A joint investigation by Global News and APTN Investigates has found disturbing conditions inside Ontario’s group homes, a network of private and not-for-profit facilities meant to protect some of the province’s most vulnerable children.

There is a significantly high number of injuries, extensive use of physical restraints, and missing kids among private service providers, the investigation found.

Former residents and experts in child welfare paint a startling portrait of a system that lacks qualified staff and neglects and even mistreats some children who have experienced trauma or have complex mental health needs.

These revelations are drawn from interviews with more than 65 group home workers, youth, and child welfare experts and exclusive analysis of a database of more than 10,000 serious occurrence reports — obtained through freedom of information requests.

Also called SORs, the reports are submitted to the province by service providers such as children’s aid societies, group-home operators, and foster-care agencies. For example, SORs document when a child dies, is injured, goes missing, or is physically restrained.

Between June 2020 and May 2021, the Global/APTN investigation found there were over 1,000 reports of serious injuries and over 2,000 reports of physical restraints — despite the province’s 2017 pledge to “minimize” their use.

Over 12,000 kids, 17 years old or younger, were legally in the care of a children’s aid society at any given moment in 2019, according to the latest provincial data.

What happens inside these homes is not disclosed to the public, unlike inspections for long-term care or daycare centres, which are posted online.

Inspection reports from the Ministry of Children, Community and Social Services also found instances of children sleeping on soiled mattresses, lack access to basic dental or medical care or proper clothing.

Children’s services used when kids are facing abuse or neglect in the home or are too challenging for their parents to handle, are part of an ecosystem serving children in Ontario at a cost of $1.8 billion in 2020. Of the roughly 300 licensed group homes in Ontario, nearly half are run by private “for-profit” companies.

For some operators, each child in care provides a revenue stream and comes with a “price tag,” child welfare experts say.

“The money flows with [kids] but it doesn’t flow to them,” said Kiaras Gharabaghi, the dean of community services at Toronto Metropolitan University, formerly Ryerson University. “We’re talking about the private sector, we’re talking about generating profits, we’re talking about companies doing business through kids as commodities.”

He said the data highlights how the current child welfare system doesn’t focus on the “dignity and care” of young people.

“Right now … there is a young person in a group home somewhere who’s hungry and not allowed to get food,” Gharabaghi said.

“There are young people everywhere in the province who are moving today from one placement to another, with all of their belongings jammed into garbage bags.

“That’s fundamentally problematic.”

The average cost of a group home bed is $315 a day, according to Global News’ analysis of quarterly financial data that children’s aid societies submitted to the Ontario government. But for kids with more complex needs who require a one-on-one worker, that number can skyrocket to more than $1,200 a day, as in one instance uncovered by Global News/APTN.

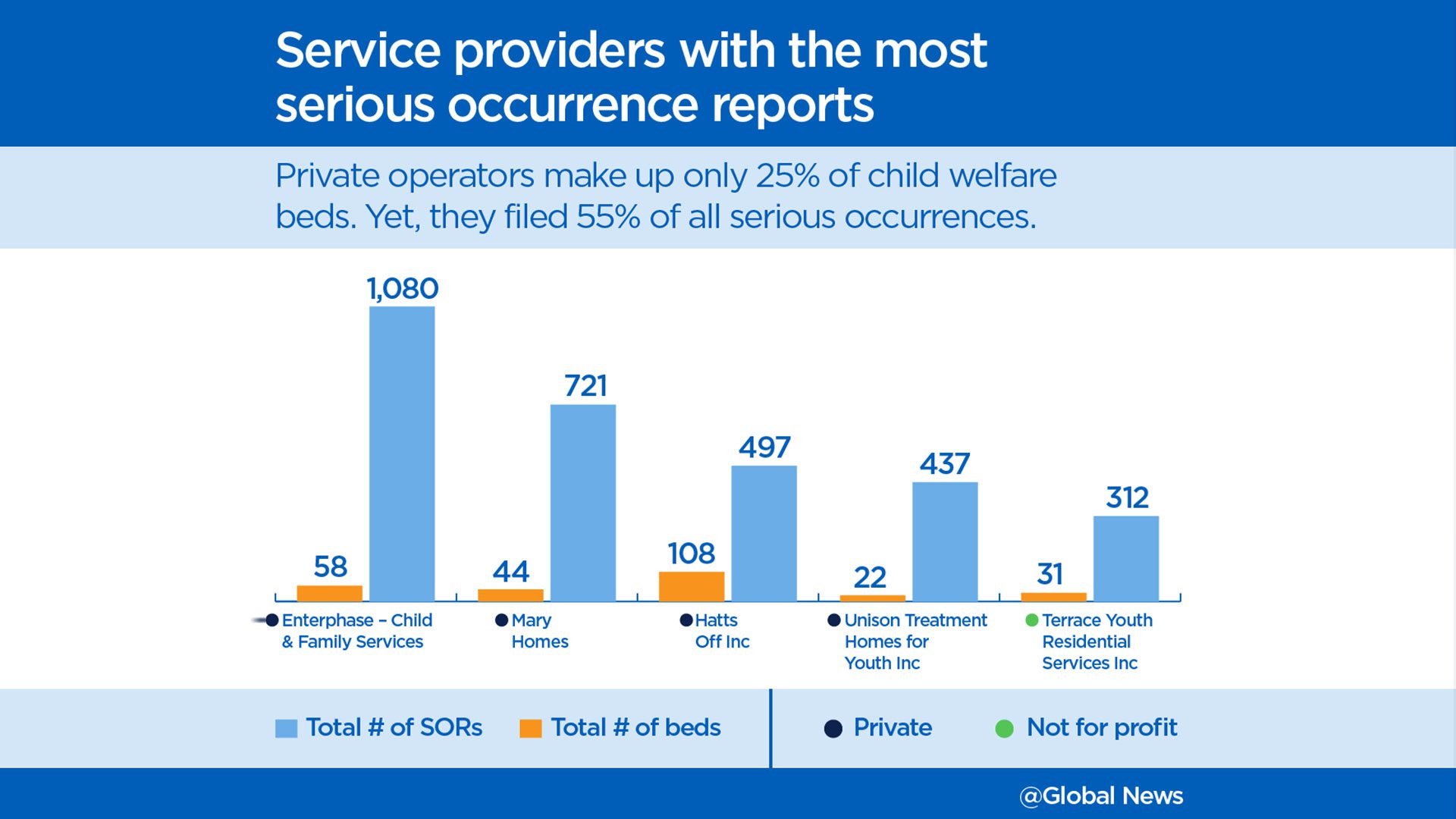

And while private operators make up only 25 per cent of beds across the province, they filed 55 per cent of all SORs at foster care and group homes, including 83 per cent of all physical restraints, 66 per cent of reports of missing youth, 62 per cent of medication errors, and 31 per cent of serious injuries.

Inside Mary Homes

Delana Land was reading the paranormal thriller What Lies Beneath in her bedroom one evening when a worker at Mary Homes told her to turn out the lights.

After pleading to continue reading, she says an argument ensued between her and staff, ending with a worker’s foot on her back.

“She ripped the book out of my hand and said I was resisting,” said Land, who was 15 at the time. “Eventually she stepped on my back and then I just kind of went down.”

Originally from Asubpeeschoseewagong First Nation, in northern Ontario, Land arrived at a Mary Homes’ residence in 2015, some 2,000 kilometres away from her home and family.

A private company, Mary Homes operates five group homes in the Ottawa area.

She said two workers physically restrained her before falling to the floor.

“I was probably on the floor for, like, 20 minutes,” she said. “They were very mean.”

For youth like Land, who have bounced from home to home inside the child welfare system, the experience can be terrifying.

“I tried opening my window, and I couldn’t. There were nails in the windows … because they thought we’d jump out,” said Land, now 21. She said shoes and jackets were locked up to prevent kids from running away.

“It was pretty scary.”

Residents who lived at Mary Homes said food was locked away and they lacked access to mental health support. They also said staff were poorly trained.

The 2020-2021 SOR data showed that Mary Homes had the highest number of serious injury reports in the province.

Unlike a home with foster parents, staff at Mary Homes work in shifts to supervise young people.

Land said the home was so bad she fled following the death of 13-year-old Amy Owen. She lived in a stairwell at the Rideau Centre Mall in Ottawa. In her view, it was better than living at Mary Homes.

“At least I was able to be me. I was able to be okay.”

Mary Homes declined repeated requests to comment on the allegations by former residents. The company also refused to comment on the data showing a high number of restraints inside their five group homes.

Effective last January, the Ministry of Children, Community and Social Services imposed conditions on Mary Homes’ group home licenses, including submitting an updated policy on the use of restraints, which employees would have to learn and adhere to. The ministry also instructed senior managers to follow up with staffers within 24 hours of an incident. If the manager discovers that an employee didn’t follow provincial regulations, the manager would have to file a report that would have to be kept on-site and available to ministry staff on request.

At the same time, the ministry also took aim at one of Delana Land’s former homes: workers were no longer allowed to lock up kids’ shoes.

A pattern of physical restraints

The data analyzed by Global News and APTN revealed a high number of incidents that involve physical restraints, which can include immobilizing a child by the shoulders and wrists with their arms extended, sometimes face-down on the ground.

While group homes account for only 20 per cent of the beds in the child welfare system, they account for 90 per cent of the reports for physical restraints in residential care.

Under provincial regulations, physical restraints are only supposed to be used when a child or youth poses an imminent risk of injury to themselves or others.

The three service providers that submitted the most SORs — Enterphase Child & Family Services, Mary Homes and Hatts Off Inc. — make up nearly a quarter of all SORs and 58 per cent of reports for physical restraints.

The 2020-2021 serious occurrence data also showed Mary Homes had the highest number of serious injury reports in the province.

“Restraints are considered therapeutic interventions. I think restraints are acts of violence,” Gharabaghi said. “Certainly, the young people will tell you that they’re experienced as acts of violence.”

“We have an official system, a publicly regulated system, in which institutional violence is considered normal and good.”

‘They’re choking me’

Jessica Fowler, originally from the Kingston area, was just four years old when she entered the child welfare system.

Separated from her sisters, she moved around the system 15 times, including instances where she said she was abused or was “starved.”

“There’s nothing I could do about my situation,” she said.

“It’s really scary when you’re in it because you don’t know where you’re going.”

She said the most violent experience was when she was 16 and arrived at a Mary Homes residence on the outskirts of Ottawa. She also lived at Mary Homes’ Wilhaven residence for a period of time.

Fowler said she was repeatedly humiliated, threatened and physically restrained by staff.

“[Staff] would go straight into a restraint instead of trying to de-escalate the situation,” she said, adding that employees would seldom try to speak calmly with kids first.

Sometimes, she said, a physical restraint would be used after something as minor as a disagreement over making a piece of toast at the wrong time.

“I was trying to make myself some breakfast,” she said. “I’m like, ‘My attitude is not going to change until I eat.’”

She said a staff member grabbed the toast out of her hand and started to drag her down the stairs.

“They were pulling on my shirt and choking me. They ripped my shirt and were kind of clawing at me to force me into my room,” she said.

“It’s scary. I’m being shoved down, like, a flight of stairs and they’re choking me, basically.”

For First Nations youth like Land, who are vastly overrepresented in care, the overuse of restraints is a continuation of intergenerational trauma, according to experts.

In Canada, only eight out of 100 children under the age of 14 are Indigenous, but they make up 52 per cent of children in foster care, according to federal data.

“Child welfare was built on the foundation of racism,” said Gharabaghi, who has spent more than four decades working in child welfare. “Thousands of children and youth are not getting what they need.

“I’m talking about catastrophic problems that have impacted entire demographic groups: Indigenous people, Black people in extraordinary ways.”

Amy Owen’s death

One of those young people who the system failed was Amy Owen. A teen from Poplar Hill First Nation, in northwestern Ontario, she lived at a Mary Homes residence with Land and Fowler.

Owen had repeatedly begged for help for mental health issues before taking her own life in April 2017, according to a $5.5-million lawsuit filed by her family.

A statement of claim filed by her father, Jeffrey Owen, states the family didn’t know which group home she was living in when she died.

“[Mary Homes] repeatedly ignored diagnosis events, obvious signs, and expert recommendations, which indicated that Amy was at serious risk of self-harm,” the lawsuit said.

A statement of defence, filed by Mary Homes, denied “all allegations of negligence” and said the company took “all efforts” to ensure her safety.

Owen and Land were close, like sisters, and had a pact to run away together, Land said.

“I kept telling her, we’re going to take off. She died on [April 17] and then I took off on the 20th,” she said. “I still did it because I knew she wanted it.”

Owen’s death traumatized some of the other kids in the Wilhaven home, which surrendered its licence in 2019.

Mary Homes isn’t the only company that frequently uses restraints.

Enterphase, a large operator of group homes in the Durham region outside of Toronto, operates five of the 10 children’s residences with the most SORs on a per-bed basis.

Cassandra Murphy, who worked at Enterphase from 2011 to 2014, said she was restraining children multiple times a day.

“Which to me might say, maybe this isn’t the right environment for them,” she said. “Maybe this home, this program, isn’t what they need to rehabilitate them. Maybe they need something different.”

Murphy, who completed a college diploma in correctional services, said she didn’t have the proper training to care for kids with complex mental health conditions.

Today, she lives with remorse.

“Having my own children now, there’s a lot of regrets on how I would have handled certain situations [differently] when I worked there,” she said.

“A lot of sadness for the children that were in those positions.”

With kids being restrained multiple times a day in some cases, she said a lack of mental health training contributed to a kind of “fight or flight mode” in workers that would often lead to restraints rather than de-escalation.

“[The data] shows our first response is to go hands-on with the child,” she said.

Physical restraints increasing in some cases

In April 2015, Justin Sangiuliano, a 17-year-old with a developmental disability, went into cardiac arrest and became unresponsive while being restrained, reportedly face-down and on the ground, at an Enterphase group home. He survived in hospital in a brain-dead state for five days.

The coroner found that an undiagnosed genetic mutation was the most important underlying cause of Sangiuliano’s sudden death. The restraint — and the struggle that preceded it — was a contributing factor, the coroner’s report said.

Enterphase’s executive director, Harold Cleary, said in a statement at the time that a Durham Children’s Aid Society investigation of the incident concluded that “there are no current child protection concerns that require ongoing involvement… staff administered (the physical restraint) appropriately.”

Following the fatal incident, government reports called for minimizing the practice of restraint but data obtained for this investigation shows that calls have gone unheeded.

In late 2015, the Toronto Star reported that Enterphase filed 152 SORs from January to mid-May 2015, 84 of which were for restraints — a rate of 1.8 restraints per bed.

New numbers for January to mid-May 2021 show Enterphase reported 213 restraints at a rate of 3.7 restraints per bed — double the rate from roughly seven years ago.

Enterphase declined a request for an on-camera interview.

Read More:

Death, deformities and Destruction: The truth about child welfare in northern Ontario

In a statement, a spokesperson for the group home operator said it prefers to “over-report” serious occurrences in the “interest of transparency.”

“Any time a caregiver redirects a child where there is physical contact, it is reported and identified as a restrictive intervention, and therefore deemed a restraint,” said Enterphase program manager Erica Stewart. “This includes situations where a staff member has held onto a child’s hand to prevent them from running onto a road and being struck by a vehicle.”

“At any given time, approximately 70% of the residents in our care are either suicidal or violent or both,” she said.

The company said its own records indicated that 40 per cent of restraints reported by Enterphase resulted in a child being placed on the ground in the “prone” position.

Stewart said that employees at Enterphase are required to have, at minimum, a post-secondary diploma and/or degree in a social services-related field.

“All new employees receive thorough and extensive training on the specific needs of the children in the home that they are working with,” she said.

The company also said it underwent an external review in 2020 and is implementing a restraint-reduction plan.

“Restraints are an emergency response used by a caregiver as a last resort after all other options have been exhausted in the event of immediate danger when someone is harming themselves or others,” Stewart said.

Other group home providers among the top five for the highest use of physical restraints on a per-bed basis were:

KidsKare Agency, out of Ottawa

Kushions Inc., in Barrie

Hand In Hand Children’s Services, based in the Peterborough area

KidsKare, Kushions, and Hand In Hand Children’s Services declined to respond to questions from Global News about the use of physical restraints.

Unison Treatment Homes, which had the highest overall number of SORs on a per-bed basis, said their policies forbid restraints. Instead, it attributed the frequency to a small number of youth who repeatedly ran away.

Of its 438 SORs, just over 400 involved missing-children reports — when kids are absent from a Unison home without permission.

“Three youth accounted for 58% of the SOR reports. Seven youth accounted for 89.5% of the SOR reports,” said Phillip Thibert, the company’s executive director. “These youth were considered by the police as being ‘chronic’ missing persons due to being [away without permission] from their placement.”

What needs to change?

Coura Niang, president of the Ontario Association of Child and Youth Care, said that there is not enough oversight of the child welfare system and that the current “framework” is not only doing damage to children now but also down the road.

“They don’t do as well as other children in early adulthood,” she said.

“The framework through which we’re caring is actually inconsistent, and that is what’s causing harm.”

For two decades, her association has been advocating that group-home workers be legally required to have a college or university degree in child and youth care.

“When you have an incredibly high instance of SORs, you need to look very closely because it can be an indicator that you have incorrectly, improperly trained practitioners who are inadvertently escalating behaviour,” Niang said.

“In the worst-case scenario today, we have front-line workers where the minimum qualification is that they have a driver’s licence and perhaps a high school diploma.”

There have been 11 government-funded reports over the last decade on the flaws in the child welfare system and how to fix them.

For example, a 2016 review of residential services co-authored by Gharabaghi included 33 recommendations, such as better inspections focused on quality of care, and “meaningful consequences” for service providers who don’t comply with provincial standards.

“Take the profit out of the system, take the price tag off kids,” Gharabaghi said. “That would revolutionize the way we care for people because it would render care a social process as opposed to an economic process.”

If it were to phase out for-profit service providers, Ontario would be following New Brunswick’s lead, where only not-for-profit organizations are eligible to be licensed.

Merrilee Fullerton, Ontario’s Minister of Children, Community and Social Services, declined a request to be interviewed about the state of the child welfare system.

In a statement, her office said physical restraints are “prohibited except in very specific circumstances” and “must never be used to punish a child or youth.”

After vowing to reform the system for years, Queen’s Park announced non-binding standards and a multi-year strategy to improve the child welfare system in July 2020.

In July 2023, new regulatory changes regarding restraints are scheduled to take effect. Homes whose policies allow their use will be required to tell children on arrival what the rules are regarding physical restraints.

Staff working in group homes will also need to have a degree, diploma or certificate in a relevant field or experience and skills relevant to their duties. The changes stop short of calling for a degree or diploma in child and youth care.

Under the new regulations, homes will be prohibited from using garbage bags to move children’s belongings between placements.

But with physical restraints still widely in use and inspection reports finding poor conditions in group homes, kids like Delana Land and Jessica Fowler want to see the system urgently transformed so another child doesn’t have to take the bed they left behind.

“It breaks my heart to think that there’s kids that are also going through the same things, that my bed was basically replaced with another kid who’s in the same situation that I was in,” Fowler said.

“I don’t want anyone else to experience the same things … feeling helpless and alone.”

With additional data analysis from Daniel Nass.