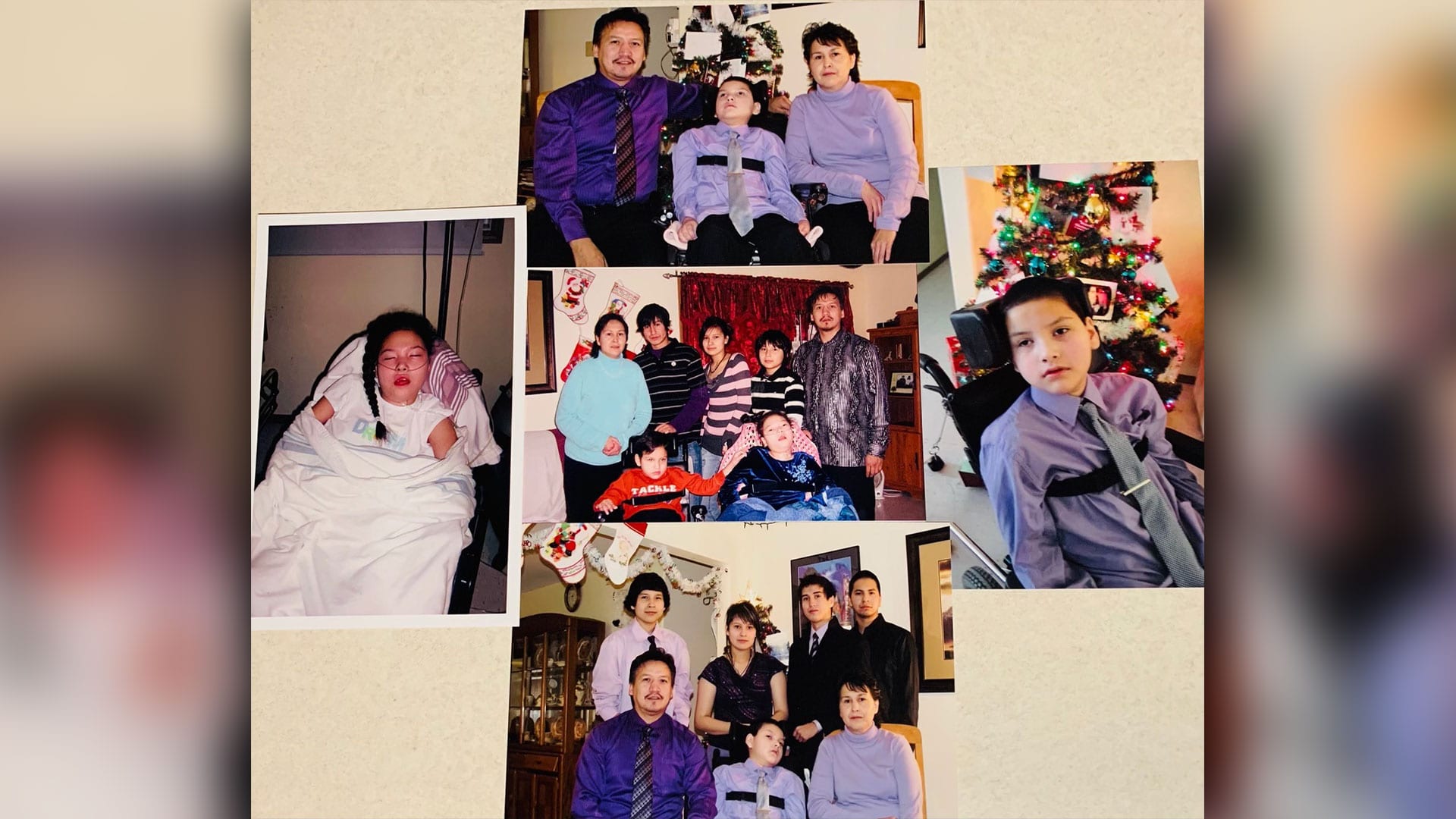

Zach, Veronica, Sanaye and Jacob Trout in an undated picture. Photo courtesy: Trout family

Zach Trout hesitates to use the word “nightmare” to describe the ordeal his family went through, but it’s the word he keeps coming back to.

He and his wife Veronica struggled for 13 years to care round the clock for two of their children, Sanaye and Jacob, who both had complex medical needs.

“I can’t say nightmare because I love my kids,” says Trout, 50, from Cross Lake First Nation in northern Manitoba. “It was my duty to care and provide for the kids.”

They both had Batten disease, a rare genetic neurological disorder that normally begins in early childhood. It results in seizures, vision loss, deterioration of motor skills, cognitive impairment and, eventually, death.

Sanaye and Jacob started showing symptoms in infancy.

From then on, every day was an uphill fight to get them what they needed.

“We exhausted our funds throughout that process, and there was no resources available for us as Indigenous people. Everything that we had, we had to fight for tooth and nail,” says Trout. “I had to argue my way through things, and I had to fight through things by arguing with harsh words.”

They would spend weeks, even months, at a time at hospitals in cities because their remote Cree community didn’t have adequate resources, just a nursing station.

“A Band-Aid solution,” in his words.

They had to pay for hotels and bring their other kids to visit while away.

He and his wife eventually quit their jobs.

They took turns sleeping as the kids’ symptoms started needing 24-hour care.

“It’s a nightmare for a family to go through that,” he says, “and there’s nothing that you can do. All you can do is just provide the best care that you can as a parent — and watch your children slowly deteriorate.”

Sanaye and Jacob both died from their disease before age 10.

Trout’s voice quivers with emotion as he recalls the frustration, sorrow and trauma.

“Still today, I cry every now and then, knowing all the suffering that they went through,” Trout says. “Even my wife, I still see her and catch her crying in our room, knowing that they’re gone and we won’t see them.

“And all we ever tried to do is to provide the best care, even though it was pretty hard. But we did what we had to do by not giving up. We will not give up.”

He’s still fighting — but now it’s for justice.

Trout is the latest proposed lead plaintiff in a $10-billion class action filed in 2019 by Xavier Moushoom and soon joined by Jeremy Meawasige, the Assembly of First Nations and several others.

They are suing the Crown over its wilful underfunding of child and family services on reserves and in the Yukon as well as its refusal to implement Jordan’s Principle between 1991 and now.

Read More:

Jordan’s Principle is a legal rule that exists to ensure First Nations kids receive essential services without delay or denial due to bureaucratic inertia or jurisdictional disputes. It was adopted by Parliament in 2007.

Trout represents the families of kids who suffered or died between 1991 and 2007 while awaiting services the Crown was obligated to provide.

He calls them “the forgotten children.”

And he wants to be their voice.

Trout seeks $1 billion in damages for negligence and breach of fiduciary duty plus $50 million in punitive damages from the federal government on their behalf.

He alleges the Crown discriminated against his family and breached their charter right to equality under the law by refusing to pay for products and services Jacob and Sanaye desperately needed.

Jordan’s Principle was named after young Jordan River Anderson, who was also Cree from Manitoba with a story similar to Sanaye and Jacob’s.

Born in 1999, Jordan’s family soon surrendered him into provincial care due to a lack of services on reserve.

Doctors said he could move to a specialized foster home when he was two, but Manitoba and Ottawa couldn’t agree on who would pay the cost of allowing him to be at home.

The governments were still bickering when Jordan died in 2005, at age five, having spent his entire life in hospital.

Sanaye was born in 1998, while Jacob was born in 2002.

“Despite their conditions and dire need for medical attention, Sanaye and Jacob fell within a jurisdictional gap between the Province of Manitoba and the Crown,” alleges Trout’s statement of claim.

“Health officials gave the family only six syringes per month for Sanaye, even though she needed to receive six injections a day. The family had to reuse these syringes, causing infections and more seizures,” the claim says.

“The family was given two feeding bags per month to feed their children four times a day. They had to reuse the bags, which caused more problems with bacteria and infections. Likewise, the Crown refused for more than a year to provide inclined beds that Jacob and Sanaye needed at home, causing them sleep problems and more seizures.”

The allegations have not been tried in court, and Ottawa has filed no defence materials.

However, the Crown believes it isn’t legally liable for their suffering and “owes no duty to compensate” the Trout family because Jordan’s Principle didn’t exist yet, according to documents the plaintiffs filed in April.

“The Crown maintains that Jordan’s Principle did not become actionable until Parliament passed a resolution formally recognizing it,” lawyers write.

“Therefore, the Crown asserts, a claim on behalf of the 1991 to 2007 Jordan’s Principle class should not be certified, and the Crown is not prepared to mediate those claims. The Crown wishes to advance its defence in court in respect of those claims.”

Seven months before this document was filed, Canada issued a statement on the “certification of claims” put forward by the class action.

“Parties are all in agreement concerning the certification of the claims put forward by the AFN and the Moushoom class counsel, including the certification of a Jordan’s Principle class beginning in 2007,” the government said. “We are making progress in negotiations.”

What the government didn’t say is that it would only consent to certify if the pre-2007 Jordan’s Principle class — Trout and potentially thousands of people like him — was excluded from the talks.

The lawyers disagreed with Canada. But, since they can’t force the Crown to mediate claims it wants to fight, class counsel split the claim in two.

While victims of the child welfare system and some of the Jordan’s Principle victims are currently in mediated settlement talks, Trout prepares to fight in court for the others.

“The Crown knew or ought to have known for decades that its policies were wholly insufficient for the provision of essential services and products to the class members,” his claim argues.

“The child class members were vulnerable children at the mercy of the Crown for services. The Crown knew or ought to have known that its policies and practices were having a devastating impact.”

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and Indigenous Services Minister Marc Miller have indicated several times they plan to compensate victims of the child welfare system.

But they’ve declined to explain why they want Trout and families like his to litigate, despite being asked by APTN News multiple times.

Miller again declined to explain their position or offer a message to the families when asked Wednesday.

“Any of those discussions between us and the parties in question I’m not going to use a public platform to discuss at this time,” he says.

Trout tells APTN the behaviour of the Canadian government appalls him. He’s upset they continue to fight.

“I am ashamed of the government today,” he says. “I will still continue to be ashamed of the government today and for the future until they roll up their sleeves and say, ‘OK, we have done something wrong. We have failed the Indigenous people — and especially the children that needed help’.”

He says he only wants the case to help other kids the system has hurt.

“I want to open the doors for the future generation, (so) that they don’t have to go through this,” he says. “Because we are the foundation of this country. We are the pillars of the country, but we are forgotten people.”

Government officials told APTN last month “any number of outcomes are possible” when Trout’s contested certification hearing finally rolls around.

No date for it has been set.

The Canadian Human Rights Tribunal ordered Canada to properly implement Jordan’s Principle in 2016, after the tribunal concluded the state was violating basic human rights by not doing so.

Hundreds of thousands of requests have been approved since then.

Read the statement of claim: