The Place that

Thaws

Discover the untold stories of resilience and adaptation in the High Arctic with a new six-part podcast series from APTN News called, The Place That Thaws.

Join us as we journey to Resolute Bay and Grise Fiord, Canada’s northernmost communities, where the impacts of climate change are stark.

There, a simple plan to take to the ice on a hunting trip is no longer guaranteed – and polar bears, once great hunters on the ice floes in the north, now hang around on shore.

Through intimate interviews and immersive storytelling, we bring you the voices of those on the front lines of environmental upheaval.

The Place That Thaws goes beyond the headlines, offering a nuanced exploration of how communities are confronting the challenges of a warming world.

Subscribe now on your favourite podcast platform and embark on an expedition through the frozen landscapes and resilient spirits of the High Arctic.

The estimated population of Iqaluit is just over 7,000 according to the 2021 Canadian census.

The legacy of names

Frobisher Bay is named after Sir Martin Frobisher who was the first European to visit the Northwest Passage. According to different records he kidnapped three unrelated Inuit and took them back to England. All three died before returning home. Their names differed in spelling but according to historian Kenn Harper, who writes books on the Arctic and occasional articles for Nunasiaq News, the man was named Kalicho. He met the mayor of Bristol before dying of injuries sustained by his capture. The woman was called Ignorth/Egnock and her child was Nutoic, which was probably meant to be “nutaraq” – the Inuktitut word for “child.

The territory of Nunavut turned 25 on April 1, 2024.

A dog team sits right on the outskirts of Iqaluit.

St. Jude’s Anglican Cathedral was built in the 1970s and rebuilt after a suspected arson in 2005.

Episode Five: Arctic Fever

A mobile cabin on treads. Smaller cabins are sometimes tied on to a sled frame and used by hunters when they take long trips.

We are in Resolute Bay between seasons where the ice has not frozen over enough for hunting. Devon Manik ties a sled to a boat so it will work on both water and ice.

Once he’s done tying the sled to the boat, Devon is off hunting.

Narwhal bones near the shore line. Hunters leave the bones once they have stripped away the blubber and meat. Polar bears come and snack on the rest.

Episode Four: Top of the World

We finally made it to Grise Fiord. It is 1505 KM from Iqaluit.

Almost Dark Season

It is almost dark season in Grise Fiord in late October.

The day we were there the sun had risen at 11:45 and set at 2:42. It was already dark when we arrived in the afternoon.

As you fly into the hamlet, you can see the original

townsite where the Inuit were dropped off by the Canadian government

\We arrived on November 29 at 2:12 PM. A shot of the hamlet from the plane.

Airports in the North are happy places. I watched a young father, who had given me some beef jerky during the flight greet his excited children.

The Norwegian explorer Otto Sverdrup named the location “Grise Fiord” in 1899 and it means “pig fiord”.

Jarloo Kiguyak is an event coordinator for the Hamlet of

Grise Fiord.

He has been a sergeant in the Canadian Rangers, a paleontology field technician and former mayor of the hamlet.

Larry Auduluk, who wrote “What I Remember, What I Know” spoke to us the day after we interviewed Jarloo.

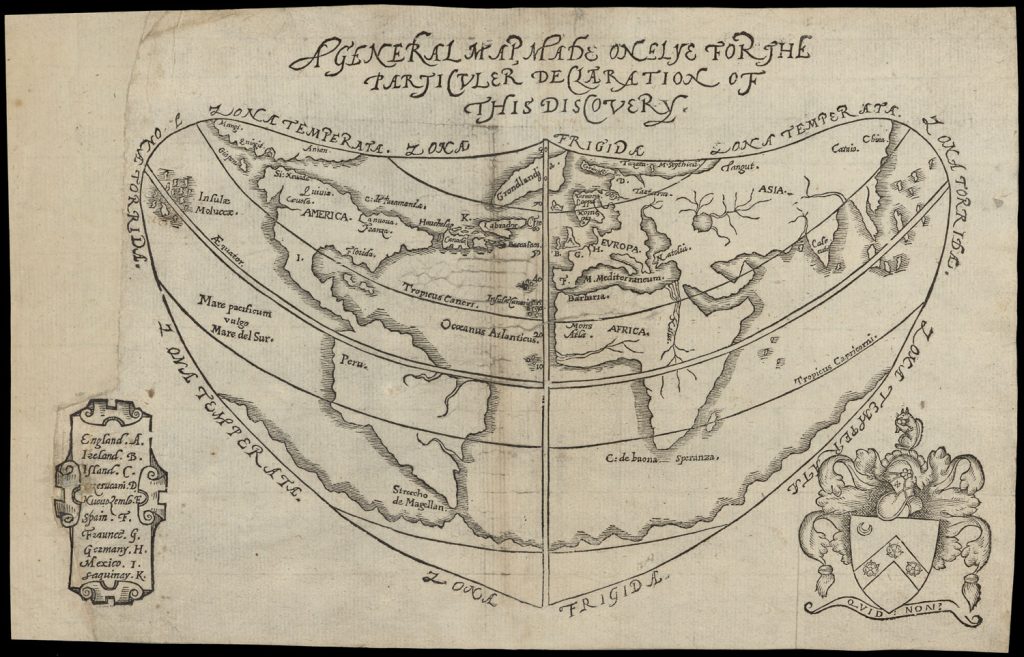

The Northwest Passage

It is such a privilege to be a storyteller. The podcast, The Place that Thaws dives deep into the issues that affect the Arctic.

This page further explores some imagery and stories of the time APTN News spent in these communities.

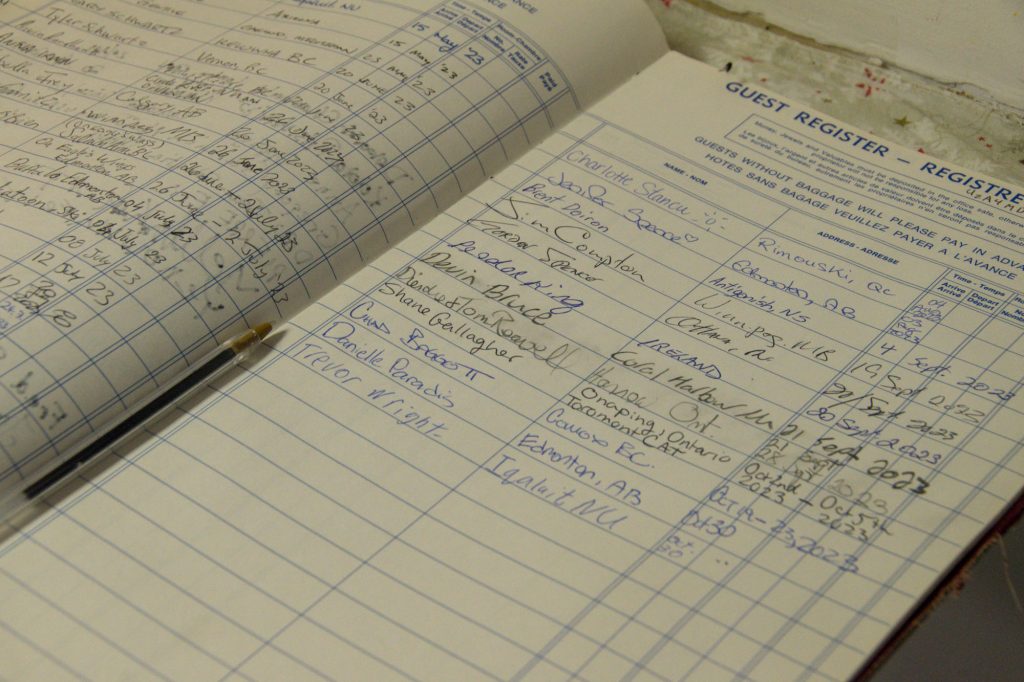

When my colleague Trevor Wright and I arrived at Resolute Bay after two days of flight travel the first thing that I noticed was the darkness. It was early afternoon and dusk was already upon us.

When we stepped off the plane we were disoriented. All around us was a vast tundra sparsely populated by snow beaten structures. Confused, we picked a path to walk and an airport worker had to yell at us that we were going the wrong way.

“We almost walked off into the Tundra,” Trevor said to me later.

Many people in Resolute Bay mentioned that the ice bergs and chunks of multi-year ice used to form a circle

around the bay that made the waters calm.

Episode Three: Arctic Post Office

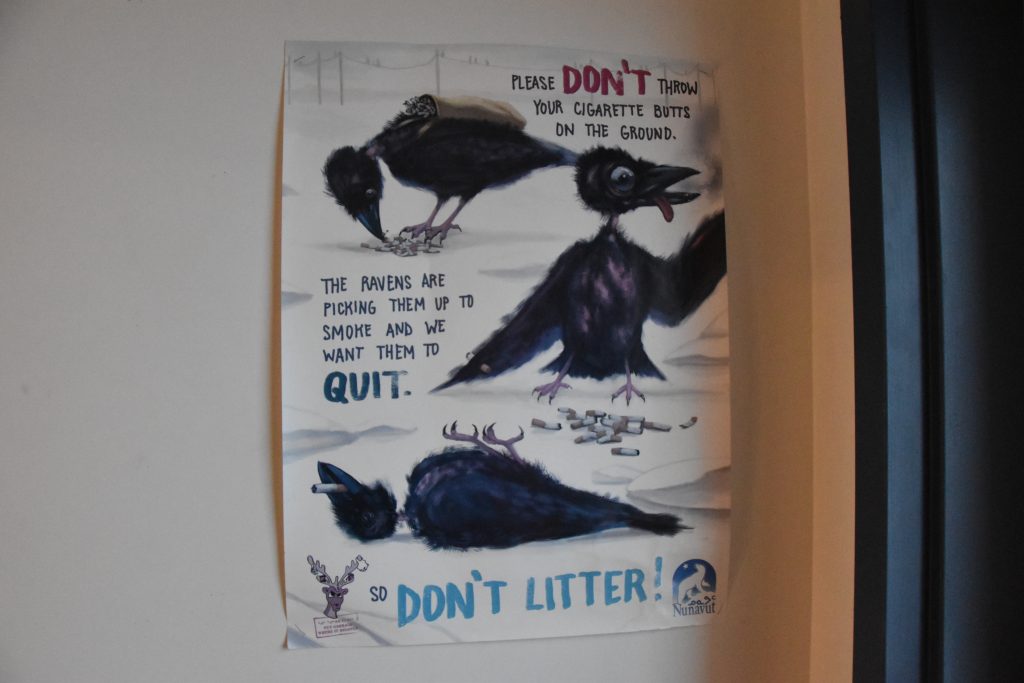

The Post Office in Resolute Bay is where I spoke with Ameela Aqiatusek about changing weather patterns and how the sun seemed to be brighter.

The Dog Sledder

Devon Manik is a twenty-two year old entrepreneur in Resolute Bay. There used to be 15 dog sleds in the community but today, he’s the only game in town. The shed is multicoloured. It looks like it was red, then painted blue and then the snowy winds scraped off the latest coat of paint.

Episode Two: The Dog Sledder

Devon Manik has a team of Inuit sled dogs. His oldest is a dog from Greenland.

The dog sled team is outside of town. The puppies stay closer to town in a fenced in area.

Devon and Divysh Purohit are looking for the wildlife officer to get a permit for Devon to sell the walrus tusks.

Episode one: Tracing one warm line

Children ride their bikes out on the ice in the bay

The tundra expands out as far as you can see. I found it was difficult for me to judge the distance of things without trees or other items I recognized as landmarks.

A ring road stretches around Resolute Bay. At certain times of day, with the fading light reflecting off the snow, it’s difficult to see where the sky ends and the land begins.

On our first day, an ATCO worker took us out to see the polar bears.

Like Churchill, Manitoba, Resolute Bay is a regular polar bear hangout. But unlike Churchill, the bears in Resolute are fat and healthy. They enjoy the leftover carcasses from local hunters. Even so, they are adapting to a changing climate. Trevor and I covered that in an article when we came home.

In the High Arctic, Resolute Bay is at the eastern entrance of the northwest passage.

It was named for the British ship, HMS Resolute, abandoned in 1850 while searching for the passage and the lost Franklin expedition, a famed explorer whose ship got stuck in the ice.

The Hamlet shares its name with the Resolute desk that adorns the Oval Office in Washington, D.C., made from oak timbers from the exploration ship.

In Resolute Bay, there’s a population of around 170 people and 83 per cent of the community is Inuit.

It’s the second most northern community in Canada – and sits on the southern shore of Cornwallis Island, way, way up above the tree line.

Unlike other Inuit communities further South, Resolute isn’t a natural Inuit settlement.

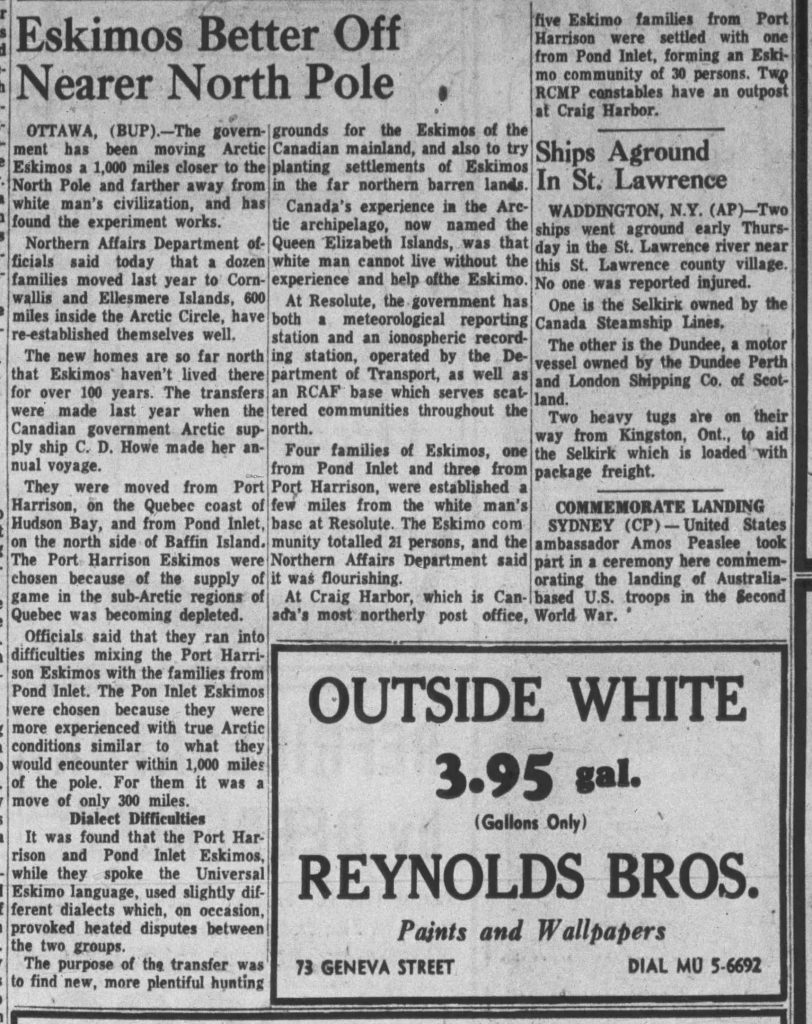

In 1953 and 1955 a group of Inuit were persuaded by the Canadian government to leave their homes in Nunavik, located in sub-Arctic Quebec, with the promises of better hunting and new homes.

The government told them if they didn’t like their new home, they could leave if they wanted to.

But, like so many promises to Indigenous Peoples, they reneged on their part of the deal.

Trevor and I met Peter Amarualik, an Inuk born in 1961 in Resolute. Peter is a hunter who works for the Qikiqtani Inuit Association, an Inuit-owned organization also known as QIA. The organization offers programs in the community as well as acting as an advocacy organization for land claims in Nunavut.

Peter’s father, Simeonie Amarualik, carved a statue in honour of the group they call the “High Arctic Exiles”.

Peter, and his wife Nancy, have lived in Resolute for nearly their whole lives. These days they notice more cruise ship traffic than they used to.

The Canadian military created a scrap metal dump to collect waste that was previously strewn around the island.

Some hunters throw leftover bones on the top of their sheds to deter polar bears from scavenging.