My name is Bill Isadore Deafy

This is the story of a teenage boy who doesn’t legally exist

By Kenneth Jackson and Cullen Crozier

Page created by Jesse Andrushko and Mark Blackburn

May 14, 2022 | APTN Investigates

Bill Isadore Deafy wants you to know his name.

He wants you to see his face.

See that he’s real.

Because he also wants you to know what they did to him.

And why he won’t stop fighting.

At 16.

Bill Isadore Deafy wants you to know his name.

He wants you to see his face.

See that he’s real.

Because he also wants you to know what they did to him.

And why he won’t stop fighting.

At 16.

“The whole Weechi thing is really starting to piss me off,” said Bill Deafy, who lives near Atikokan, Ont., about 250 km northwest of Thunder Bay.

By “Weechi” he means, Weechi-it-te-win Family Services, a provincially-mandated First Nation child protection agency in Ontario, known as an Indigenous Wellbeing Society.

Deafy was taken from his mother at birth and kept in several Weechi-funded foster homes.

That is until he turned 16 last October.

That’s the day Weechi kicked Deafy out of its care without knowing where he would live.

“The fact I was removed from their care on my birthday is even more upsetting. What was stopping them from making the right choice?” he said.

“If only I knew.”

It’s not like he was a bad kid.

Deafy kept a low profile living in the system.

At least he did, until October 16, 2020.

That’s the day when he first spoke to APTN Investigates about his rare Sprengel’s deformity that had festered under Weechi’s care to the point of chronic back pain and how he was having a difficult time seeing a specialist.

He blamed Weechi then, and still does, for what’s wrong with him.

And the pain is only getting worse.

“The last few days have been painful with my back,” he told APTN recently. “Simple tasks like putting on my sweater, and even just simply standing, are a struggle.”

APTN didn’t identify Deafy in 2020, instead we called him, “Daniel.”

While he was fighting to see a specialist then, he was also questioning whether he was legally in care and challenged Weechi to prove it.

He demanded, through his lawyer, all the documents that were used to keep him in care, known as customary care agreements.

Weechi provided two documents to Deafy’s lawyer, John Kingman Phillips.

First, there was a 14-day temporary agreement issued a few days after Deafy was born on Oct.29, 2005 authorizing workers to apprehend him.

The only other document Weechi provided to prove Deafy was legally in care was a band council resolution (BCR) from his biological mother’s former First Nation dated Nov. 17, 2016.

Deafy had already been in care for more than 11 years by then and, to this date, is not registered with the band.

The BCR approved paying a couple to care for Deafy for an “unspecified period” and there’s no indication as to why it was signed then.

That’s because Deafy had been living with the couple for most of his life at that point.

No one flagged this?

A boy with no agreement.

No court order placing him in care.

No one said anything?

It’s like Deafy disappeared into the First Nation child welfare system in Treaty 3 in northwestern Ontario.

It wouldn’t have been that hard.

After all, Deafy doesn’t officially exist.

His birth was never registered with the Ontario government.

Neither was his Indian status with the federal Indian registrar, and not because he wouldn’t qualify.

It was just never done.

“Weechi has failed taking care of me,” he said.

"He is doing well enough here that I do not feel that any specific orthopaedic interventions are going to be required and we will simply continue to observe him.”

Dr. Russell Clark Tweet

When Weechi dumped him from care it did so knowing Deafy didn’t have a birth certificate and his health card expired on his 16th birthday.

To renew it, he needs a birth certificate.

It also knew he never had a relationship with his biological mother. In fact, he only found out a few years ago that he has several younger siblings.

That’s why he wants you to see him.

He’s real and he’s completely stuck through no fault of his own.

He needs answers and clings to the hope that his condition can be fixed.

But he’s been waiting to see a specialist in Toronto since 2019.

“Seems as if time is running short with my back problems. If only there was a way to fix what has been done,” said Deafy.

So how did this youth end up getting kicked out of care without a birth certificate, with chronic pain from an untreated deformity and left wondering if he will ever see a specialist?

The answer to that begins with his medical records.

At least, that’s where the Ontario Provincial Police started when it launched an investigation in late 2021 following the work of APTN.

Deafy signed waivers so the OPP could access his medical records in pursuit of a negligence causing bodily harm case that is ongoing.

APTN has those records, as well.

The OPP certainly know by now that Deafy’s deformity was noticeable as a toddler because his left shoulder was lower than the right.

Deafy was referred to an orthopedic surgeon in a Thunder Bay sports medicine clinic when he was three years old by his long-time general practitioner, Dr. Sara Van Der Loo in Atikokan, Ont.

The surgeon, Dr. Russell Peter Clark wasn’t concerned about Deafy’s left shoulder in that initial screening, but mentioned the possibility of Sprengel’s, a congenital disorder.

“If he does have a bit of Sprengel’s deformity, then it certainly is quite mild and I do not think it’s going to cause any long-term problems or functional deficits,” wrote Clark, in his consultation note to Van Der Loo on Oct. 28, 2009.

“There is probably very little we need to worry about.”

A person who lived at the foster home at the time she said remembered Deafy’s shoulder condition was obvious.

“It was noticeable right away,” said Autumn Windego, 25, who was in Grade 8 when she was moved into Deafy’s foster home, so Deafy would have been about three.

“Right when looking at him as a toddler one (shoulder) was higher than the other,” said Windego.

She said she recalled Deafy loved playing sports outside during the summer but struggled because of the shoulder.

Clark saw Deafy again a few months after the initial visit when he was about four-and-a-half years old.

“He is doing well enough here that I do not feel that any specific orthopaedic interventions are going to be required and we will simply continue to observe

him,” wrote Clark.

He also sent Deafy for x-rays, which didn’t alarm Clark.

“On clinical examination, he has a full range of motion of both arms, a little better coordination I see, on the right side than the left with his arm movement,” wrote Clark.

Deafy started to complain about pain in his back a few years later and Van Der Loo made another referral to Clark, at least that’s what it says in Deafy’s medical records.

However, there’s no record of that meeting with Clark ever happening. In fact, Deafy’s medical records have an unexplained gap of five years after this missed referral.

There are years of missed annual medicals, required by law for children in care.

When he did have a medical, Deafy was given a clean bill of health and his deformity was never mentioned.

That is until Deafy got a new foster mom at age 14.

She was asking a lot of questions about the type of care he was receiving from Weechi.

Van Der Loo sent Deafy back to Clark.

“I saw Bill today with his foster mom,” wrote Clark on Sept. 18, 2019. “He has a Sprengel deformity of his left shoulder.”

Deafy’s elevation of his arms went from 160/180 degrees, as a young child, to 135/180 in the left and right arms, respectively.

Deafy told APTN he had basically stopped using his left arm around this time.

Clark ordered a slew of tests.

X-rays, CT scan, MRI and ultrasound, the latter of the three having never been done before.

Deafy was also pushing for surgery at this consultation with Clark.

“With respect to doing surgical management for this, this is an uncommon procedure and traveling to [The Hospital for Sick Children] most likely is the best way of managing this,” Clark wrote to Van Der Loo.

But no referral was made to SickKids in Toronto by Clark or Van Der Loo following that consultation.

The MRI, however, confirmed “a classic finding” of Sprengel’s.

By June 2020, Deafy is back at Clark’s office in Thunder Bay but still no referral has been sent to SickKids.

Following his examination of Deafy, Clark wrote Van Der Loo that he first saw him at the age “4 or 5.”

“He had minimal deformity [then],” said Clark. “The question would be still at the age of 14 if there is any benefit to him having the Green-Woodward procedure. The procedure is generally done at the age of 9-18 months and was done as late as 3 or 4 years of age and at all times since I have seen him in consult, he has been outside the age typically where we would consider surgery.”

Clark first saw Deafy the day before his fourth birthday and a quick internet search shows that while surgery is usually done at a young age, it’s not always the case.

And this medical paper looks at the cases of two adults with Sprengel’s, which the researchers found uncommon.

“Most patients with Sprengel’s deformity receive surgical treatment as a child or adolescent. Thus, it is uncommon to identify an adult with untreated Sprengel’s deformity,” the researchers wrote.

Clark also admitted in his letter to Van Der Loo that he has no experience in this type of deformity, nor does anyone in Thunder Bay.

“This is a very rare condition with no experience surgically locally and therefore, a visit to Sick Kids would be appropriate for assessment,” wrote Clark.

“But again, given that he has fallen outside of the typical age group for surgical management for this, I am not sure that they would consider him a candidate at this age to go ahead with a Green-Woodward procedure. But if so, that could be undertaken in Toronto.”

APTN couldn’t find any reference online of a “Green-Woodward” procedure. That’s because it appears they are two separate procedures to treat Sprengel’s with Woodward being the more cited procedure among medical papers.

Clark didn’t make a referral to SickKids after this consultation.

Van Der Loo didn’t either, despite it being all Deafy wanted for almost a year.

So, he waited.

And waited, but nothing came.

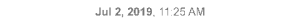

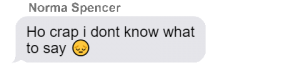

Then he was back for another telephone consultation with Clark on Jan. 7, 2021. The call was made along with Deafy’s foster mom, Sarah Laurich, who asked if a referral had been made.

“Umm, I am almost positive that is done here. But I am not sure if it was done by me or done by somebody else.

Let me just check the notes here,” Clark is heard saying in an audio recording of that call.

Clark later said he believed Van Der Loo was supposed to do it.

“The last thing I have is something about a lawsuit that was sent to us about him,” said Clark. “This is through APTN. They were doing investigative reporting about his case.”

The stories never mentioned a lawsuit – Deafy just wanted to be seen by a proper specialist.

“Yeah, but, again, what happens is these red flags fly up from the CMPA and that’s like ‘do not do anything else. Do no not touch anything else or go forward,'” Clark is heard saying on a recording of the telephone call.

The CMPA is the Canadian Medical Protection Association, which provides assistance to medical professionals when legal issues arise.

Clark went on to say “someone dropped off a package at the hospital” which were the APTN stories.

“If you are telling me that Dr. Van Der Loo told you that she is expecting us to make the referral we can do that as of today,” said Clark.

“Bill is a very specific individual and has a very specific and rare problem. We have to listen to what the specialist at SickKids says.”

Deafy and Laurich hung up and waited, again.

For more than a year he didn’t hear from anyone.

So Laurich started calling around beginning with Clark’s office but couldn’t reach anyone on Jan. 12, 2022.

She then tried Sick Kids in Toronto who told her the referral was made the day before but Clark’s office made the referral to a children’s hospital in Ottawa, according to a recording of that call.

It was immediately declined because it was the wrong hospital, again, according to a call between the foster mom and someone from the Ottawa hospital.

Clark’s office promised to resend the referral to SickKids.

Deafy was finally contacted by an orthopedic surgeon at SickKids near the end of last March.

But his excitement didn’t last long.

The surgeon referred Deafy to get x-rays for scoliosis.

Deafy was livid.

“When I saw the referral, I was shocked to see that the doctor has identified my Sprengel’s as scoliosis, like what?” said Deafy.

“I’ve waited so fricking long just to find out he put scoliosis.”

“Is it only in my wildest of dreams where they finally do their job and things that needed to be done were actually done?”

Bill Isadore Deafy Tweet

When Weechi kicked Deafy out of care last October it never said anything to him.

Not a phone call or email.

He found out on his birthday from Laurich because Weechi sent her a letter the same day saying her house was no longer approved as a foster home.

“So they said the home they put me in isn’t safe but just left me there?” said Deafy.

Weechi also sent a letter to his biological mother saying Deafy was her responsibility now, but they have no relationship.

Deafy first moved into Sarah and Dave Laurich’s home in 2018 for what was supposed to be a short stay.

But when it was time for Deafy to go back to the foster home he had lived in most of his life, he flat out refused.

He never gave a reason why he didn’t want to go back but he did tell APTN the Laurich’s were his family now and his forever home.

So when Weechi cut off his funding and resources the Laurich’s didn’t kick Deafy out, especially not on his 16th birthday.

He’s part of the family.

Only unlike most moms, Sarah can’t simply renew Deafy’s health card because he doesn’t have his birth certificate, something needed once you turn 16.

Laurie Rose is the executive director of Weechi.

She was also Deafy’s legal guardian for many years.

In Weechi’s letter to Sarah Laurich, Rose blames her for interfering with Deafy getting his identification, missing appointments and not living up to the standard of care expected of foster parents.

“Your inappropriate conduct and non-communication compel the removal of your designation and that of your home,” said Rose.

“You have outright ignored your obligations … especially the best interest of this child.”

The letter shocked Sarah and her lawyer.

“I draw your attention to my letter dated August 17, 2021, wherein I ask for Weechi’s assistance in obtaining these documents on behalf of Bill. It simply defies logic that my client would ask for Weechi’s help and then sabotage any attempts made on his behalf,” wrote Julia Tremain, of Waddell Phillips in Toronto, in a letter to Weechi last November.

Weechi had been saying for several months before kicking Deafy out of its care that it needed his biological mother’s signature in order to get his birth certificate.

It’s simply not true, according to the Ontario government.

“If the child is in the legal custody or care and control of a children’s aid society (CAS), including Indigenous children’s aid society’s, and the parents are unable to certify the birth, the birth may be certified by the CAS if they provide proof of custody,” said Ellen Samek, spokesperson for the ministry of government and consumer services.

“The CAS would provide a letter signed by its executive director stating that the CAS have care and custody of the child pursuant to a temporary care agreement or have a court order placing the child in.”

Weechi’s letter was also shocking because for several years Sarah had to chase Deafy’s workers for information on medical appointments, deal with showing up unannounced at his school and not responding to his emails, in particular several emails where he asks to see his file and to have his rights, as a youth in care, respected.

Sarah also kept voluminous records of her interactions with Weechi.

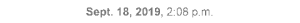

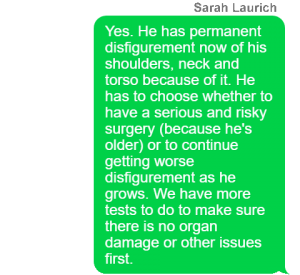

This includes an extensive timeline of recorded telephone calls and text messages between Laurich and Deafy’s child protection workers.

She provided this information to APTN.

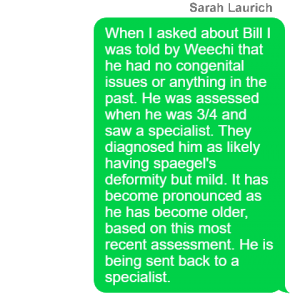

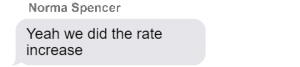

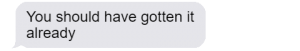

One of the things that stands out is how Weechi claimed to not know about Deafy’s deformity.

It begins with a text message in June, 2019.

Spencer knew of his older brother have scoliosis, which is also confirmed in one of Clark’s notes because he was also the doctor for that youth.

Sarah wrote again on Sept. 19, 2019 that they have to do all sort of tests now and that Deafy has to go to SickKids.

This exchange of texts was first reported by APTN in October, 2020 and the timeline of text messages show Sarah pushing Weechi for meetings, approvals and help with getting Deafy treatment almost from the moment he arrived at her home.

As for Deafy, he wanted this story told because he never felt seen with Weechi.

“Is it only in my wildest of dreams where they finally do their job and things that needed to be done were actually done?” he said. “It could be as easy as I don’t care, but I do care.”

That’s the emotional pain of being under Weechi for 16 years.

Then there’s the physical.

The pain started in his back with his left shoulder blade, but now he feels it in the middle of his back, his left arm “some days is so friggen sore” and some days it feels like his legs aren’t attached to him.

“Scary stuff,” he said.

Neither Weechi or Clark responded to questions from APTN.

Bill Isadore Deafy wants you know…

He went through this because there are other children and youth out there like him across Treaty 3.

APTN has discovered several children who are in care with no legal agreement, or with expired agreements, and without any sort of identification.

It was reported in early 2020 that a former Crown ward aged out of care a week before the global coronavirus pandemic began without a health and SIN card.

His monthly funding was returned soon after APTN wrote to his workers.

We also wrote someone else: Laurie Rose, because the agency was Weechi.

There’s other lost children of Treaty 3 out there.

Their stories will be told one day soon.