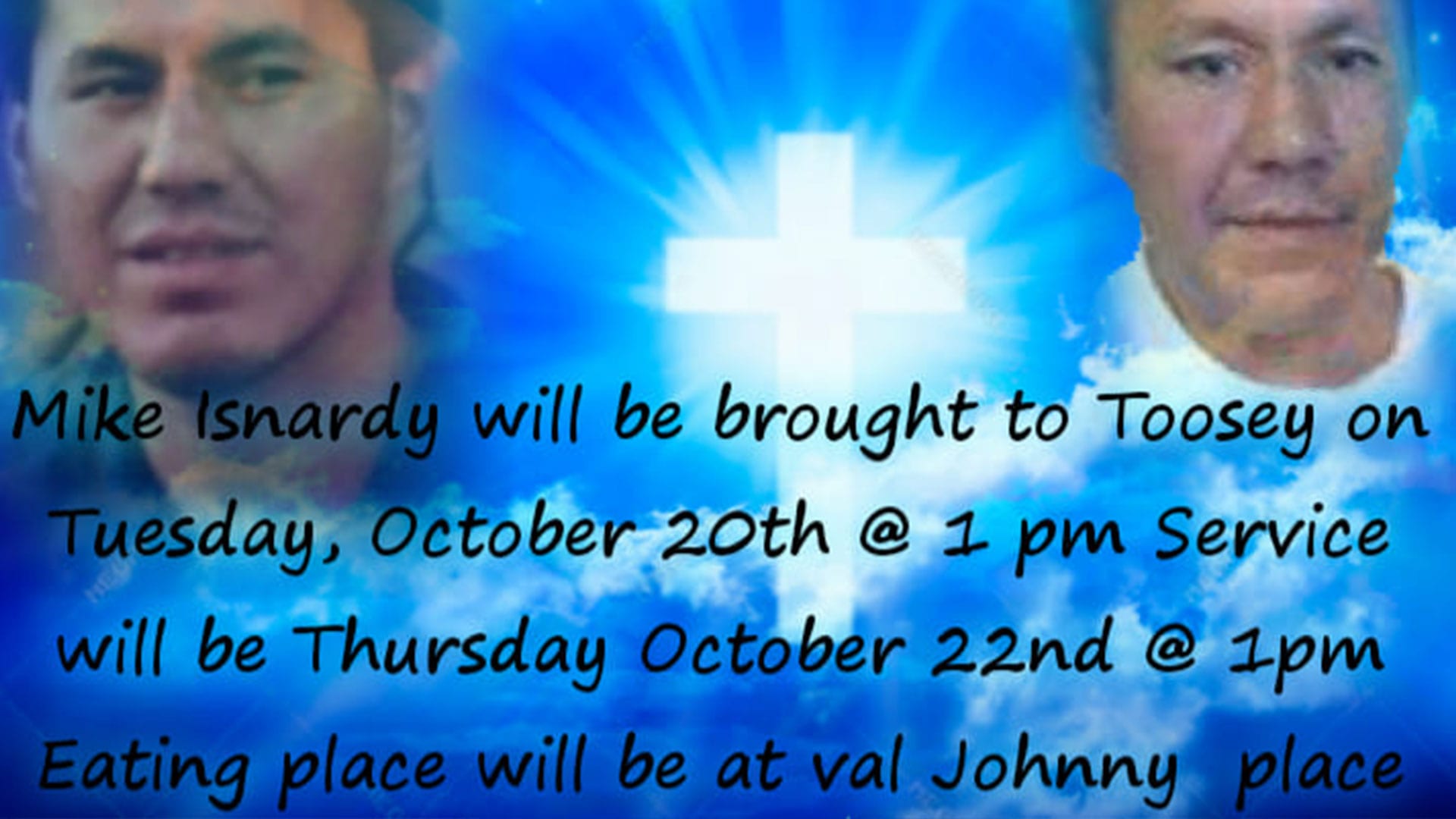

Mike Isnardy had to use a wheelchair after being arrested by the RCMP. Gloria Haines photo

Mike Isnardy was chatting with friends in downtown Williams Lake, B.C., when the police showed up.

It was October 2016 and the group was huddled against the wind until an RCMP constable ordered them out of the liquor store parking lot.

The group moved over. But it wasn’t enough.

The Mounties returned a second time, warning the pals to get going.

They did, according to Isnardy’s 2018 statement of claim against the RCMP in Williams Lake for assault.

But the cruiser with two officers came back. And that’s when members of the group scattered.

Isnardy, already hobbled by a bad back, was stopped and asked for ID.

“While the plaintiff was attempting to get his identification, Officer B grabbed him, put him in a chokehold and threw him against the back of a police car,” alleges the claim Isnardy filed against two unnamed constables and the B.C. government in 2018.

What happened next ruined his life and launched the lawsuit, his family says.

“During this altercation, both the plaintiff and Officer B fell to the ground. The plaintiff then tried to stand up at which point he was again grabbed by Officer B and this time choke-slam-style thrown to the ground with Officer B landing on top of him.”

The claim, which has not been tested in court, alleges an injured Isnardy was then handcuffed, put in the back of the car, and held for hours despite “repeated requests for medical assistance.”

It says the 45-year-old was “eventually” taken to hospital, where doctors diagnosed a broken back.

“The failure to secure proper and timely medical treatment for the Plaintiff resulted in the Plaintiff sustaining a spinal cord injury from what would have otherwise been a treatable fracture to his neck,” the claim alleges.

“The Defendants failed to provide the medical practitioners with the details of the Detention and the Takedown, which frustrated and delayed their ability to assist the Plaintiff.”

Isnardy would spend the rest of his life in a wheelchair, unable to feed or dress himself.

“It destroyed his and my sister’s life,” says his aunt, Illa Isnardy.

Mike’s “already hard life” became “harder,” agrees his half-sister Nadine Isnardy.

“He could not move to eat himself, drink himself; he could move his arm but not his fingers. They moved him around to Vancouver and Kamloops, and my mom was by his side those two, three years. Broke and homeless – staying in shelters – broke, but she stayed by his side.”

The RCMP, on that chilly October day, claim Mike was alone when they arrested him for public intoxication after receiving a complaint about a man lying in front of a restaurant.

In their statement of defence, they say he “was unable to provide a coherent response” and “interfering with the free use of the street and/or sidewalk” before the constable “placed the Plaintiff in handcuffs and assisted him into the back of a marked police vehicle.”

The arrest occurred without incident, the claim adds, and there was no second RCMP officer present or use of “excessive force” or “takedown.”

The RCMP deny Mike showed “any signs of significant distress”, reported “any significant pain or discomfort” or requested “medical assistance.”

They say they “immediately” transported him to local Cariboo Memorial Hospital after “he first reported difficulty breathing and swelling of his neck.”

They say officers passed along “all relevant information in the possession of the RCMP concerning their knowledge of the Plaintiffs condition.”

Nadine says Mike was homeless most of his adult life due to health and addiction issues, and after the arrest was living at Deni House, a personal care home next to the hospital.

His mother Kathleen Patrick, a member of Tl’esqox (Toosey) First Nation west of Williams Lake, stayed at a shelter in the central Interior city and visited him every day.

Mike’s claim for damages doesn’t include a dollar figure, but his aunt says he wanted enough money to get a wheelchair-accessible place with his mother.

Illa says he reunited with Patrick at age 25 after being raised by his grandmother in southern B.C.

“They were inseparable,” she says.

But Patrick died two years ago and Mike soon after – on Oct. 9, 2019 – of complications related to pneumonia.

That officially ended his lawsuit, unless a family member decides to pursue it.

Something Illa says is still up in the air.

Mike’s suit reminds them of the recent violent arrest of another Indigenous man by Mounties caught on video in the same central Interior city.

“I’ve seen (the viral video) on Facebook…the person that (allegedly) got beat up, I know him.”

Watch the recent arrest video here:

The video shows an RCMP officer trying to handcuff a suspect, who briefly fled on foot from his vehicle and down into a ditch. A second officer appears to kick and punch the suspect.

Illa says Indigenous people, whose communities dot the region around the town, don’t feel safe around police unless they’re with others.

“People are OK if you’re in groups. Not if you’re by yourself,” she says, like the male arrested in the recent video or Mike.

“They think that beating them up is going to straighten them up. It’s not going to straighten them up.”

Mike claims the RCMP’s actions were “callous and devoid of any sense or recognition that the Plaintiff was a human being and worthy of being treated with both dignity and respect.”

It also questions why he was allegedly roughed up and detained.

Read More:

Teen allegedly beaten by RCMP officers still suffers, mother says

APTN News coverage of Policing in Canada

But the Mounties say it was a legal arrest under the Liquor Control and Licensing Act after they found him “stumbling” towards the bus depot.

His lawyer, Scott Stanley of Vancouver, says Indigenous clients fear and distrust the RCMP. And, instead of seeing the lawsuits as a way of improving policing, he says the force pushes back.

“When they defend these claims they’re defending them like they’re trying to protect the Crown jewels,” he says. “Right from the investigation stage to the lawyers they retain, they are not about taking responsibility.

“They’re about resisting responsibility for as long as they possibly can.”