The first time Gordon Bluesky was going to meet his birth mother and extended family, it was supposed to be with his two sisters.

When the sisters missed their flight, Bluesky made the trip on his own.

Bluesky and his sisters were apprehended from their family in Brokenhead Ojibway Nation, north of Winnipeg, when he was around two years old. He spent the next few years in foster care, sometimes with his sisters, sometimes without.

All three would end up being adopted together as part of what is called the ‘60s Scoop by a family living in a little town outside of Pittsburgh, Penn.

During that initial visit in Brokenhead, Bluesky admits he was really nervous and spent a lot of time in the bathroom in the basement, hiding from the people waiting to meet him.

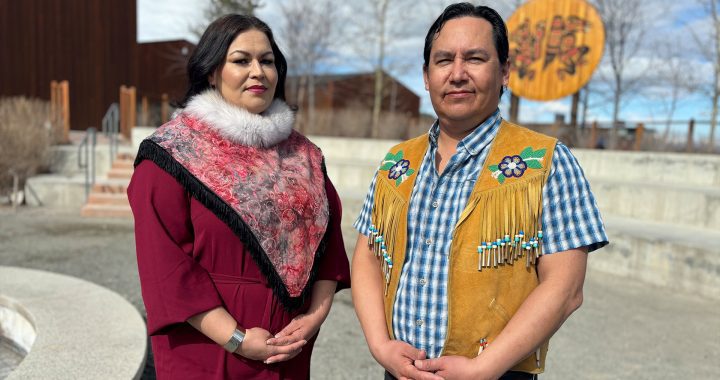

“This moment was meant to be with my sisters, but I ended up going upstairs on my own,” says Bluesky, who is now chief of Brokenhead Ojibway Nation. “But it was the most amazing moment, as well, because I walked into a room full of people that looked like me, that were my relatives, that were my blood, and I’d never experienced that in my life – other than with my sisters. I’ll always remember that moment for the rest of my life.”

“I also found out in that moment that I had two younger sisters and at that time they were only 2- and 4-years-old – and that was amazing. I pretty much started crying at that point because I had no clue they even existed.”

Soon after, Bluesky would move back to Canada.

One of the first things he remembers thinking upon his return is that he wanted to be chief one day.

Twenty-seven years later, he is a little more than a year into his first term.

He tells Face to Face host Dennis Ward it’s been a challenge to be chief for a nation where members are dealing with a lot of trauma from the historical legacies that have carried over from the residential school system and the ‘60s Scoop.

Bluesky had his own trauma to deal with.

“I was taken from my community and I don’t remember. I have a faint memory of my grandmother. Ultimately, when I started to remember things, it was trauma, it was scared, it was sadness,” he says. “It was dark things that I don’t even want to talk about but it was things that I remember and those were my earliest childhood memories and I know a lot of our people share the same experiences that I have and so we have to work our way through that.”

Bluesky says it has taken a lot for him to get to a place where he doesn’t allow trauma to dictate what he does in his life.

He is also a Stage 4 cancer survivor.

Bluesky is of the belief that trauma, if it is not released, can manifest itself into sickness or disease.

Six months before his cancer diagnosis, he drank alcohol and took drugs for the last time.

He asked for help and entered a treatment centre and is now seven years sober.

Bluesky says once he kicked his dependency on drugs and alcohol, he could begin to work on himself and the trauma that he was ignoring and masking with his addictions.

He feels fortunate to live in a time when Indigenous peoples can practice ceremony openly and says he has strong healers that he works with.

Bluesky is also chairperson of Treaty One Nations Inc., which is comprised of seven Treaty One First Nations and responsible for developing the largest urban reserve in Canada.

Naawi-Oodena is a 109-acre piece of property in the city’s south side, and provides what is believed to be a once in a lifetime opportunity.

“It’s going to be a kickstart to our economic engines and really get our communities, not only working, generating much needed revenue but also just pride,” says Bluesky.

“I’ve been explaining this to the City of Winnipeg and other groups, saying that we want to see relationships start to build here, we want to see internships with different companies, we want to see internships for policing of this property and other things. I’ve got family members who work at the City of Winnipeg, that now can work at Naawi-Oodena; it’s an amazing opportunity, I can’t wait to see it,” he says.

“They figure about a 15- to 20-year build out and I’m hoping to see it all the way through that but its something that I think we can all be proud of as Manitobans, Winnipeggers, Canadians,” says Bluesky, who noted that an announcement is expected in the coming weeks on construction.