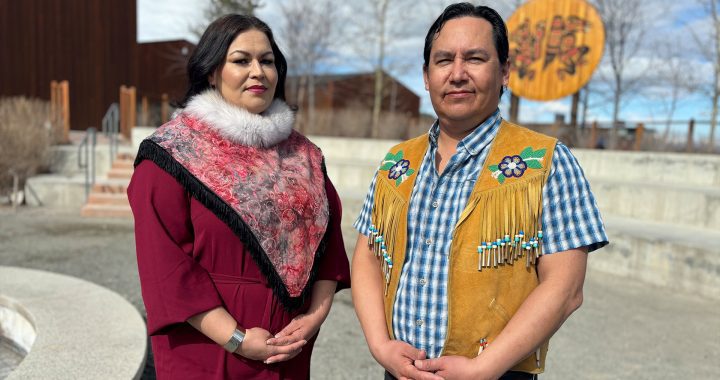

Ha’wilh Way’anis (Joshua Watts) says his latest art work connects people in contemporary time while using a traditional form. Photo courtesy: Joshua Watts.

Like his ancestors and mentors, Ha’wilh Way’anis’ (Joshua Watts) artistic practice carries messages, stories, and lessons through time.

Watts, Nuu-Chah-Nulth and Coast Salish from Port Alberni, Lake Cowichan and Squamish, says his work comes from thousands of years of practice, history and knowledge.

“Our people don’t have a term for ‘art’ in our traditional language,” Watts says. “Art is more than something to be hung on the wall. Our art carries a message and a history behind it.”

In his latest piece of work, Watts reflects on our current time of global pandemic, fear and darkness, and embeds a message of hope.

He says he wanted to connect people in our contemporary time, while invoking his traditional practice and form.

His two-dimensional design Eclipse represents the “swallowing of the moon,” he says, meant to emphasize how COVID-19 is “swallowing the world up.”

He connects a Nuu-chah-nulth oral history of an eclipse into the story of Eclipse.

“This painting depicts the Nuu-chah-nulth oral history of a great lingcod swallowing the moon during an eclipse. Back long ago, our people used to have a ceremony during the eclipse,” Watts explains. “They would sing so that the cod fish would spit the moon back out.”

Watts used the eclipse as a metaphor for COVID-19, which feels to him “like a year-long eclipse,” he says, and through ceremony and prayers, he hopes the world learns to make it through.

“I thought about how the experiences people are having today with the pandemic are similar to an eclipse,” Watts explains. “We would all stop what we are doing and have a ceremony to address what was going on. We would participate in a way of prayer and ceremony, to help us all get through.”

Watts started training in 2003, under Master Carver and Hereditary Chief ses siyam (Ray Natraoro) from the Squamish First Nation.

“I owe a lot to Ray and his generosity,” Watts says. “He shared everything — painting, carving, ceremony.”

Watts had the honour of learning from Beau Dick (Kwakwaka’wakw), his partner Linnea Dick’s late father and a legendary artist and leader on the west coast and beyond. He worked with Wayne Alfred (Kwakwaka’wakw) and Corey Bulpitt (Haida), as well as a non-Indigenous sculptor Linda Lindsay.

Connecting to contemporary times

A painting is meaningless without its context, the history, culture and people, says Watts.

“It has become common for people, especially non-Indigenous people, to consider the visual aspect of a piece of work, because that’s what is marketable” he explains.

“But what’s more important to us as Indigenous Peoples, as Nuu-chah-nulth, Salish Peoples, is what’s behind it — what’s thousands of years behind it.”

Watts tries to be “relevant” to the times with his work, he says, while also staying true to his traditional practices.

“People think our art is done, it’s history, it’s not relevant,” Watts says. “How can formline be relevant when you’re painting birds or animals, to peoples’ lives now? I’m exploring how to connect to people in contemporary time, using the traditional form.”

In his work, a moon is being swallowed, he explains, just as the world is being swallowed by this pandemic. But his message also carries hope, something he says his people have always had.

“You can still see the moon in the print, and that’s important, to not give up hope,” he explains. “My goal is to encourage people to think about what it will be like when we return to living our lives, without that fear.

“Song and ceremony has always been our way of getting through hardship, with that spiritual connection.”

Watts says he hopes his painting carries a positive note, reminding others to “stay strong” and “hold on to your traditions and ceremonies” during these trying times.

“It will get you through this,” he adds. After all, after darkness, there is always light.

Watts is currently working on a project with the Ts’uubaa-asatx First Nation in Lake Cowichan where he continues to breathe the teachings of his ancestors into the stories his art carries forward.