Sharing culture through sport

July 6, 2023

In July 2023, thousands of Indigenous athletes will journey to an area of Mi’kma’ki we now call Nova Scotia to compete in the North American Indigenous Games (NAIG).

For the Mi’kmaq, it’s a chance to showcase a vibrant culture and language.

Student journalists in the Reporting in Mi’kma’ki course – a collaboration between University of King’s College and Nova Scotia Community College – headed to Eskasoni in the lead up to the NAIG 2023.

They discovered sports is about more than a game.

It brings families together on the ballfield.

Youth and Elders share laughs and teachings as they sling arrows at the archery range.

Sports has a way of turning out role models and L’nu’k deeply committed to helping others.

Mi’kmaw archer aims to pass down traditions

By Gabrielle McLeod and Fawzi Ibrahim

Inside The Barn archery range, located just outside the Mi’kmaw community of Membertou, Unama’ki (Cape Breton), Clifford Paul prepares to shoot an arrow from his wooden, metallic-textured bow.

He closes one eye to focus, pulls back the string to the corner of his mouth and lets go. His arrow hits one of the animal targets set up at the far end of the room.

“For me, the flight of the arrow is a spiritual extension of who I am and who my ancestors were,” says Paul, a Mi’kmaw archer and archery coach. “It’s still who we are today.”

Inside The Barn archery range, located just outside the Mi’kmaw community of Membertou, Unama’ki (Cape Breton), Clifford Paul prepares to shoot an arrow from his wooden, metallic-textured bow.

He closes one eye to focus, pulls back the string to the corner of his mouth and lets go. His arrow hits one of the animal targets set up at the far end of the room.

“For me, the flight of the arrow is a spiritual extension of who I am and who my ancestors were,” says Paul, a Mi’kmaw archer and archery coach. “It’s still who we are today.”

Paul first picked up a bow when he was a young child. His older brother taught him how to make his own bow out of sticks and fishing line with arrows made using cattails.

Paul’s own children and grandchildren have taken up the sport. He says it’s important to pass on the teachings to honour the legacy of their ancestors.

“I have to teach them how to make those bows that I made when I was a kid so that they can carry that narrative,” Paul says. “The story doesn’t end with me.”

At the indoor archery range, Paul jokes around with his grandson Bryden Johnson-Julian and Addison Marshall, one of the athletes he coaches. He says these practices are about more than archery – it’s about spending time with family and friends and developing life skills.

Marshall, 15, took up archery when she was five years old. She joined Team Mi’kmaw Nova Scotia’s archery team in January and says the sport offers her a way to let out her emotions.

“If I’m mad, or if I just need to calm down, I just go outside and shoot my bow,” she says.

Marshall will compete in the North American Indigenous Games (NAIG), which will be held from July 15 to 23. More than 5,000 athletes, coaches, and staff from over 756 nations across North America will come to Nova Scotia to compete in 16 sports.

As archery coach, Paul says NAIG is a great opportunity.

“Archery is bringing us there. But that’s only part of the big picture,” he says. “These games are bringing so many kids together. It is not all competition”. There’s going to be a lot of cultural events happening.”

Paul says it’s a chance for young athletes to make new lifelong friends and honour the legacy of the Mi’kmaw archers who came before them.

“You see the superheroes are shooting bows and arrows,” he says. “This is the skill of our superheroes. Our ancestors.”

‘Godfather’ of Eskasoni basketball continues to make impact on community

By Maria Collins and Gabrielle Hill-Desjardins

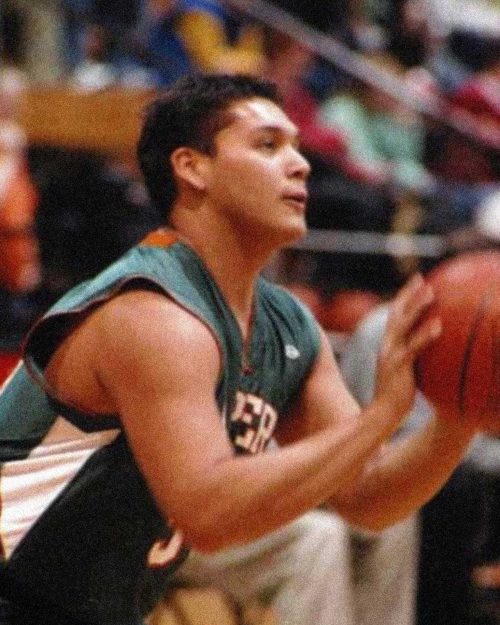

It was the summer of 1999 when 15-year-old John Denny Sylliboy started playing basketball with his friends in Eskasoni, the largest Mi’kmaw First Nation in Nova Scotia.

For Sylliboy, it was more than a game. He says he was determined to succeed early on.

“I remember watching March Madness basketball (University and college tournament in the United States) during that time and I said, ‘Jeez, I don’t see any Indigenous athletes. I’m going to be the first Mi’kmaw to play college basketball,’” Sylliboy says. “And that’s what started everything.”

By age 19, Sylliboy became the first Mi’kmaw to play at a university level on Cape Breton University’s team, the Capers, from 2003 to 2007.

Since then, Sylliboy has influenced hundreds of young basketball players and says his story illustrates the importance of sport in community.

Sylliboy found inspiration close to home. His father was the first Mi’kmaw black belt in taekwondo.

“He was so dedicated to karate, I was like ‘I want to be like my dad,’” he says. “For him to have a high degree of black belt, he has earned respect. I always wanted that too.”

And the inspiration didn’t stop there. Rita Joe, the famous Mi’kmaw poet best known for her poem I Lost My Talk, was Sylliboy’s grandmother.

“She would tell me, you know, ‘I love poetry but you love sports, and you have to remember to do it for your people,’” he says.

The now 39-year-old father of three recognizes the positive impact sport can have on young people. He credits basketball for keeping him on the right track as a teenager. Today, Sylliboy is a social worker with Mi’kmaw Family & Children Services and plays in a drumming group.

“If I wasn’t playing basketball, I think I would’ve been either on drugs, alcohol, jobless, still on welfare,” he says. “Basketball has really changed who I am.”

When he was done playing, Sylliboy moved on to coaching. He coached for over 15 years until his son was born in 2019.

Sylliboy coached Mi’kmaw athlete Hugh Paul, who says Sylliboy’s love for his community is seen in his dedication to the sport.

“He wants to see the next generation, and then the next generation move on,” says Paul. “Become better than where we were yesterday.”

Paul says Sylliboy taught him how to discover his potential, both in basketball and in life.

“For him to teach us all the things he’s taught us throughout our years, we still use that today, we still apply that to everything,” says Paul. “I’m a coach because of him.”

Paul is the assistant coach for the U16 Nova Scotia basketball team for the North American Indigenous Games (NAIG), which will be held in Nova Scotia from July 15-23.

Sylliboy says he is thrilled to see the games coming to Mi’kma’ki, what we now call Atlantic Canada, for the first time.

This year, Sylliboy will perform with his drumming group but in 2002, he attended NAIG as an athlete.

He was also the assistant coach for the U19 Nova Scotia team in 2006 and the head coach for the same age group in 2014 and 2017.

Sylliboy says his time at NAIG is one of his fondest memories and greatest accomplishments.

“Knowing that I’m part of something where there’s all athletes and they’re all Indigenous and they’re playing at a high level, it was a great thing,” he says. “It was a great feeling to be part of [NAIG].”

After years of hard work, Sylliboy has helped keep his sport alive in Eskasoni and is glad to see it thriving. He stays up to date with former athletes and takes pride in knowing they’re doing well in life.

While he’s stepped back from coaching for now, Sylliboy says he may pick it up again in a few years.

“If my son, who’s four years old now, tells me ‘Dad, we need a coach,’ I’m putting that whistle back on,” he says. “But it’s just right now, the full attention is my just family and I have no regrets.”

Sylliboy says he’s glad he got to play and coach at a high level and says the sport has “blessed” him.

“This ball here has done so much for me. It has given me the opportunity to meet new people, learn new things, travel the world. And it was all because of this,” he says, holding up a basketball.

“To this day now people look up to me like I’m the basketball godfather.”

Eskasoni teen excited for ‘once in a lifetime’ opportunity to pitch at NAIG 2023

By Gabrielle Drapeau and Christen Ferrer

Elle Gould grew up on the ballfield.

As a young child, she recalls watching her dad, cousins, aunts and uncles playing softball at Apamuek Ballfield on Shore Road in Eskasoni, a Mi’kmaw community in Unama’ki (Cape Breton).

The wide-open, dirt field is in the middle of the community, only minutes away from Elle’s house.

Now, at 17, Elle is preparing on that same field for the 10th North American Indigenous Games, (NAIG), taking place this July in Kjipuktuk (Halifax) and Millbrook First Nation.

“I’m nervous, but I’m excited at the same time,” she says. “I’m excited to meet all these new people, play against new people, see how they play softball up in different places in Canada. This is like a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.”

Elle is one of 5,000 young athletes from over 750 nations across Turtle Island (North America) who will compete at NAIG 2023. Athletes between 13 and 19 years old will compete across 16 sports.

Elle will pitch for Team Nova Scotia’s female softball team.

“You need a strong mentality. It’s very hard to be a pitcher, I find it’s hard on the mind, because the game doesn’t start until you throw the ball,” Elle says.

Elle has been training for NAIG for a long time – she was supposed to go in 2020, when the games were cancelled due to the COVID pandemic.

“That just gave me motivation to train harder for the next one,” Elle says.

Elle has played on several softball teams over the years, with young athletes from across Nova Scotia.

“You make lots of friends,” she says. “I love the sportsmanship.”

We met up with Elle and her father, Eldon Gould, at the Apamuek Ballfield on a sunny but windy day in May. They tossed a softball back and forth to beat the chill; a routine warm-up for them.

Eldon Gould has played two big roles in Elle’s softball journey – as her coach and her father.

“She grew up playing softball with the family, and we all chipped in to be teachers,” he says. “I’ve been coaching her ever since she started playing.”

“Softball has been our family sport.”

Eldon says that family and community support has been important and describes Elle as a highly motivated player and student.

“Her mind is disciplined and strong,” he says. “She’s one of those athletes that pushes herself without me telling her ‘you got to do this’ or ‘you got to do that.’ She does that on her own.”

Elle says she loves having her dad as a coach.

“That’s what makes me and my dad, me and my dad. I find sports brings us really close.”

She says she hopes to be a role model for younger kids and wants to become a coach in the future.

Eldon passed down more than softball skills to his daughter. Elle grew up speaking Mi’kmaw.

“I love our language, it’s so beautiful. I’m excited to share our culture and customs.”

NAIG athletes and spectators can visit a cultural village during the games to discover and explore Mi’kmaw culture and history.

The softball games will take place through July 17 to 22 on the Halifax Commons. Elle says she is excited to have her Eskasoni family and community come to cheer her on.

“Everything that I do, everything that anybody does, everybody will support you here.”

NAIG is the ‘Greatest opportunity’ to showcase Mi’kmaw language says teacher

By Molly MacNaughton and Ellie Enticknap-Smith

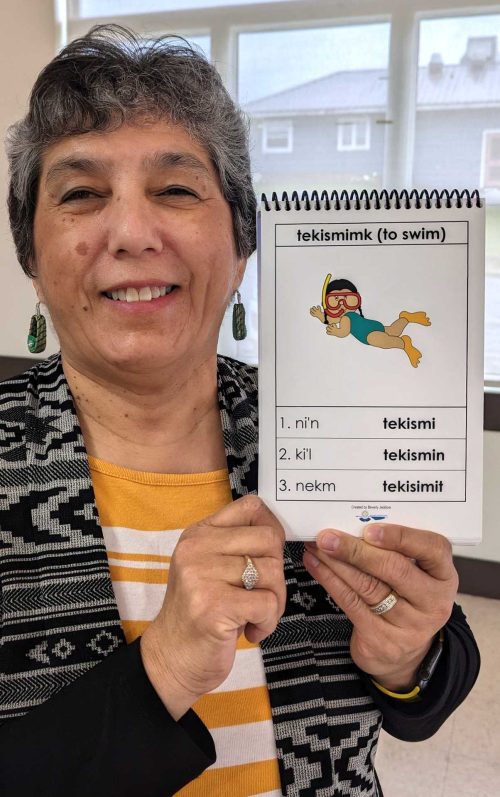

On a rainy day in late May, the countdown is on for Mi’kmaw educator Beverley Jeddore, busy getting ready for the North American Indigenous Games (NAIG) taking place in Nova Scotia.

But she’s not training for a sport – she’s translating.

Jeddore is the language lead for NAIG 2023 which runs from July 15 to 23.

“I believe that our language is a gift from our creator,” she says.

Jeddore carries a crate into the cultural centre in Eskasoni, the largest Mi’kmaw community in the world.

It’s filled with teaching supplies, the ji’kmaqn, a traditional musical instrument made from ash tree, and the Waltes, a traditional Mi’kmaw dice-and-bowl game. She holds flashcards filled with Mi’kmaw words, conjugations and pictures, all designed by Jeddore.

“When a creator gives you a gift, you must use it, you must acknowledge it, you must keep it,” she says. “And whenever you meet other people, you have to express that gift wherever you go.”

The games will bring together thousands of young athletes representing more than 756 Indigenous Nations from across Turtle Island.

“You have to ask, ‘who’s hosting this?’” she says. “The whole of Nova Scotia is L’nui’katik (the place where we speak Mi’kmaw)… so I think it’s important for us to pretty well acknowledge our people.”

NAIG is about more than just sports. This is the first time Mi’kmaw culture and language will be highlighted at the games.

“It is the greatest opportunity for our people to showcase the language, because right now, after so many hundreds of years, our language is in trouble,” she says.

Jeddore grew up near Bras d’Or Lake in Eskasoni. She works as a language technician at Mi’kmaw Kina’matnewey, a non-profit organization promoting Mi’kmaw education. Before that, she spent 28 years teaching in Eskasoni and developed a curriculum for core Mi’kmaw.

In 2018, Jeddore joined the Nova Scotia bid team for NAIG. The team travelled to Montreal to persuade the NAIG Council Board to bring the games to Mi’kma’ki. Jeddore presented the history of Mi’kmaw chants, culture and language and taught the team the traditional dance of the Mi’kmaq—the Ko’jua—to perform as part of their bid.

Afterwards, Jeddore spoke with someone who had seen their presentation.

“He said, ‘what I experienced today was the most powerful thing I have experienced in my life.’ I was blown away, I didn’t even know how to react,” Jeddore says.

At that moment, she knew they had won.

NAIG was supposed to be held in 2020, but was rescheduled because of COVID-19. The games will be the biggest sporting and cultural event to take place in Atlantic Canada.

When NAIG 2023 was announced, Jeddore and a group of Elders were asked to form a committee to translate sport-related words into Mi’kmaw like alje’maqn (baseball bat) and tekismimk (to swim).

A challenge for Jeddore is that many English words don’t exist in Mi’kmaw, making some translations complicated. She says sometimes it’s impossible to come up with the same concepts in Mi’kmaw.

“The difficulty is sometimes, you think in English. We don’t think that way,” she says.

The Mi’kmaw language is descriptive, identifying things by their purpose and activity.

Traditional Mi’kmaw sports already have names like amal-nu’tukamkewey (archery). Jeddore says the challenge lies in new sports. For example, the word “golf” was hard to name, but in the end they created alte’mamk tu’aqn.

She explains that alte’mamk means putting something in different directions and tu’aqn means ball.

Along with her own fluency, Jeddore consults different Mi’kmaw orthographies. She says her number one language resource is her Elders.

“If I were to say, for example… he’s throwing the ball, they would right away, say [eleket],” says Jeddore. “We can call and then they just tell us.”

Last year, the government of Nova Scotia recognized Mi’kmaw as the province’s first language. But the impact of colonization, including residential schools and centralization, a 1940s federal policy to relocate Mi’kmaq in Nova Scotia, have resulted in the gradual loss of the Mi’kmaw language.

“Our people started to become silent,” Jeddore says. “When I meet with another L’nu that doesn’t have the language, I want to give them something. I want to give them a word or a phrase… so that they can have it, so that they would be able to identify themselves.”

The immediate goal for the language committee is to welcome NAIG visitors in Mi’kmaw. But all their work will help keep the language alive in the long run.

“[Our ancestors] kept the language sacred,” says Jeddore. “They kept it on a silver platter, and we have that responsibility here that the next seven generations will still see and hear our Mi’kmaw language, where we’re supposed to hear it and see it.”

Musician Michael R. Denny to showcase Mi’kmaq culture at North American Indigenous Games

By Linden Thomas and María Ingrahm

Michael R. Denny recalls the magic of entering his uncle Po’pi Poulette’s basket shop when he was 11 years old to watch him create a wooden instrument the Mi’kmaq call the ji’kmaqn.

“Without that memory and [him] showing me how to do it, I wouldn’t be able to [make ji’kmaqnn],” says Denny.

Denny is a renowned Mi’kmaw musician, part of a drum group called The Stoney Bear Singers and powwow arena director from Eskasoni in Unama’ki (Cape Breton). He is also the chair of the cultural committee for the North American Indigenous Games (NAIG).

He hopes to showcase the vibrancy of Mi’kmaw culture to the thousands attending NAIG while also sustaining traditional knowledge for future generations of Mi’kmaq.

A ji’kmaqn is a traditional Mi’kmaw rattle, most notably used to keep rhythm during the Ko’jua dance. Ji’kmaqnn are made out of black or white ash trees; wood that splits easily into sections when hit with a mallet. They are traditionally made as a byproduct of basket splints.

“[The ji’kmaqn] played a big part in our identity because that doesn’t exist anywhere else,” says Denny, “It only exists here.”

Denny still has the ji’kmaqn that his uncle made when he taught him. Patched with black duct tape, this is the ji’kmaqn that Denny used when he first learned to sing Ko’jua.

The Ko’jua will be a big part of the NAIG opening ceremonies and the cultural village, which will be set up at the Halifax Commons.

For Denny, the Ko’jua embodies the spirit of both culture and sport. Denny says in traditional Ko’jua competitions, singers and dancers would perform until there was only one dancer left.

“It was a good way to show up that competition spirit,” Denny says. “It’s all within our culture.”

This is the first year that NAIG has included a cultural committee of knowledge holders, Elders, and educators. The goal is to represent sport and culture equally at the games.

As culture chair Denny wants “not only to represent the Mi’kmaw people, but to ensure that what you saw was accurate and authentic.”

The cultural committee considered setting up teepees in their cultural village, but Denny intervened, insisting they build birch bark wigwams, known in Mi’kmaw as wikuoms.

“We really wanted to draw upon the knowledge that’s still alive in Mi’kma’ki,” says Denny.

While highlighting that the event is being hosted in Mi’kma’ki, NAIG will also celebrate the diversity of Indigenous cultural traditions across Turtle Island.

There are 80 members on the cultural committee from throughout the seven districts of Mi’kma’ki as well as Inuit and Métis people.

“It’s quite a diverse group of people,” Denny says, “many different people who are recognized within their own communities.”

Denny says there will be opportunities for all Indigenous communities in attendance to perform something from their culture at the main stage each night. They will also be able to showcase crafts and traditions at the NAIG cultural village.

NAIG 2023 has been on Denny’s mind since he first got involved with the cultural committee in 2020, when the event was canceled because of the COVID-19 pandemic. It will be the largest multi-sport and cultural event ever held in Kjipuktuk (Halifax).

He says NAIG is about so much more than sports. He hopes that the cultural traditions and crafts that are showcased will continue to be practiced and celebrated by the young Mi’kmaw people that NAIG will bring together. He hopes that they will be able to heal.

“Our small nation in this little corner of North America” he says. “We exist, our language is strong, our culture is here, our culture is strong, and our young people are the same way.”