(Undated photo of child in body cast at Charles Camsell hospital in Alberta. Photo: NFB)

Brandi Morin

APTN National News

EDMONTON — It is known as one of the most haunted buildings in Alberta. The former Charles Camsell Hospital in Edmonton holds long forgotten secrets still waiting to come to light.

Freelance writer and Edmonton’s third historian laureate Danielle Metcalfe-Chenail has done extensive research about the history of the hospital.

Her blog is called the Ghosts of Camsell and focuses on unearthing the stories of the now abandoned building.

Metcalfe-Chenail first became interested in the history of Camsell while researching for her book Polar Winds: A Century of Flying the North when she learned of the tuberculosis x-ray tours of Indigenous communities.

“Some have said they’ve seen figures in the windows or have broken in and had weird things happen to them…,” she said. “There’s a lot of people I’ve talked to that think their ancestors spirits haven’t found peace and they’re still wandering. For a lot of people it was not a happy place.”

First established as a Jesuit College in the early 1900’s, it was then used as a military base for U.S. army soldiers building the Alaska highway in world war two and it eventually served as a hospital for service men with tuberculosis (TB) and other respiratory problems.

In 1946 the federal government turned it into an “Indian sanatorium” mainly for those suffering with TB.

TB was rampant and especially devastating to the Indigenous population in those days.

The government organized x-ray tours that sent planes to remote communities to screen for the disease. Across northern Canada and the prairies any found with symptoms were shipped to the Charles Camsell hospital for treatment between 1946 and 1966. This included men, women, children, babies.

Many of them never made it back home again.

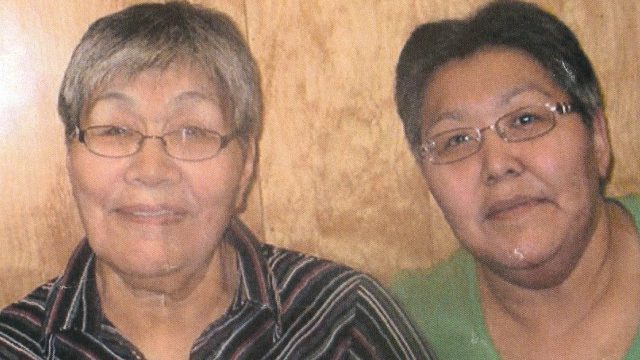

Louisa Baril, 72 of Cambridge Bay, Nunavut saw her father Joseph Eluik for the last time when she was 17.

Her mother had died when she was nine and her father raised her out on the land living in igloos, using dog teams and hunting for survival.

It was a good and happy life, she said.

Eluik lost the toes on both his feet during a sickness when he was a child and got by walking on his heels.

One day the medical planes came to town and doctors offered to help Eluik, who was by then in his late 40s, to get prosthetics for his feet.

He had never been on a plane or flown away from home before, but he thought it sounded like a good deal.

Eluik stayed on until the birth of his grandchild then left, having no idea where he would be taken.

“He told me he was going to leave,” said Baril. “When he was going to the airport he said he wanted to come back to see me, but the other people before him never came back so he didn’t know…he never came back.”

Baril found out from another man from Cambridge who was rooming with her father in the hospital that he had somehow got sick and passed away at Camsell.

“His roommate told me the night he (her father) was dying he was calling for me. When he stopped breathing he stopped calling me to him,” said Baril.

Baril and her family were never told what happened to her father or where or if he was buried.

Eluik’s granddaughter Cathy Aitaok has been searching for over a decade to locate her grandfather’s grave, hoping that her mother can one day find peace in finding out what happened to him.

Aitaok recently contacted Metcalfe-Chenail to see if she could find her grandfather.

In her research, Metcalfe-Chenail discovered that some of the former patients of the hospital were buried about 20 km away at the former Indian residential school in St. Albert, Alta.

Between 1946 and 1996, the cemetery was cared for by children attending the residential school.

Then the school closed in 1968 and Poundmakers treatment lodge located adjacent to the property took over the upkeep.

Eventually the cemetery was transferred to the City of Edmonton and was soon overrun by weeds and overgrown grass. Later a brush fire broke out that destroyed the grave markers.

Approximately 20 years ago, the city funded the building of a cairn with the engraved names of 98 patients of Camsell buried there.

Eluik’s name wasn’t listed.

Metcalfe-Chenail said that’s only where the Protestants and Anglicans were buried.

The Catholics, she said, are buried elsewhere and she is researching their location.

“The records are so tricky to track down. When people did pass away sometimes they didn’t try to contact family members, often they just couldn’t get a hold of them,” said Metcalfe-Chenail. “But they made such efforts to go to communities and get them out to bring them down here but they didn’t make the same efforts to ring them home again for burials.”

Some were lucky.

Ann Hardy, 58, of Edmonton was sent to the hospital when she was 10 and stayed there four months.

She was flown from Fort Smith, NWT after it was discovered she was developing TB. She said at first she was excited about the idea of going away, riding on a plane for the first time and that it felt like an adventure.

But her parents were very worried. Both of them had grown up in residential school and were very protective of their children and leery of the outside world.

Her mother came with her and stayed a few days in a nearby hotel and didn’t share Hardy’s enthusiasm.

“She was very tortured by the whole thing, very emotional, very upset,” said Hardy. “I really didn’t understand it at the time.”

Once arriving at the hospital Hardy realized how serious the situation was.

Soon, her mother had to go back home but made arrangements with hospital staff to let her daughter call home collect whenever she requested. It was an emotional goodbye, but Hardy said she soon got a roommate and was able to make friends.

Things weren’t entirely bad, she said. There was a playground area on the children’s ward where they were sometimes allowed to exercise and she holds fond memories of a day trip they took to the zoo.

These types of experiences were helpful in curbing some of the loneliness she felt.

“Depending on the nurse that was working it depended on how well our treatment was. We certainly didn’t get the outright abuse they got in the residential schools, but bearing in mind that we were so far away from home and away from our parents we certainly weren’t treated with the compassion I would want children treated with.”

She witnessed a young boy at the hospital immobilized by a body cast which was a typical treatment procedure for TB and it terrified her.

“They opened his lungs and scraped out the TB. All I knew is he had to be in the body cast for a year. To me that was torture. It was very difficult for him and he was very weak when he came out of the cast.”

Then one evening staff informed her they would perform the same lung surgery on her the next day.

“I got hysterically upset and called my parents. They didn’t know anything about it. They asked for the procedure to be halted.”

Her father flew to Edmonton and had a confrontation with the doctors, something that took Hardy by surprise because she said her father was fairly docile after his experiences in residential schools.

“The doctor told him ‘You’re ruining your daughter’s life and I won’t be responsible for this.’ My father said, ‘No, I don’t want you to do this to her,” said Hardy.

She was discharged early and sent home with “horse pills” medicine and the TB never again manifested throughout her lifetime.

Though thought of what if still lingers to this day,

“I just can’t imagine. It runs cold fear through me.”

Medical experiments.

It is rumoured that horrific medical procedures were carried out at Camsell that included shock treatments, nutritional experiments and sterilization further adding fuel to the notion of the building’s haunting.

Metcalfe-Chenail said the stories of what happened at Indian hospitals and the treatment of Aboriginal people there have been lost, however she believes acknowledging their existence is an important part of truth and reconciliation.

“It goes back to what Justice Murray Sinclair was saying. We’ve got to have a full picture and reconciliation doesn’t happen until you see the origins of some of those policies and some of the experiences for some of those people. And then you can show more compassion when creating new policies and we can work for better relationships and partnerships so that this kind of stuff doesn’t happen again.”

The original Camsell Indian hospital was torn down and rebuilt in the late 1960s as a provincial hospital where it operated until the late 1990s.

It has been abandoned ever since.

A developer recently bought the property which sits in the residential neighbourhood of Inglewood in Edmonton. The company is working on removing asbestos from the building with goals of eventually turning it into a 230 unit residential condominium project.

However, Metcalfe-Chenail would like to one day see a healing center and public art installed on the site to honour those who suffered there.

In the meantime Baril will keep searching for her father in the hopes of one day bringing him back home.

“He died in the wintertime. He was a good hunter… In the Spring I used to go look for him on the land and think he was gonna come home from hunting. When I’m really missing him I search for him in the distance,” said Baril.

OMG shock trement that is terrible i am so against that who could go through that 🙁 HATE IT