Little has changed for Indigenous peoples in prison over the past decade, says the Office of the Correctional Investigator of Canada (OCI).

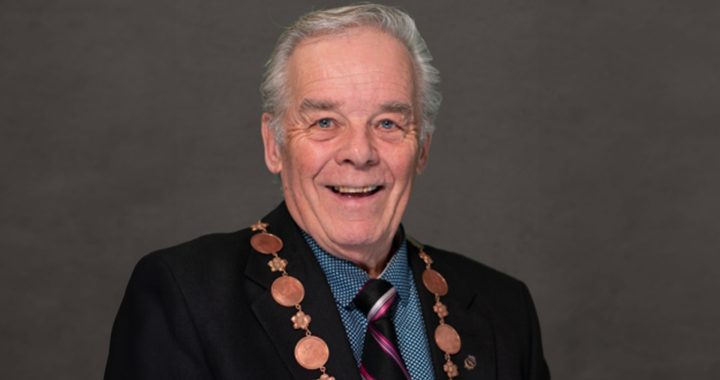

Ivan Zinger says they continue to be caught in “the proverbial revolving door” of the justice system without being able to get out.

“It appears that, at the highest levels, CSC [Correctional Service of Canada] does not seem to accept that it has any role or influence on reversing the perpetual crisis of Indigenous overrepresentation in Canadian jails and prisons,” Zinger says of his 2022 annual report.

“A corporate culture and a prison system that are resistant to change can only serve to keep Indigenous Peoples marginalized, criminalized and over-incarcerated.”

The report shows 32 per cent of the prison population is made up of Indigenous peoples.

A number that Zinger says continues to grow despite his regular, critical analysis of corrections, which is responsible for federal prisons in Canada.

“We found, again, terrible outcomes… these include, for example, being over-represented in use of force, over-represented in maximum security institutions, over-represented in structured intervention units, which is the former administrative segregation regime,” Zinger told reporters in Ottawa.

“They are more likely to also be labelled as gang members, they’re more likely to self (injure), they’re more likely to attempt suicide. They’re also over-represented in the last fiscal year, in terms of suicide, by the six individuals that committed suicide last year were Indigenous.

“They also serve a far greater proportion of their sentences compared to non-Indigenous people.”

APTN News was the only media present at the news conference in Ottawa.

Zinger first sounded the alarm about the looming crisis involving Indigenous Peoples in Canada’s penitentiaries in 2012 through a report called Spirit Matters: Aboriginal People and the Corrections and Conditional Release Act.

That report outlined the need to decrease the number of Indigenous offenders in prison and offer more programs to help them reintegrate back into society.

It recommended CSC concentrate on several key areas including expanding healing lodge programs, increasing early releases, appointing a deputy commissioner of Indigenous corrections, improving custodial and community-based programs, and increasing the number of Indigenous employees within corrections.

Fast forward to 2022 and Zinger says the CSC has done little to move on decades of recommendations.

Indigenous women in prison by the numbers

In December 2021, Zinger announced a dire milestone: Indigenous women, who comprise less than five per cent of the population in Canada, represent 50 per cent of the women locked up behind bars across the country.

“Surpassing the 50 per cent threshold suggests that current efforts to reverse the Indigenization of Canada’s correctional population are not having the desired effect and that much bolder and swifter reforms are required,” he said at the time.

Despite repeated calls for reform, Zinger says the situation is not getting better – or it seems – even slowing.

Neither are the outcomes for Indigenous women who, for instance, make up 65 per cent of the inmates who are classified as maximum security offenders, according to Zinger’s latest report.

Additional statistics show that 20 of the 29 Indigenous women classified as maximum security were born after 1990, “reflecting a younger population,” he said.

Even programs aimed at helping women in prison seem to exclude Indigenous women.

Since 2002, 183 mothers have applied to participate in the Mother-Child program to “foster positive relationships…and to provide a supportive environment that promotes stability and continuity for the mother-child relationship.”

But CSC says only 53 (or 29 per cent of) First Nation or Métis mothers have been accepted to participate. No Inuit women have applied to take part.

The low rate of participation, Zinger says, can be attributed to the program’s criteria set by the CSC.

“The high rates of Indigenous women with a maximum-security classification make them ineligible for participation,” he explains. “In addition to the exclusionary criteria, the required involvement of child welfare agencies may serve to discourage Indigenous women from applying to participate altogether, given the uniquely painful history and continued involvement of child welfare agencies in the dissolution of Indigenous families, particularly through the Sixties Scoop and placement of Indigenous children in the foster care system.

“In keeping with the calls-to-action of recent parliamentary reports, government commissions and national inquiries, and given the issues as noted by this Office and the Library of Parliament, the (CSC) must make more intentional efforts to keep Indigenous mothers connected with their children.”

Bureaucratic delay and inertia

None of this information should come as a surprise to Public Safety Minister Marco Mendicino who is responsible for corrections or its commissioner Anne Kelly.

Decades of reports have been written by several federal agencies, parliamentary committees, non-governmental organizations and national inquiries outlining the deficiencies in Canada’s prison system and how it treats Indigenous people.

In fact, Zinger’s report is the third of its kind in 2022 alone.

A report released Oct. 26 by a committee struck by Public Safety Canada (PSC) and led by former correctional investigator Howard Sapers, said Indigenous Peoples make up a disproportionate number of inmates serving time in what are now called a structured intervention unit, or SIU.

The SIU replaced segregation or solitary confinement units after several court cases deemed them inhumane because prisoners were isolated, at times, for days and even weeks.

Saper says in his new report that Indigenous inmates make up 48.9 per cent of the people in the new prison SIU system.

“Simply put, the impact of SIUs is not even across groups of people in Canada and is unequally experienced among penitentiary groups. Indigenous Peoples are clearly over-represented in the SIUs,” he wrote.

Auditor General Karen Hogan issued a scathing report of the correctional system in April stating that the problems highlighted over decades are being ignored by CSC.

Hogan’s audit found CSC “failed to identify and eliminate systemic barriers that persistently disadvantage certain groups of offenders.”

For instance, audits of CSC from 2015, 2016 and 2017, “found barriers to the timely preparation for release for the majority of offenders in custody.”

In particular, Hogan found that “more Indigenous offenders were placed at maximum-security institutions on admission than non‑Indigenous offenders, and that they did not have timely access to correctional programs, including those specially designed to meet their needs.”

According to Hogan, Indigenous Peoples face “disparities” the moment they arrive at the institution and the process for assigning a security classification (maximum, medium, minimum) called a Custody Rating Scale (CRS), resulted in a “disproportionately high numbers of Indigenous and Black offenders being placed in maximum-security institutions” on admission at nearly twice the average rate of other offenders.

The CRS has been highlighted in four different federal studies since 2001 – each one of them calling for a review or overhaul of how corrections determines an inmate’s threat to themselves or others.

Are statutory release prisoners prepared for the outside world?

Hogan’s audit also outlined the problem with prisoners being assessed as a higher security threat meaning they’re less likely to be paroled early in their sentence – and more likely to be freed on statutory release after serving two-thirds of their time.

According to Hogan, when prisoners are released before the end of their sentence, they get assistance to support their “successful reintegration into the community.” But she found fewer services and controls are in place for prisoners who are freed under statutory release.

“More Indigenous offenders remained in custody until their statutory release and were released directly into the community from higher levels of security. As a result, Indigenous offenders had disadvantaged access to a gradual and structured return to the community under parole supervision before the end of their sentences.”

Reviews taking place

According to responses from CSC and Mendicino’s office, reviews are taking place to “address systemic racism and the overrepresentation of Black and racialized Canadians and Indigenous Peoples in the justice system.”

“This will build on the many important steps we’ve already taken to address the overrepresentation of Black and Indigenous (particularly) women offenders,” Mendicino said in a release, “including introducing Bill C-5 to address harmful mandatory minimum sentences, developing an Indigenous-informed security classification process, creating the new position of Deputy Commissioner for Indigenous Corrections (a previous OCI recommendation) and implementing CSC’s Anti-Racism Framework and Actions.”

“To date, we have implemented over 90% of the commitments we put forward in our responses to the OCI’s recommendations in the last 10 years,” Anne Kelly said in a statement.

“I recognize there is always more work to do and remain committed to ongoing and continuous progress to implement our commitments, including the new actions put forward in response to today’s report.”

When asked about CSC’s assertion it implemented 90 per cent of the recommendations from his reports, Zinger disagreed and said he continued to be disappointed with the Crown corporation.

“…Progress has been far too slow and in some cases non-existent,” he said. “As detailed in my annual report, there has been very little progress, in particular with respect to the creation of new healing lodge spaces, Indigenous representation, and cultural competence among CSC staff.

“On a positive note, I would like to acknowledge that CSC has noted my call to redistribute a significant portion of resources to Indigenous communities – I certainly hope this translates into action.”

Creating the deputy commissioner of Indigenous corrections was, as it has been a dozen times before, one of Zinger’s recommendations.

According to a CSC, “we have launched an open and transparent process to hire a Deputy Commissioner for Indigenous Corrections,” the CSC said in a statement to APTN. “We are now accepting applications.

“This new position will support relationships with Indigenous peoples and help achieve coordination to address overrepresentation, both within the criminal justice system and more broadly.”

The competition closes Nov. 18.

Zinger’s report includes 18 recommendations – many aimed at improving life in prison for Black offenders whose problems, he says, mirror those of Indigenous inmates.

He’s calling for an improved drug strategy, including a “significantly revamped” prison needle exchange program, another review of the security classification process, a review of criteria that allows inmates to participate in the Mother-Child program, and for CSC to improve its connection with Indigenous and Black communities across the country.

To end Tuesday’s news conference, Zinger called the CSC an “extraordinarily well-financed” organization that should be able to correct these issues.

“If you actually crunched a number, it’s in excess of the almost $190,000 a year per incarcerated individual,” he says.

“These are phenomenal numbers, and for an organization that spends so much money to have poor correctional outcomes for Indigenous offenders as well as for Black offenders, it’s a shame and something that Canadians should be concerned with.”

TRC calls to action

In June 2015, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) issued 94 calls to action to address a number of systemic and colonial issues that have had a dire effect on Indigenous Peoples including their overrepresentation in Canada’s prisons.

The TRC said federal, provincial and territorial governments must work towards “eliminating the overrepresentation of Aboriginal people in custody” and “issue detailed annual reports that monitor and evaluate progress in doing so.”

The TRC called on the governments to also provide money to “implement and evaluate community sanctions” as an alternative to prison, and allow trial judges to “depart from mandatory minimum sentences and restrictions on the use of conditional sentences.”

With files from Kathleen Martens and Fraser Needham