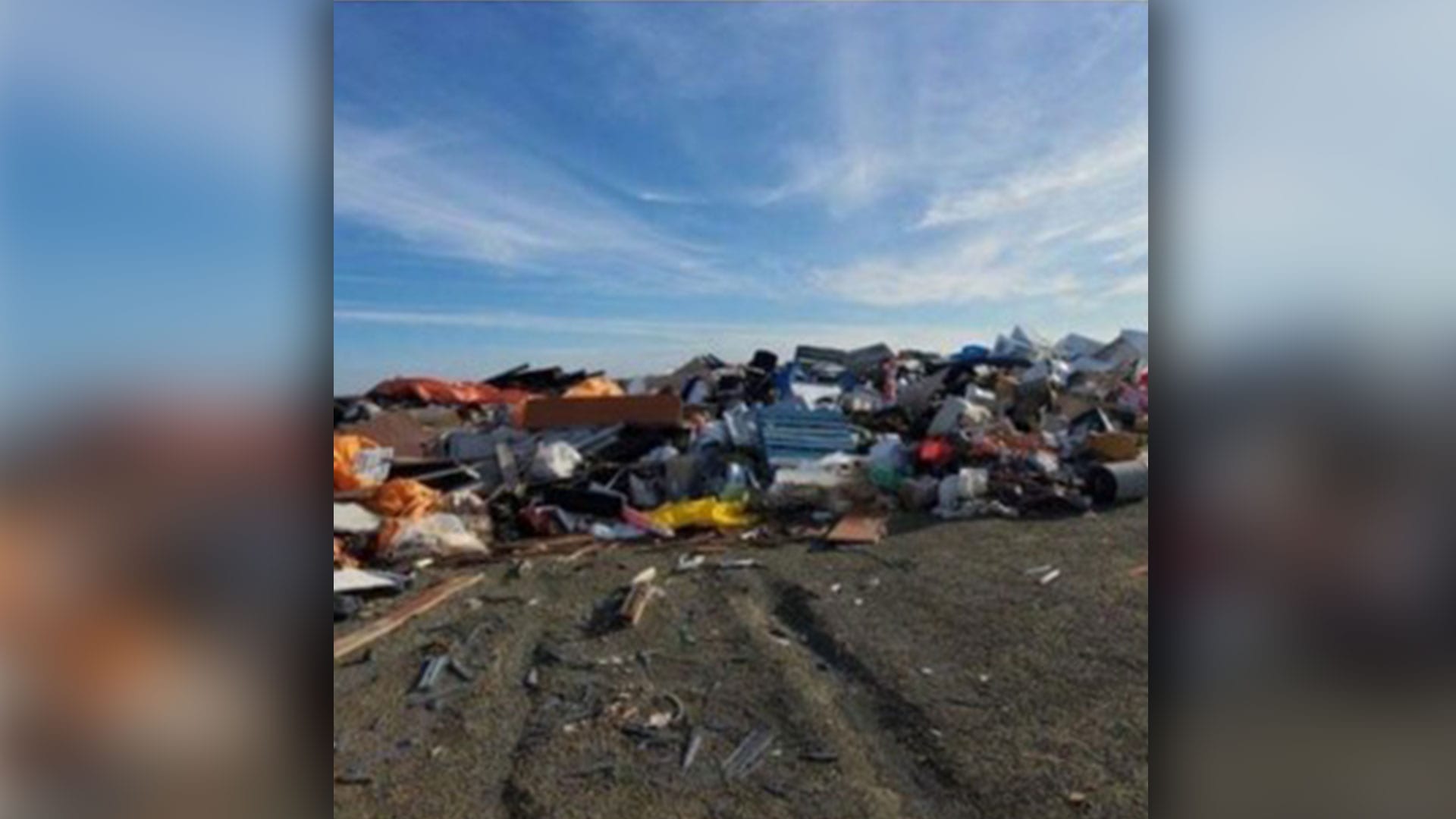

International diamond mining company De Beers wants to greatly expand landfill capacity to dispose of debris from the demolition of its northern Ontario mine. Photo: Attawapiskat First Nation

The Cree community of Attawapiskat wants the Ontario government to scrap a plan by mining giant De Beers to build another large landfill for non-hazardous waste at the site of its fly-in Victor diamond mine, which is located in the James Bay wetlands 90 km west of the coastal First Nation.

“The leadership said no,” explained Lands and Resources Director Charles Hookimaw. “The concern here is that there’s going to be more impacts to the precious environment that we have up there. We know all of that area is all just swamp and water, so we’re not going to support this and I think Ontario should say no.”

De Beers and Attawapiskat have had a rocky history when it comes to the mine, which began construction in 2006. The community ratified an impact benefit agreement with the company, but there’s also been past resistance in the form of protests and blockades.

Victor ceased operations last year and De Beers is now engaged in mine closure, demolition and remediation of the ecosystem. De Beers recently secured approval from Ontario to build a 97,000 cubic meter landfill in addition to a smaller one that already exists.

Attawapiskat and its consultants say the bid for a third site is an attempt to save money by burying waste that could be trucked out by winter road then shipped for recycling and reuse.

De Beers paid to maintain the winter road while the mine was operational, but no longer does.

“It’s like Ontario’s sleeping at the wheel here,” added Hookimaw. “They should be the ones policing the Victor mine, not Attawapiskat. That’s not our role. It’s Ontario that needs to protect our interest – that needs to protect the environment.”

Concerns over environmental assessment process

An environmental consultant working for Attawapiskat explains that closing a mine is typically a significant financial liability for a company because closing generates no revenue and companies have to be as cost efficient as they can.

“As closure moves forward, they have to meet regulatory standards. And they will be looking for ways to meet those standards at a low cost – which doesn’t always make the closure plan in the best interest of, say, a First Nation community that’s near a mine that may want to see a different set of standards,” Don Richardson told APTN News.

“They don’t want to pay for a winter road that would allow them to take all the materials from demolition and ship those south where they can be reused, recycled.”

Richardson, managing partner at an environmental consulting firm in Guelph Ont., says the way De Beers sought approval for the third garbage site should raise flags and would set “an unusual precedent” if approved.

He explained that 100,000 cubic meters is the threshold for a comprehensive environmental assessment for a landfill. At 97,500 cubic meters, the second landfill weighs in just under that. It had to go through a screening process, which it did in December 2018, but not a full comprehensive assessment.

“Put the two demolition landfills together with the very close timeline between finishing one and applying for another and you’ve got close to 200,000 cubic meters,” said Richardson. “If a municipality in southern Ontario was to try that I think they’d have a hard time convincing the local community that this was the right way to perform an environmental assessment.”

Ontario and De Beers respond

Ontario’s Ministry of the Environment says it’s aware that De Beers is considering a third landfill.

A spokesperson tells APTN that the ministry requested more information about the rationale for the third dump and has not yet determined what the environmental assessments would be for it.

“DeBeers has not submitted the requested information to the ministry,” said Gary Wheeler.

Wheeler says the ministry received a letter from Attawapiskat in July which raised community concerns over the landfill, which the government responded to in August.

“We responded to the Attawapiskat First Nation indicating that we had asked the company for additional information. We have offered to meet with Attawapiskat once we receive the information from the company.”

A spokesperson for De Beers was not available for an interview. But in a statement sent to APTN the company disputes the claim that they are prioritizing savings over environmental concerns.

“Placement of waste within the on-site landfill is a more environmentally friendly approach as compared to shipping the materials off to other landfills around the Province,” said communications officer Terry Kruger in an email.

“Responsible environmental management is our priority and we would not compromise that.”

De Beers is ready to sit down with Attawapiskat to discuss the community’s concerns, the statement said.

It stressed the company’s “strong track record” of protecting the environment, such as beginning mine reclamation in 2014 which resulted in remediation of 40 per cent of the site by the 2019 closure.

“Only 10-20 per cent of the material has potential to be recycled and would require approximately 1,200 truck loads to remove from site should markets for this material be available, which would create its own environmental impact,” wrote Kruger.

“We have not ruled out the option of shipping some items off site for recycling should it prove to be a more responsible approach.”

Concerns over plan to scale back water monitoring

None of this sits well with Hookimaw, who accuses Ontario of letting De Beers “do whatever it wants to do” without adequate oversight in the pristine peatlands of the Attawapiskat River watershed.

“It’s out of mind, out of sight,” said Hookimaw, “and Ontario is turning a blind eye here and nobody says anything.”

He says Attawapiskat is worried about the mine’s plan to scale back its water-monitoring wells that allow frequent testing for contaminants in the water system.

“We asked Ontario not to support it,” said Hookimaw. “We said it’s too soon. We need to understand what the impact is going to be and how it’s going to affect the environment and the people of Attawapiskat.”

As a mine digs deeper, groundwater can accumulate in the pit, which necessitates an extensive system to pump water out to keep everything dry. This process is called dewatering.

The wet ecosystem of the James Bay Lowlands made dewatering a constant concern throughout the mine’s lifespan.

Richardson explained that once water monitoring wells are shuttered, they’re basically shuttered for good.

“For Attawapiskat First Nation trying to understand the long-term impacts of the mine, once those monitoring wells are closed, it’s very expensive to bring them back as effective monitoring wells because you’d have to re-drill them,” he said.

“It’s good practice if you’re going to close a mine to ensure that there’s long-term water monitoring, that’s a basic principle.”

In a news release, Chief David Nakogee accused De Beers of “turning our lands into their garbage dump instead of building a winter road.”

The company took the criticism in stride.

“We share Attawapiskat’s desire to complete the closure and rehabilitation process in the most responsible manner and this is the focus of our planning,” Kruger replied.

De Beers says it expects to complete reclamation by 2024. When operations stopped last year, the company said it had extracted 8.1 million carats of diamonds, spent $2.6 billion on construction and operation – of which $820 million went to First Nations and local businesses – between 2008 and 2019.

Hookimaw says the community is considering options depending on what happens with the landfill.

“It’s up to the leaders up in the community how they want to direct my office what the next steps are going to be,” he said.

“Our legal team and our technical consulting group will go back to the drawing board how we’re going to move forward.”