Candidates in the AFN national chief election wait for the debate to begin Tuesday in Ottawa. Photo: Mark Blackburn/APTN.

Sitting in the very back row of a conference centre in downtown Ottawa, Jakob Copenace listens intently to each of the candidates vying to become the next national chief of the Assembly of First Nations (AFN) during the debate Tuesday night.

He’s one of three teenagers who travelled from Onigaming First Nation in Treaty 3 territory to take in the election.

“You should run for national chief,” he turns and whispers to his chief, and second cousin, Jeffrey Copenace.

Chief Copenace flew Jakob, 14, Niarah Kelly, 13, and Maryn Shebagegit, 14, to observe the political process – and introduce them to life outside of Onigaming. He also had a message for them – whoever they decide should be national chief, that’s who he’ll vote for.

“It was interesting to hear them talk,” says Kelly, who is experiencing her first trip to a big city. “They outlined the things that are wrong and what they’ll change.”

On stage at the other end of the convention room floor, the candidates discuss treaties, sovereignty, fighting the federal government and health care. They all claim they’re the right candidate to fix the problems.

The teens said a certain candidate “sounded genuine.”

Onigaming is an Ojibway community along the Trans Canada Highway in northwestern Ontario a little more than 100 km south of Kenora. It’s faced a number of challenges in the past couple of years including drug addiction and suicides.

For Shebagegit, there are some things she’d like to see the next national chief do.

“More healing … there’s a lot of people who I know who struggle with a lot of drinking problems,” she said. “I’d like to see more ceremonies for health.”

Onigaming isn’t alone in seeking help

Hundreds of delegates listened intently Tuesday as each candidate pleaded their case one final time before voting began Wednesday morning.

Each candidate was given 20 minutes to make a final presentation to assembled delegates followed by a question-and-answer session.

David Pratt, vice-chief of the Federation of Sovereign Indigenous Nations (FSIN) in Saskatchewan, reminded delegates of the “great history” they share in their advocacy.

He had strong words for the current federal government’s 2023 budget, saying the health care funding isn’t enough to handle the opioid crisis in Indigenous communities.

“We’ve got to stand together and send a message to governments across the country that enough is enough,” Pratt said.

According to Colter Goodwill, a band councillor for Standing Buffalo Dakota Nation an hour northeast of Regina, opioid addiction is “big” in his community.

“We really need to work together and come to some understanding of how to put a stop to that,” he said.

Other issues included natural resources, child welfare, housing and education. Pratt said they were all areas where the AFN has a duty to play a role.

Chiefs need a stronger voice to make changes that will improve the lives of community members, he added.

If Canada is serious about co-developing legislation, First Nations need to be at the table to prevent them from being in court later on, Pratt added.

“When I’m national chief, we’re going to shake this country up, and let Canada, the provinces and the territories know we’re back.”

Dean Sayers, a long time Batchewana First Nation chief, said Anishinaabe have inherent obligations dating back to when they were “lowered” into what is now known as North America.

“We are the first level of governance on these lands”, which includes the protection of land, languages, peoples and ways of life, Sayers said. The AFN is a vehicle to do that work and chiefs must be united, he added.

“I’m not going to sit in Ottawa — I’m not going to be here waiting for a meeting with the prime minister,” he said. Instead, he promised to be on the ground in communities listening to the chiefs themselves.

“We need to take action based on what we see.”

Sheila North, a veteran of past AFN leadership campaigns, took the podium wearing a brown suede jacket with beaded flower designs and a moose on the back that she said belonged to her late father.

She recalled watching him kick an “Indian agent” out of their community — a vestige of colonialism that she said still lingers inside the federal government.

North said she has learned a lot since she last sought the national chief post five years ago.

“I will tell you there are common themes across the country and I don’t need to explain them to you because you know them more than I do,” said North. “These to me are bannock and tea issues.

“I don’t give up. I’m not here because I like losing.”

North said she wants to bring a sense of unity and integrity back to the national organization.

She proposed signing a treaty with First Nations from across the country to show the federal government they’re united, and they will not support legislation designed by others that doesn’t work for them.

“Let’s make the AFN relevant again,” she pleaded.

Craig Makinaw, the former chief of Ermineskin Cree Nation and a former Alberta regional chief, said the assembly was created to ensure chiefs have a platform to advocate for First Nations.

“Our population is getting bigger, and our land-base is getting smaller,” he said of the on-reserve housing crisis that is a result of decades-long waiting lists and homes in need of major repairs.

“We need more land — everyone needs more land.”

Cindy Woodhouse, the assembly’s current regional chief for Manitoba, earned a rousing cheer when she acknowledged Wab Kinew’s election win in her province, becoming Canada’s first-ever First Nations premier.

Woodhouse recalled her experience working on the child-welfare settlement that the Federal Court finally approved in October after years of often painstaking negotiations and setbacks.

She described how at one point, when negotiations appeared to be bogging down, she took matters into her own hands: “You know what? I’m calling the Prime Minister’s Office.”

They secured the deal that night, she said. “It’s a historic amount, but it’s a historic issue.”

Woodhouse called for better First Nations policing, more communication between chiefs and the executive, and the need to lobby Ottawa more aggressively to ensure their concerns are addressed in the next federal budget.

Reginald Bellerose, chair of the Saskatchewan Indian Gaming Authority and Saskatchewan Indian Training Assessment Group, said he’s running for the top job because of “unfinished business” — the right for inherent rights and the recognition of treaties.

“We keep fighting for our rights, right until the day we die.”

Bellerose said the work being done within the assembly is “life and death,” and pleaded for chiefs to come back to the assembly. National chief elections shouldn’t be decided by a small portion of the chiefs the assembly claims to represent, he said.

He also vowed to continue advocating for First Nations should the next federal election result in a change of government.

“Canada, stop ignoring our needs,” he said.

Read More:

Attendees at special chiefs assembly in Ottawa warned they had better behave

A look at the six AFN candidates vying to become the next national chief

The election of the organization’s next national chief comes as members look for a reset, following a turbulent period when their internal politics were as high-profile as their advocacy for some 600 First Nations.

Former national chief RoseAnne Archibald was ousted in June at a special chiefs’ assembly held to address the findings of an investigation into complaints from five staff members about her conduct.

Archibald denied those allegations, and her supporters maintain she was removed from the post for trying to change the organization’s status quo.

Of the 231 chiefs who took part in the special assembly, 71 per cent voted to remove her.

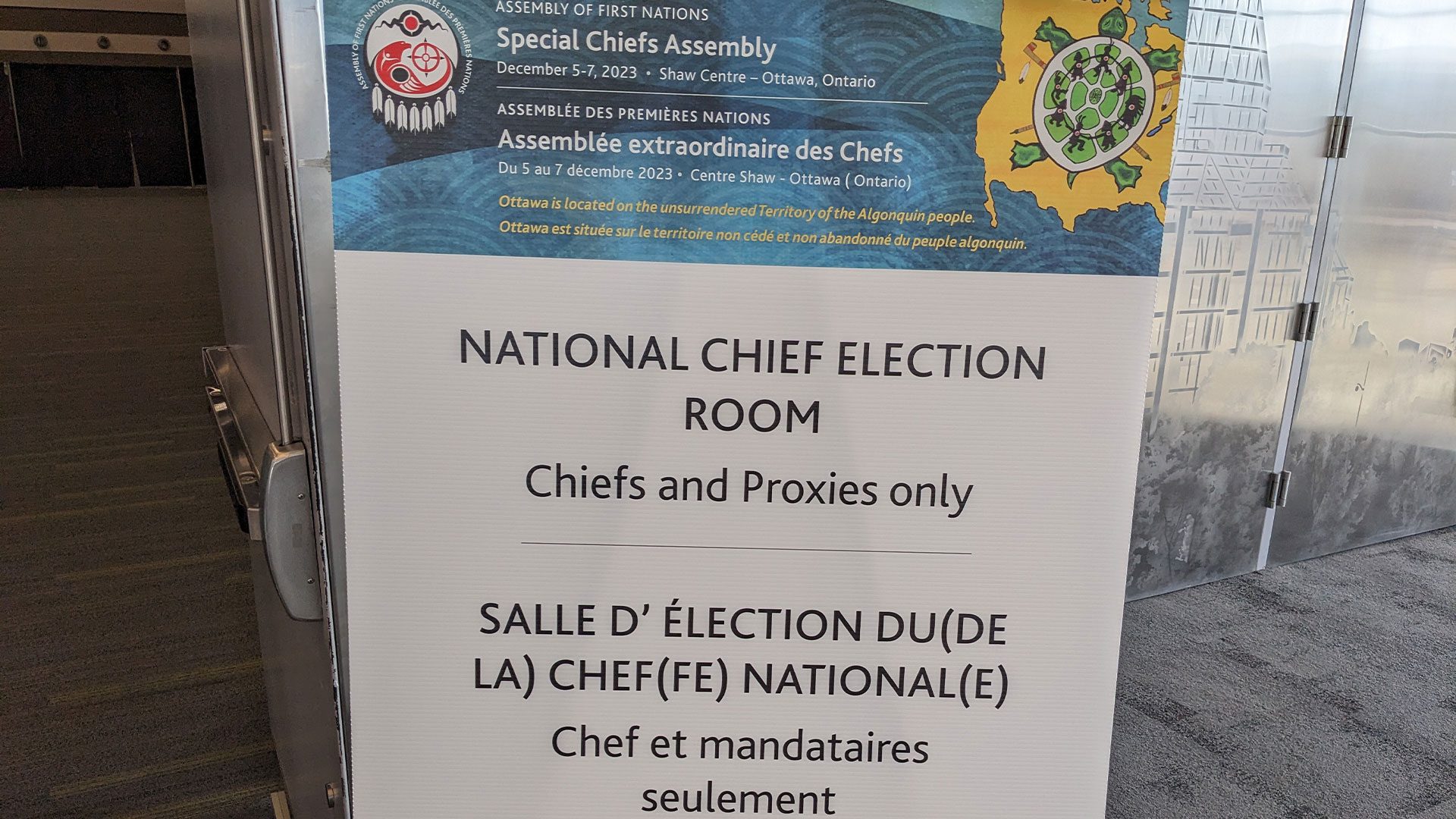

According to the assembly’s election procedures, each member nation has one vote, which can be cast either by the chief or by a registered proxy.

The winner of the election is the candidate that receives more than 60 per cent of the votes.

If no candidate receives more than 60 per cent of the vote, the candidate with the lowest number of votes is eliminated and additional rounds of voting ensue.

Immediately after the election on Wednesday evening, the new national chief is expected to participate in an oath of office ceremony.

With files from Alessia Passafiume at the Canadian Press