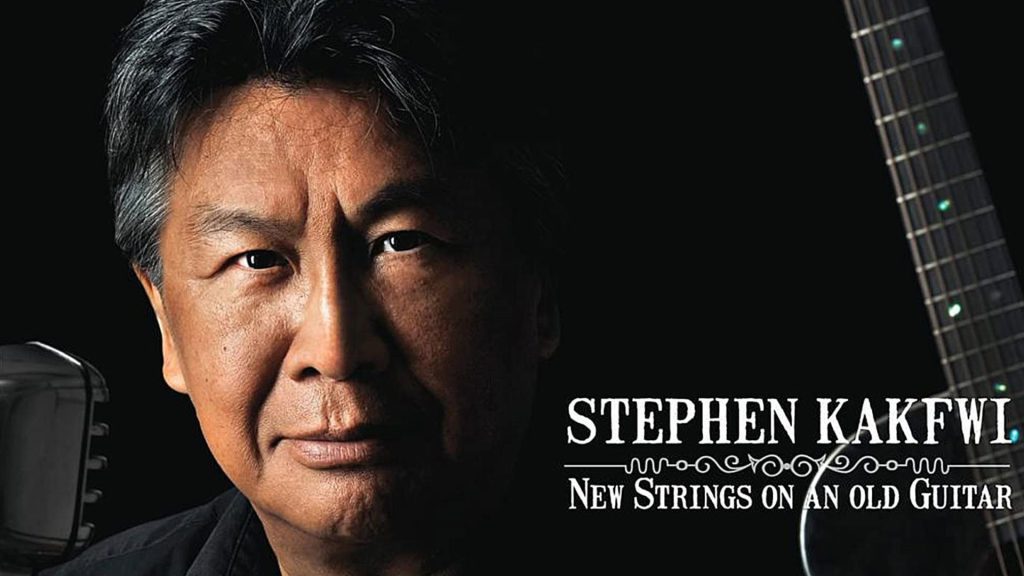

Former premier of N.W.T. pens memoir. Photo: Amazon website

Stephen Kakfwi says one of his proudest accomplishments has been overcoming the inability to feel any emotions after leaving residential school.

“I grew very limited in feeling joy, feeling happy and also feeling sad. Everything got flattened,” he said. “Overcoming that took years.”

The former Northwest Territories premier said he felt lucky when he met his wife, former journalist and Truth and Reconciliation commissioner Marie Wilson, in 1976.

“I felt she was like my prism,” he said. “She brought out all the colours of the world more than anybody I knew. She enjoyed things that I thought were just mundane.”

In his new memoir, “Stoneface: A Defiant Dene,” Kakfwi recounts his life starting from when he was three years old, including his experiences at residential school, the effect of tuberculosis on his family and his political career in the Northwest Territories.

“The book is in a way a celebration,” he said. “A lot of things happened to me, not all of them were good, but I worked hard for everything that’s good.”

Bush camp

Born in 1950 in a bush camp near Fort Good Hope, N.W.T., Kakfwi was sent to residential school at a young age, where he said he was sexually and physically abused. He went on to become an activist, politician and musician, serving as president of the Dene Nation from 1983 to 1987 before he was elected to the territorial legislature where he served in cabinet for 16 years, including as premier from 2000 to 2003.

Kakfwi said his book’s title comes from a nickname he was given by Nellie Cournoyea, who was the territory’s first female premier from 1992 to 1995, when they both served in cabinet.

“It kind of stuck with some of the other ministers,” he said. “(They) would say, ‘We can’t read you, you’re a hard person to read.’ I kind of liked that, I liked my persona.”

“When I finished my political career in December of 2003, you know I walked out of the legislature, I felt nothing,” he added. “It was as if I had walked out of a warehouse.”

Kakfwi said the title also reflects how he was affected by the abuse he endured at residential school. He said his memoir is the first time he’s written about those experiences in detail.

“I went back over everything and I actually relived everything,” he said. “It’s not a natural thing, it’s like asking somebody to go back to that time you had your worst toothache and tell me how you felt that time.”

Residential school

While that has been painful, Kakfwi said he wanted to respond to Canadians who question why Indigenous people don’t “get over” residential school. He said talking about what happened also helps.

“I was nine years old when I was sexually abused. I hold it in my head and my heart,” he said. “Today I’m 72 and it’s still with me, it’s not going to leave me and it’s kind of in my blood, you would say.”

Kakfwi said every lawyer, judge and teacher in Canada should read books like his to learn about the experiences of Indigenous people.

“We still have a long ways to go,” he said. “It is as if for a huge part of Canada, we don’t exist.”

Kakfwi is known for fighting against development of the proposed Mackenzie Valley Pipeline in the 1970s, his efforts to have Pope John Paul II visit the Northwest Territories in the 1980s, and establishing the Dene Cultural Institute, now known as the Yamozha Kue Society.

He received an Aboriginal Achievement Award for Public Service in 1997 and a Governor General’s Northern Medal in 2012.

Lawsuit

Kakfwi was named as a defendant in a lawsuit, alongside the Pierre Elliott Trudeau Foundation, last year, alleging that he sexually harassed his mentee in the scholarship program in 2018.

The suit alleges Kakfwi invited the woman to visit his home in Yellowknife and that he “grabbed her upper arm, close to her breast, and squeezed it” then proceeded to rub and massage it.

In a statement of defence, Kakfwi denied any contact that “could be construed as being sexual in nature.”

He claimed he invited the woman and another scholar to visit Yellowknife to “experience the richness of the northern Indigenous culture” and that he has previously hosted other scholars as travelling can be expensive.