Like many Indigenous siblings separated by adoptions, half-sisters Raelene Recksiedler and Helene Rosenzweig-Schmidt always felt like something was missing.

They met for the first time in Winnipeg on June 29, 2022. They are just 44 days apart in age and didn’t know each other despite sharing the same father.

Recksiedler, a Red River Métis woman who has lived in Winnipeg all her life, recalled how she would beg Santa for a sister.

“I remember asking Santa for a sister,” she said, “Every Christmas when I would sit on his knee ‘I want a sister for Christmas! I want a sister for Christmas!’ But you know, she never came.”

Rosenzweig-Schmidt was adopted by a Jewish family in Upland, California at five months old. Her Cree mother gave birth to her in The Pas in northern Manitoba before the adoption.

They uploaded their DNA to the online website 23andMe, a DNA testing service that identifies a client’s genes, ancestral make-up, and any family members also in the website’s system.

The sisters were notified that there was a match.

It was in December 2021, just a week before Christmas that Santa finally delivered on her request – just five decades late.

The sisters connected online and Recksiedler said they were both overjoyed.

“I think we talked that first night for like two or three hours,” she said, “We just shared pictures and we talked about absolutely everything. In that two hours, it was like we knew each other for fifty-two years.”

“It was a lifetime wrapped up in a two-hour conversation,” Rosenzweig-Schmidt added.

The Missing Link

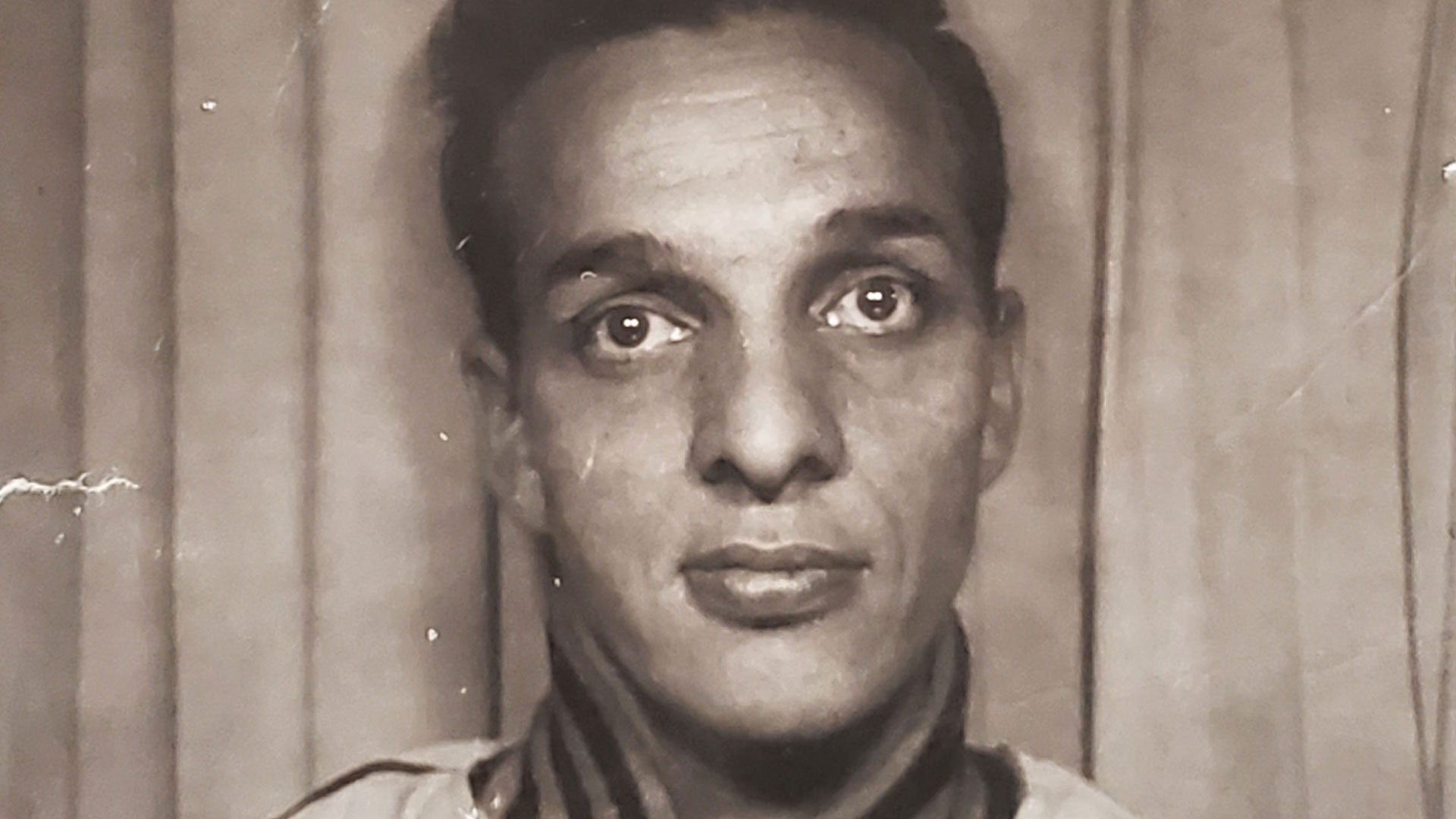

The sisters soon found out that they shared the same father, Raymond Kobold.

Recksiedler knew him as dad for the first 17 years of her life until his death in 1987 at the age of 48.

While the sisters aren’t positive about what happened, they theorized that Kobold must have had an affair while up north for work. That affair with a northern Manitoban woman resulted in Rosenzweig-Schmidt’s birth.

To complicate matters, Recksiedler was conceived just weeks after and so both girls were born in the same year. She says that she didn’t know much about her dad’s background.

“Fifty per cent of me was missing,” she said, “I didn’t know who my paternal side [was] because my birth father never spoke of his family. He never spoke about anything.”

What she did know about his life was typical of many Indigenous kids of the ‘50s and ‘60s.

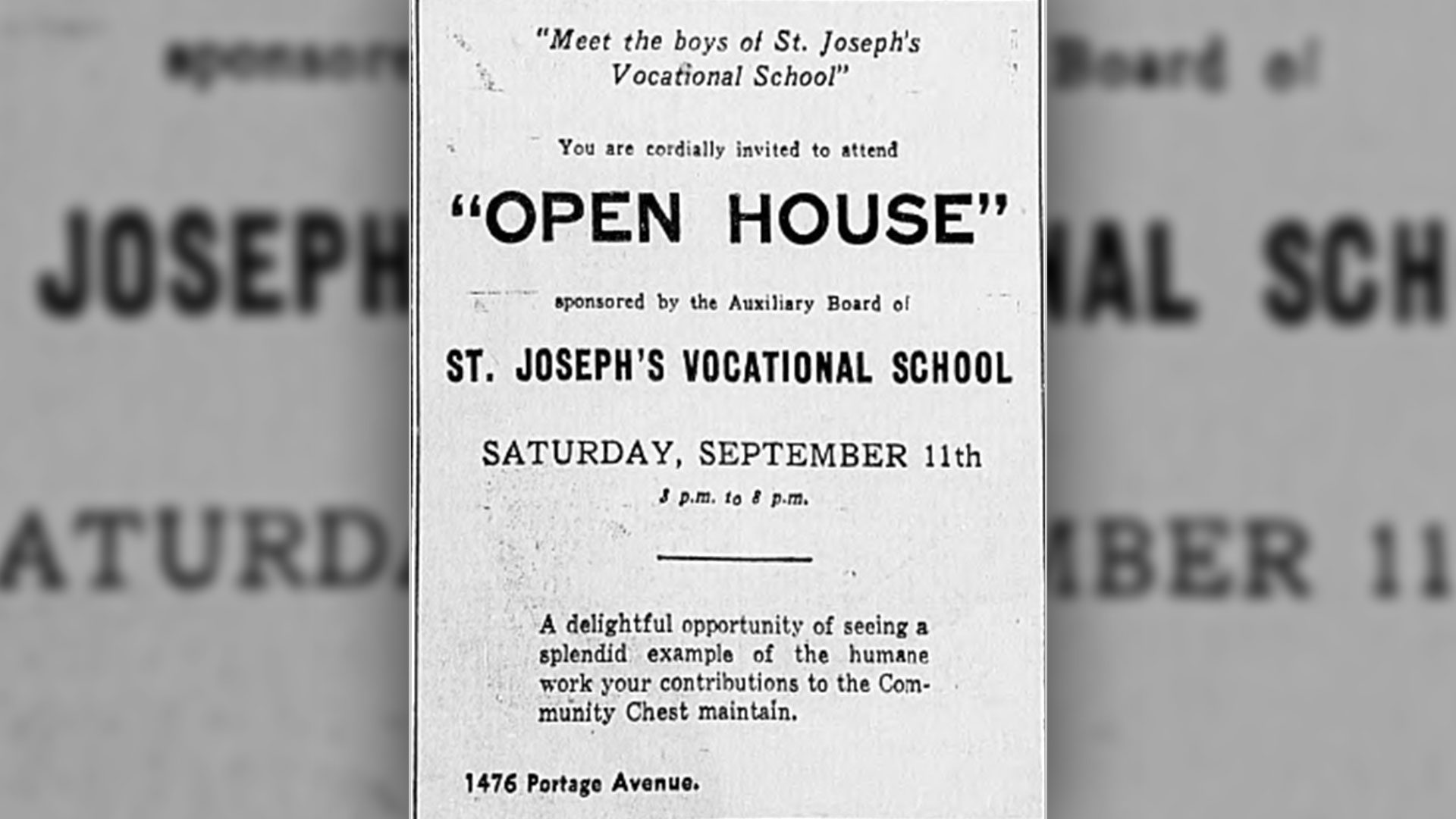

He was apprehended from his parents as a toddler along with his two brothers and placed into care by the Children’s Aid Society. He was then turned over to the sisters at St. Joseph’s Vocational School for Boys in Winnipeg.

St. Joseph’s was a catholic-run orphanage that turned into a boarding and trade school partially funded by both the provincial government and the city.

Tragically, the Sisters of Providence did not deliver on their duty to nurture Kobold, and instead, he was subjected to abuse.

“He was not a kind man, he lived by the belt. In his life, it was hit and if you cried you got hit even harder. So, you had to learn how to not cry if you were hurt.

“I never really learned how not to cry. I was a very soft person, and I felt things,” Recksiedler remembered with tears in her eyes.

Her childhood was marked by loneliness and secrecy.

“I remember my mom telling me that she would always go looking for me and she’d always find me asleep in my closet in my bedroom,” she said, “I’d always have my toys with me because I would be afraid. I’d be alone in my closet playing by myself.”

She said having a sister may have made all the difference.

“I think I would have had an ally,” adding that at least they could have hidden together.

Growing Up Apart

Helene Rosenzweig-Schmidt’s adoptive family had a different type of influence on her upbringing, one which was unaffected by Kobold’s trauma.

“I thought maybe he was like a movie star, I didn’t really know what kind of man he was. I always wondered,” said Rosenzweig-Schmidt.

She said though she was curious about her birth father, it wasn’t something she dwelled on because she had a happy childhood and loving parents.

“It’s a very positive family. I was very lucky God placed me in a wonderful family,” she stated, “I had a dad who was there when I scrapped my knee and when I took my first step. I have recordings of him doing the alphabet with me. It’s just… that’s my dad. That’s my dad.”

She proudly told the story of when her adoptive parents received news that she’d be joining their family.

“They actually received the call that [I] was available on the day they were coming home from the cemetery from burying my grandmother,” she said.

“For my family, of course, they’re mourning but yet here comes this positivity. I was meant to be for them. It means a lot to me that I was a gift for them.”

Rosenzweig-Schmidt remembers family road trips, Sunday school, stable parents, and the innocence of not knowing anything different.

However, learning about the plights of her sister and birth father was eye-opening.

“That was a lot for me to understand about the kind of man that he was. I’m thinking ‘If I was with him, would that have happened to me?’”

Though there were stark differences in their childhoods, the young girls also shared unique similarities.

Both were born with a genetic disorder called neurofibromatosis 1 (NF1), passed down to them through Kobold.

With NF1, a person develops tumors on the nerve endings throughout their body, sometimes growing large enough to impair mobility and require surgery. Though more often benign, the tumors can be cancerous and are nonetheless visually apparent.

While Recksiedler grew up with a father and brother with the same condition, Rosenzweig-Schmidt was alone. Having no family history to go off, the doctors concluded it was a spontaneous mutation.

Through this shared disorder, they found further understanding of themselves and strength in each other.

Reconnecting

Loss of culture is another area where they can relate. Recksiedler and Rosenzweig-Schmidt both grew up without knowledge of their Indigenous cultures and identities.

For Recksiedler, this is attributed to the cultural loss her father experienced due to his apprehension and schooling.

But for Rosenzweig-Schmidt, across the border and adopted into a non-Indigenous household, it was a different story.

“I was just taught that I was Cree Indian and that was all that was ever said. I was never brought up learning anything about my heritage. The only heritage that I learned was that I was Jewish, that I was adopted into a Jewish family,” said Rosenzweig-Schmidt, “I was never taught my heritage at all from my family because they had no knowledge so what can they teach me if they don’t know anything?

“I didn’t actually feel like I belonged to anything without knowing anything about my own heritage outside of my adoption.”

When the topic of reconnecting came up, the differences arose once again.

Recksiedler has spent the past few years actively reconnecting and learning more about her family and the history of the Métis nation. She finally became a citizen of the Manitoba Métis Federation, also known as the MMF, in 2021 -something she said she’s proud of.

“I think it is really an amazing thing to know that my ancestors founded the land and worked this land,” said Recksiedler, “That I am able to be here and be able to carry on that same heritage that they fought for.”

The process is more difficult for Rosenzweig-Schmidt, who lives in Colorado and without much immediate connection to her Indigeneity.

“In some ways, I want to know more about it but I don’t know if I really want to, if I’m ready yet for that,” said Rosenzweig-Schmidt.

“It’s a big, huge step for me to take. It’s all new to me and it’s a lot of information that I have to process. And it’s emotional.”

The Road Ahead

After having finally met in person, the sisters are becoming an unstoppable force to be reckoned with.

They have already begun to share parts of their story with a new television show debuting next year and they are vacationed in California this past summer so that Recksiedler can meet Rosenzweig-Schmidt’s adoptive family.

“We don’t know what tomorrow holds so we’re just going to hold on to what we have today,” said Rosenzweig-Schmidt, “We just cherish the memories that we make.”

And that feeling is mutual.

“I just wanted to know your smell and to feel your touch and to be able to remember that. You’re absorbed into my senses now and into my memory,” Recksiedler expressed gratefully.

Rosenzweig-Schmidt said that as an adoptee there is a great level of difficulty when entering someone’s life as a stranger and hoping for their acceptance.

It was, luckily, the exact opposite when she saw her long, lost sister for the first time.

“I knew she was going to be accepting. It wasn’t going to be her not wanting to hug me or embrace me. It was there, and it was true and it wasn’t fake,” said Rosenzweig-Schmidt.

“We weren’t putting on an act, it was genuinely what it was supposed to be.”

The same can be said for Recksiedler who said that, next to her kids, Helene is one of the greatest gifts she’s ever had in her life.

“Having a blood-related sister means more to me than anything,” she concluded, “I can honestly say the one thing Ray has done right is made me a sister.”