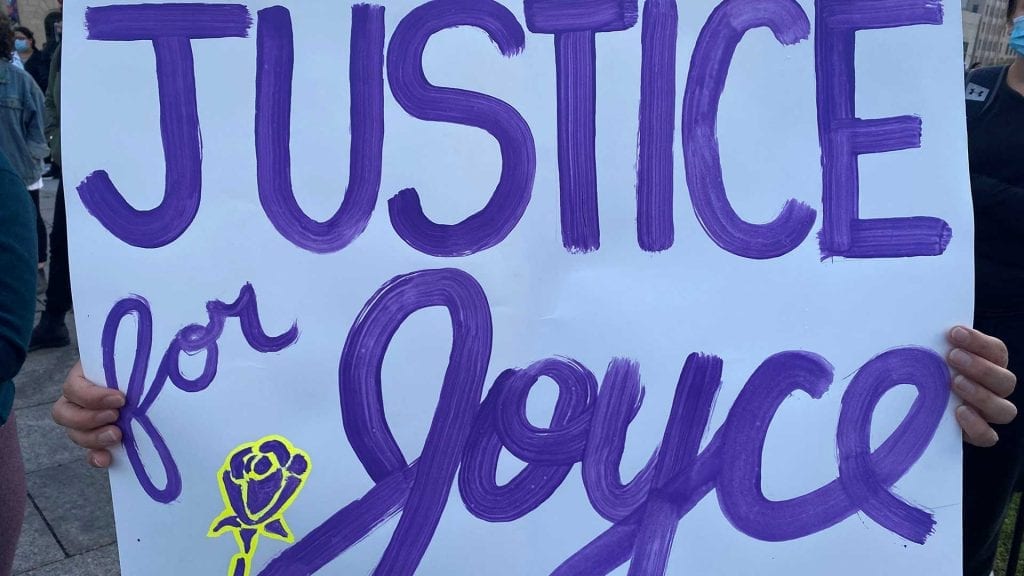

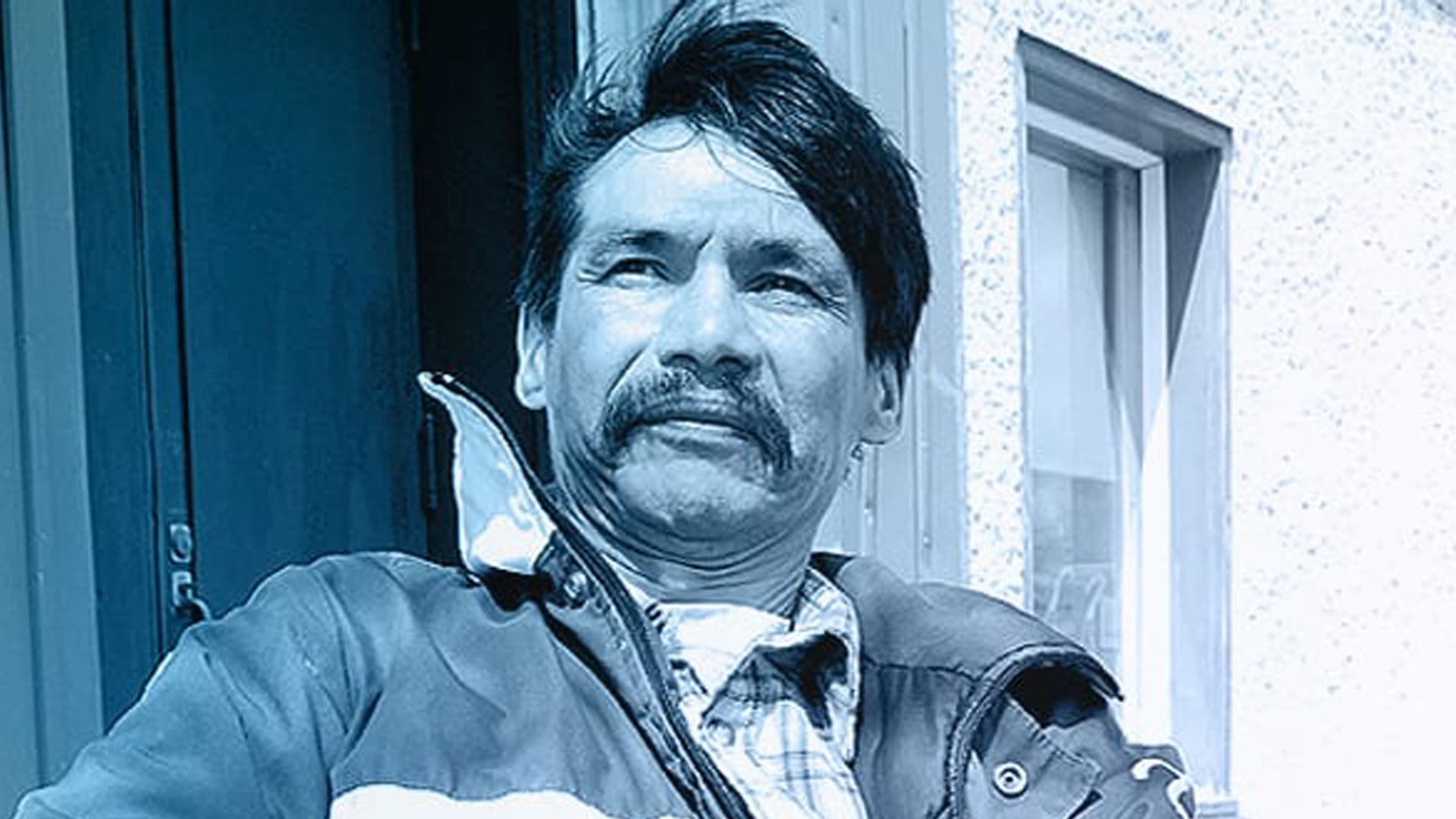

The racism Joyce Echaquan experienced prior to her death in a Quebec hospital has sparked outrage and a "justice for Joyce" movement. Photo: Jamie Pashagumskum/APTN

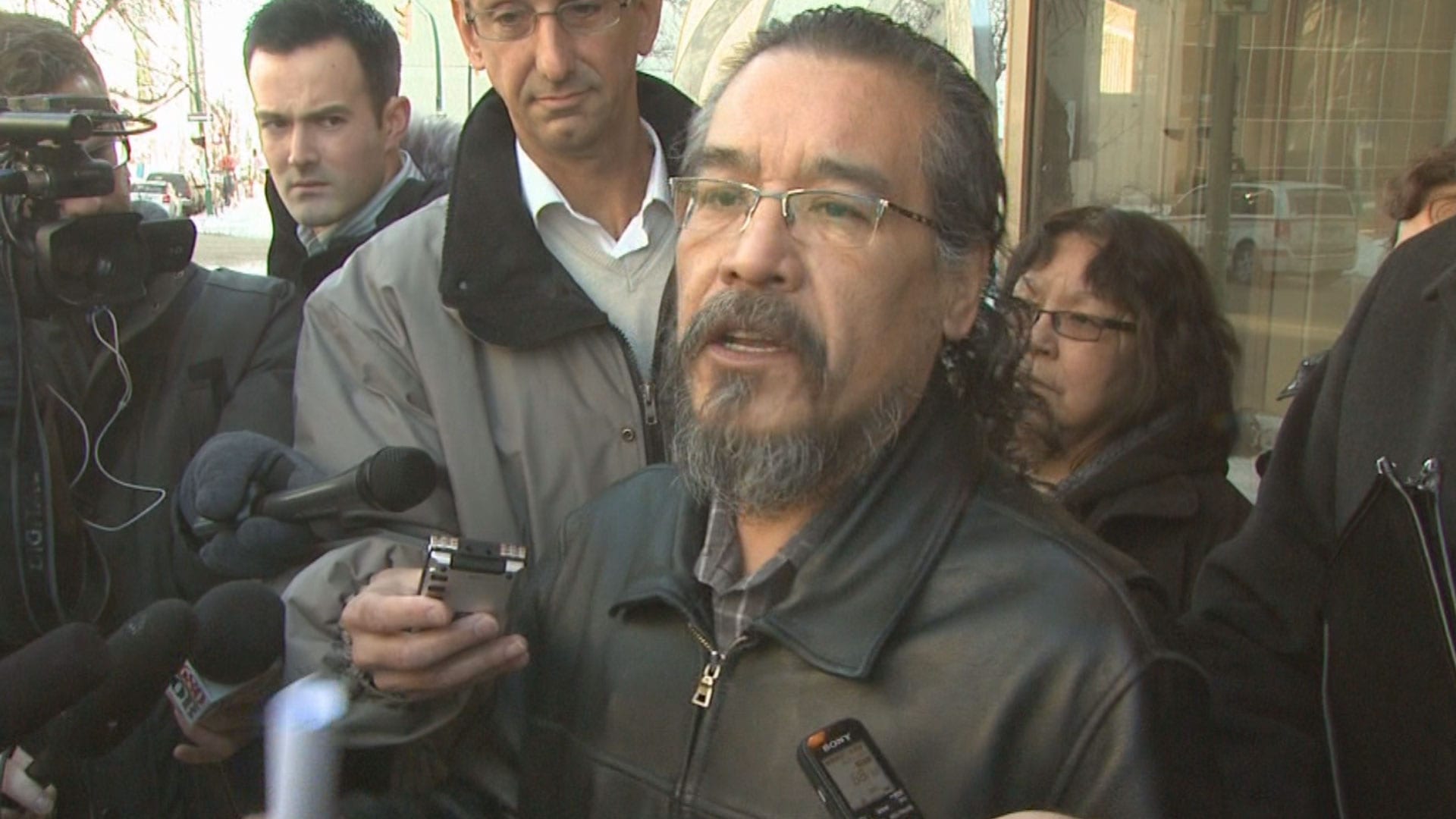

Robert Sinclair has a short but strong message for the family of Joyce Echaquan.

“Never give up,” he urged, still seeking answers 12 years after his cousin Brian Sinclair died from sepsis in a Winnipeg hospital after waiting 34 hours to receive care that never came.

“It’s worth all the time that you could spend on this to make changes, even if they’re little changes.”

Echaquan, an Atikamekw Nation mother of seven, live-streamed the vitriolic, denigrating racist insults that health-care workers hurled at her before she died in a Joliette, Que. hospital earlier this week.

Her family are now in the same place Robert Sinclair was over a decade ago – thrust before the media’s bright lights, searching for answers, calling for justice and all the while mourning the sad loss of a loved one.

“I would advise them to keep it alive. Keep it going. Don’t let other people end up like this, to be mistreated and to die,” Sinclair said in an interview with APTN News.

“But to stay strong as well. We know that this happens. As an Aboriginal person, I know it happens because I’ve felt it. It’s an odd kind of feeling to feel that racism.”

The country is reacting with consternation, sadness and outrage over the mistreatment of the 37-year-old from Manawan, about three hours north of Joliette, which is itself an hour from Montreal.

Two health-care workers have been fired. Officials have called for an inquest and local coroner André Cantin has already begun an investigation.

Though Echaquan’s mistreatment has drawn comparison to Brian Sinclair’s, there are other documented high-profile cases of medical mistreatment.

Raymond Silverfox died from acute pneumonia in a Yukon RCMP jail cell after officers mocked and taunted the dying man, assuming he was drunk, in 2008.

Joyce Tapaquon believed racism contributed to her terminally-ill daughter Juliette Tapaquon’s mistreatment after she was kicked out of palliative care in Saskatchewan.

Other sources tell APTN that this experience isn’t unique to one family or one part of the country.

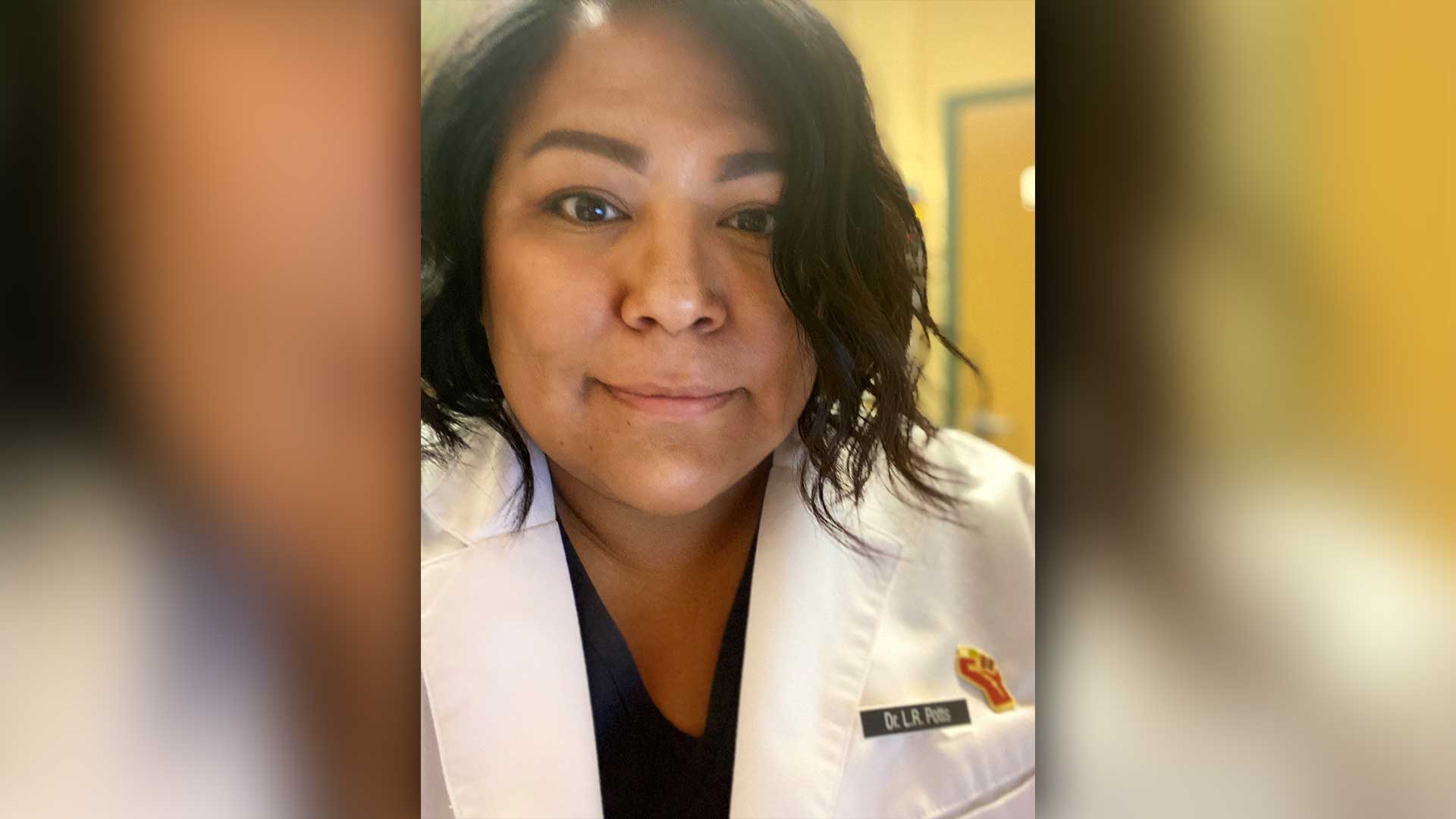

Prominent Blackfoot doctor experiences racism “100 per cent of the time”

Racism is a regular occurrence for Dr. Lana Potts, a member of the Blackfoot Piikani Nation.

She’s one of only a handful of First Nations physicians who’ve been meeting regularly with Crown-Indigenous Relations Minister Carolyn Bennett, pushing for change at the highest level since COVID-19 gripped the country.

Potts is brutally honest about her experience with racism in health care. As a nurse and even as a doctor in her own workplace, discrimination is a daily fixture in her life as a dark-skinned, proud Blackfoot woman.

“I’ve worked across the country, I’ve trained in Thunder Bay, I’ve trained in Victoria, I’ve trained in Edmonton and in Calgary, and some of the most racist environments I’ve worked in have been health care,” she told APTN.

“One-hundred per cent of the time, as a physician who’s accessed health care, I’ve experienced racism. I’ve started wearing a white coat to work. I don’t normally wear a white coat and I did for COVID reasons.

“And all of a sudden the racism has decreased. I stopped getting followed by security. I stopped being told I was high on pills and needed to leave my own office building. So, if I’m encountering it and I work there – with a badge with my name on it and people see me on a regular basis – I could not imagine what people are encountering.”

It’s a sentiment Sinclair echoes.

“We’ve been telling the problems with the health-care centre for years now. Then this happens. There’s other cases as well, I imagine, across Canada,” he said. “This one sticks out because she actually taped it and showed the racism, the live racism.”

Shortcomings of coroner’s inquests

When asked what the Echaquan family could expect from a coroner’s inquest, Sinclair is blunt.

“That same bullshit that they gave us at the inquest,” he replied. “It wouldn’t even touch on any of those subjects: stereotyping, racism, assumption making. That’s why we boycotted the whole inquest at some point.”

The family eventually pulled out as the inquest proceeded. They felt the coroner narrowed the scope too much. They wanted a full provincial public inquiry.

It never happened.

Twelve years later, they remain engaged in litigation against the Winnipeg Regional Health Authority, feeling like justice was never served.

“Right from the beginning I asked for the truth. They won’t even touch on the truth, the real reason why he died. They wrote it off as bad assumption making – it was clearly racism at its finest happening there at that time,” he said.

Drew Lafond, president of the Indigenous Bar Association and member of Muskeg Lake Cree Nation, points out that coroner’s inquests can have shortcomings in situations like this.

“Indigenous peoples have very little or any faith in the coroner’s inquest processes. One of the key reasons is because the investigatory tools that are available to the coroner in that case are very limited,” he said.

“It’s not as though they’re conducting a criminal investigation with binding consequences. No charges will be laid as a result of the coroner’s inquest. The coroner doesn’t have the discretion to lay charges, so there are very little repercussions rising from a coroner’s inquest.”

They can also offer a list of recommendations to prevent similar deaths in the future, but this is discretionary under Quebec’s Coroners Act.

Lafond has personal experience with this process and those shortfalls.

A coroner’s investigation into his aunt’s death produced “very little, if any, facts or any findings to give the family any comfort,” he said.

“Once you do go through one of these processes, you really do realize how limited that they are, how the justice system is not as invested in these processes as they would be for a criminal investigation say if this were a homicide or deemed to be a homicide.”

Possible criminal investigation?

Some are calling for criminal charges to be laid in Echaquan’s death. Lafond says a criminal investigation is a possibility.

“I think the facts in this case certainly lend themselves to a criminal investigation, because there’s a large question about whether her death could have been prevented,” he said.

Like the Sinclair family, Echaquan’s family can pursue legal action against the hospital, which they are expected to do.

“If the care that any patient receives was somehow negligent, and if their death or some injury results from the negligent treatment, then they have the right to bring a civil claim,” said a co-counsel for the Sinclair family, Vilko Zbogar.

“Beyond an inquest, that’s really one of the ways that you can hold the system accountable. It’s a process in which the family has some control over what issues come forward.”

The coroner’s investigation is proceeding confidentially. Aside from the evident racism in the video, any allegations of criminal negligence remain untested.

Zbogar also says coroner’s inquests have shortcomings, in particular when people feel change is required at structural levels.

“Even if they find some serious problems and make some important, meaningful recommendations – they’re only recommendations. They’re only on paper, and it really takes some courage and political will to actually take those recommendations off the paper and give them life.”

Lafond agrees the process of investigation and inquest can be “frustrating” for Indigenous people who want action and change immediately.

“Why I say it’s frustrating is because there was already a public inquiry commission on relations between Indigenous peoples and certain public services in Quebec titled Listening, Reconciliation and Progress, and that final report was released just last year.”

This inquiry is commonly called the Viens Commission. It was headed by Justice Jacques Viens and represented for Quebec the sort of full judicial inquiry into institutional discrimination that the Sinclair family sought but never had in Manitoba.

“They’ve been trying to sweep it under the rug for years by not allowing an inquiry which would broaden the issue,” said Sinclair. “I don’t believe that these are isolated incidents because it continues to happen even 12 years later.”

Lafond points to nearly two dozen reports dealing with similar issues and offering actionable recommendations.

“We have 21 reports over the last 30 years that have spoken directly to that matter and systemic instances of racism which lead to outright violence and discrimination against Indigenous peoples.”

While health-care policy is under provincial jurisdiction, Potts notes that Ottawa has a responsibility toward Indigenous people along with the ability to act.

“Enough is enough,” she said. “We need to start to move forward. We can’t just continue to say, ‘We acknowledge it. It’s there. We’re going to have an inquiry.’ We actually need to have action and legislation to be able to make people accountable.”

“If we don’t start to really look at the factors that are affecting people’s lives and their outcomes, we really need to ask ourselves what type of future are we providing for our children? We need to start to talk about racism, we need to start to really say those words.”

For Sinclair, the struggle continues.

“Hopefully I live long enough to see some real transparency in that system. Make people accountable for the shit that they do there,” he said.

“I don’t know all the answers, but hopefully we will get the right answer one day – and the right answer is the truth.”