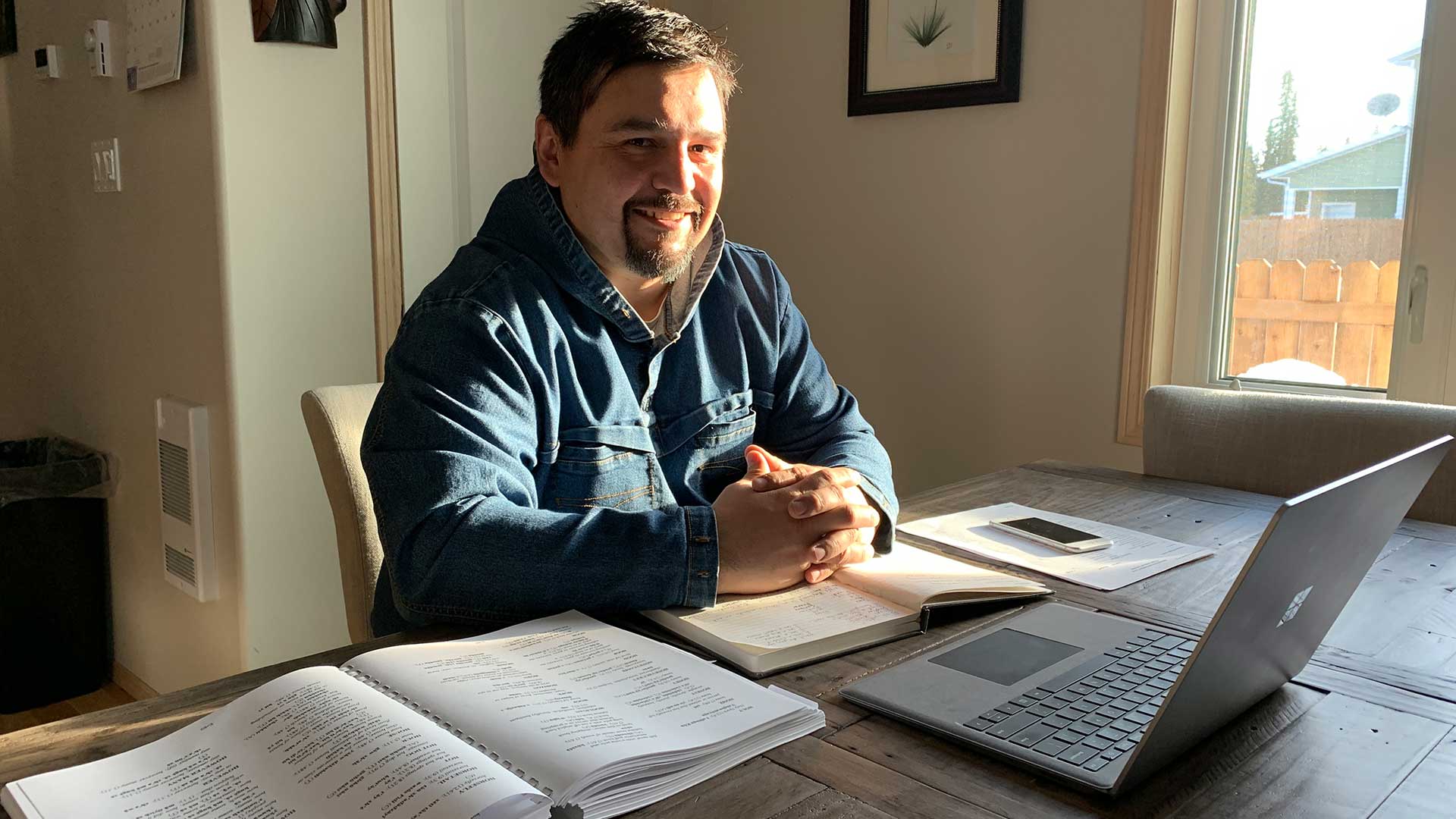

For two hours a day, three days a week, Gus Morberg attends his language class over Zoom.

As a citizen of Teslin Tlingit Council, a First Nation in the Yukon, Morberg, 40, is just learning to speak his ancestral language of Tlingit.

Along with about a dozen other adult students, each week Morberg learns speaking, vocabulary and pronunciation from an instructor at the Yukon Native Language Centre (YNLC).

While he’s only been in class for six weeks, Morberg has made impressive progress, and can even sing a song and recite the class’s language prayer in Tlingit by heart.

“It feels really good, it feels wonderful to learn my language,” he told APTN News.

“I’m reclaiming my true identity as a Tlingit man, and making myself feel whole as a person.”

A stolen language

Like most First Nations people in the Yukon, Morberg never learned his language.

Despite his grandmother being a fluent speaker, Morberg said she only passed down a few words and phrases to her own children.

Morberg said his grandmother, a residential school survivor, was a “silent speaker,” meaning trauma and shame prevented her from speaking her language.

“It was taken from us by residential schools and later literally stolen from us,” he said. “It doesn’t feel good.

“Our elders felt shamed speaking the language so they were reluctant to share it with us.”

Morberg said the only time he ever heard his grandmother speak Tlingit fluently was during her final days in palliative care.

“She defaulted back to the language. We had to have translators in the room for her and she was talking to her ancestors, her brothers, her sisters, her mom and dad; it was like they were right in the room with her.”

While the episode was painful to witness, Morberg said it also roused an interest in him to learn what should be his mother tongue.

“Ever since then that planted the seed in me to learn my language, because it’s that there that told me it’s our pathway to the spirit world and to our ancestors.”

Indigenous Languages on the brink of extinction

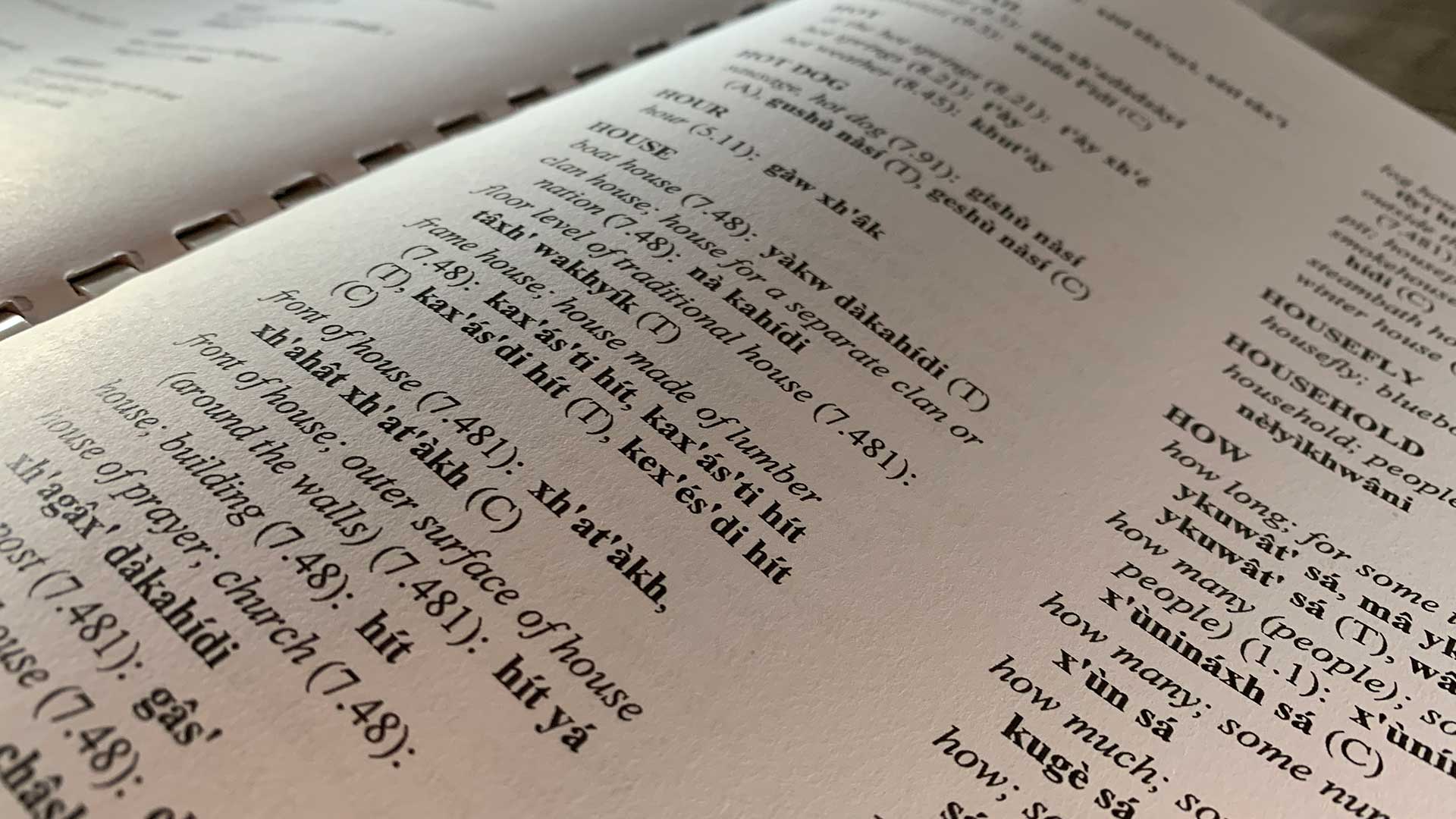

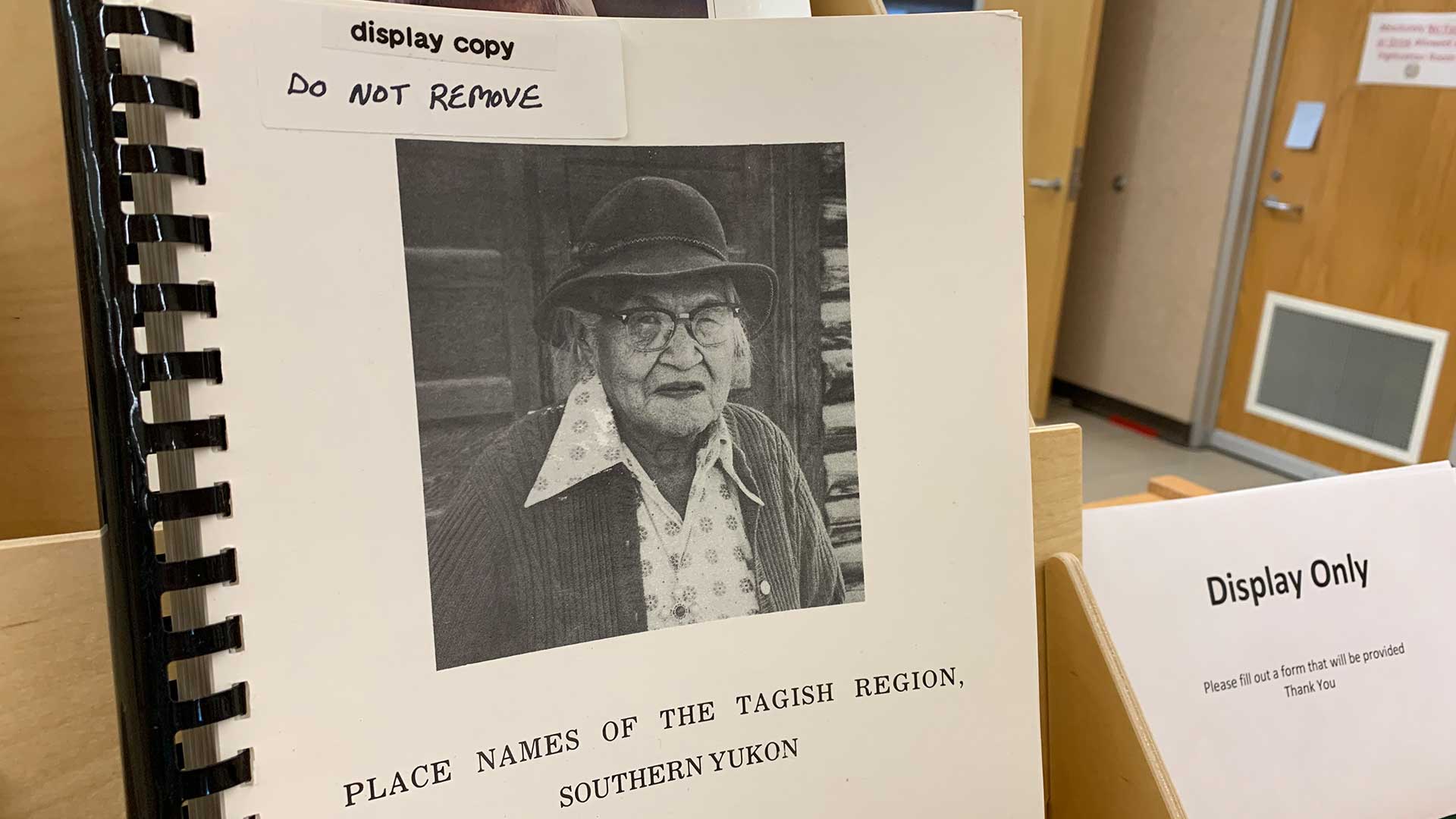

There are eight Indigenous languages in the Yukon.

According to the YNLC’s website, seven of these languages, Gwich’in, Hän, Kaska, Northern Tutchone, Southern Tutchone, Tagish, and Upper Tanana “are from the Athapaskan family which spreads from central Alaska through northwestern Canada to Hudson Bay.”

While Tlingit is distantly related to the Athapaskan family, it’s spoken mainly along the southwest Alaskan coast and in parts of B.C. and southern Yukon.

Once thriving, Indigenous languages spoken well into the 1930s, now all of them are disappearing.

Dan Tlen is a Yukon languages linguist and a Southern Tutchone instructor at the YNLC.

He said there’s now probably less than 20 speakers for all eight languages.

“Most of the elders have died off. They were the ones who were fluent speakers. I don’t think there is one community in the Yukon that’s not in trouble.”

A time before English

Prior to the 1930s, English was not widely spoken in the Yukon.

While some First Nations people did come in contact with the language due to interactions with fur traders, missionaries and outsiders during the Klondike Gold Rush of 1897-1899, the majority of the territory was not influenced by English speakers.

As a result, traditional languages and a First Nations’ way of life was maintained well into the 1930s due to the territory’s remoteness and isolation from southern Canada.

Lizzie Hall is a Selkirk First Nation elder and a Northern Tutchone speaker.

At 85 years old she can still remember a time when the only language she had ever heard was Northern Tutchone.

It’s a time she remembers fondly.

“It was really good. People might think it’s hard to live in the bush, but it was beautiful because everybody treats each other really good and they look after one another,” she said.

“It takes a whole community to raise a child, and that’s how I was raised.”

But life for Hall, and most other First Nations children, changed forever with the construction of the Alaska Highway.

Prompted by the attack of Pearl Harbor in 1941 and combined with Japanese threats to the west coast of North America, the U.S. government began construction of the highway in 1942 in order to connect Alaska with the lower 48 states.

The Canadian government agreed to the highway as long as costs associated with it were paid by the U.S.

Not only did the highway allow for easier travel to and from Alaska, but also more efficient travel within the territory.

Consequently, church missionaries intent on assimilating Indigenous children into Euro-Canadian culture now had easier access to communities that had previously been relatively isolated, and during the 1940s First Nations began being sent en masse to residential schools.

Memories of residential school

Hall can still remember the day she was taken to residential school at 12 years old.

Raised mainly by her grandparents, Hall was staying with them in a tent in the bush with her baby sister during the time she was taken.

Over seven decades later, she can still remember how policeman barged into the tent one evening and demanded she come with him, or else he would take her baby sister and throw her grandparents in jail.

“My grandma and grandpa say, ‘No, we don’t want her to, we don’t want you to take her to school.’ And my grandpa grabbed me on the other side with my grandma. They were pulling me either way,” she recalled, tugging on her sleeve.

“I talk to them in Indian to my grandma and grandpa, I said, ‘Just let me go, I’m old enough. I’ll look after myself.’”

Despite it being freezing cold outside, Hall was taken from her family with just the clothes on her back. She remembers being driven by toboggan in the cold for several miles to police barracks. A few days later she was put on a plane by herself and sent to a residential school in Carcross, 70 km south of Whitehorse.

Upon arriving at the school, Hall was met by her older sister and the principal.

“I went to my sister and I start talking Indian to her and she squashed my hand like this,” Hall said, grabbing her wrist.

“She told the principal standing there, ‘My sister wants to go to washroom.’ That’s how she explained things to me in the bathroom, and she told me that ‘if you speak your language they’re gonna strap you.’ And I got scared.”

Though Hall was practically a teenager and had no idea how to speak English, she quickly learned the consequences of speaking Northern Tutchone around school staff.

“If they catch you speaking your language, they don’t speak or nothin’ to you, they just grab your hand and take you into the office and you get strappin’,” she said slapping her hands hard together.

“One time they even got a big thick strap and hit my thumb right here,” she said holding out her thumb.

“It was out of joint and they just grab it and push it back,” she said pulling it sharply to the side.

“I just hurt.”

Read More on Indigenous Languages

Canada unveils Indigenous Languages bill to fanfare, criticism

Senate passes Indigenous Languages bill with amendments addressing Inuit concerns

Tlen, who is also a residential school survivor, said another way the schools eradicated language was shame.

“Even though it might not seem overt, we were indoctrinated to think that our parents lived in inferior surroundings,” he said.

“They didn’t have running water, they didn’t have indoor toilets. In that way they kind of indoctrinated young people to think that their parents and grandparents were inferior, which probably contributed to them not wanting to learn the language.”

Just as the school’s abusive methods intended, residential school survivors began to speak English as their main language.

Hall said while it was difficult for her to learn a new language at 12 years old, she eventually adapted and for a time almost forgot how to speak Northern Tutchone.

“I could hear it but I couldn’t speak it when I went home for holidays and things like that. When I tried to speak, I speak funny, so I was ashamed to speak thinking people will laugh at me.”

However, an incident in which she spoke English to her grandmother caused her to want to relearn her mother tongue.

“She said, ‘You look take a look at yourself,’” in her language. ‘You take a good look at yourself. You look at the colour of your face before you talk to me like that,’ she told me. This is true. I got stuck between the white people and Native people, I was stuck in between.”

She said she’s now one of the lucky ones.

“I was downloaded!,” she said with a laugh.

“That’s one thing they can’t take away from me was the language, I’ll never forget it. But these kids who were taken four years old, five years old. They don’t have a clue what our language is when they come back.”

Devastating consequences

The effects residential and day schools had on Indigenous language transition are still felt today.

According to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC), many of the almost 90 surviving Aboriginal languages in Canada are under serious threat of extinction.

The consequences of language loss can also trickle down to the next generations who didn’t attend residential schools.

A joint study by the University of Oxford, the University of British Columbia and the University of Victoria found Indigenous communities that had low numbers of language speakers reported six times the number of youth suicides compared to communities with many speakers.

Hall said she’s seen the destruction caused by language and cultural loss first hand.

“We didn’t learn (right or wrong). All we know is wrong. We didn’t know how to be right,” she said.

“These people that went to school young can’t teach their children because they only know that way, white man’s way, and so they can’t teach their children. I see lots of change and the family ain’t close like it used to be when I was raised.”

Push to bring Indigenous languages back

Now, work is being done to boost the number of language speakers in the territory.

Most First Nations in the Yukon have developed their own language revitalization programs which have yielded promising results.

In September, Liard First Nation’s language department was awarded The Council of the Federation Annual Literacy Award for its work to document the Kaska language by making recordings and transcriptions, as well as collecting traditional knowledge.

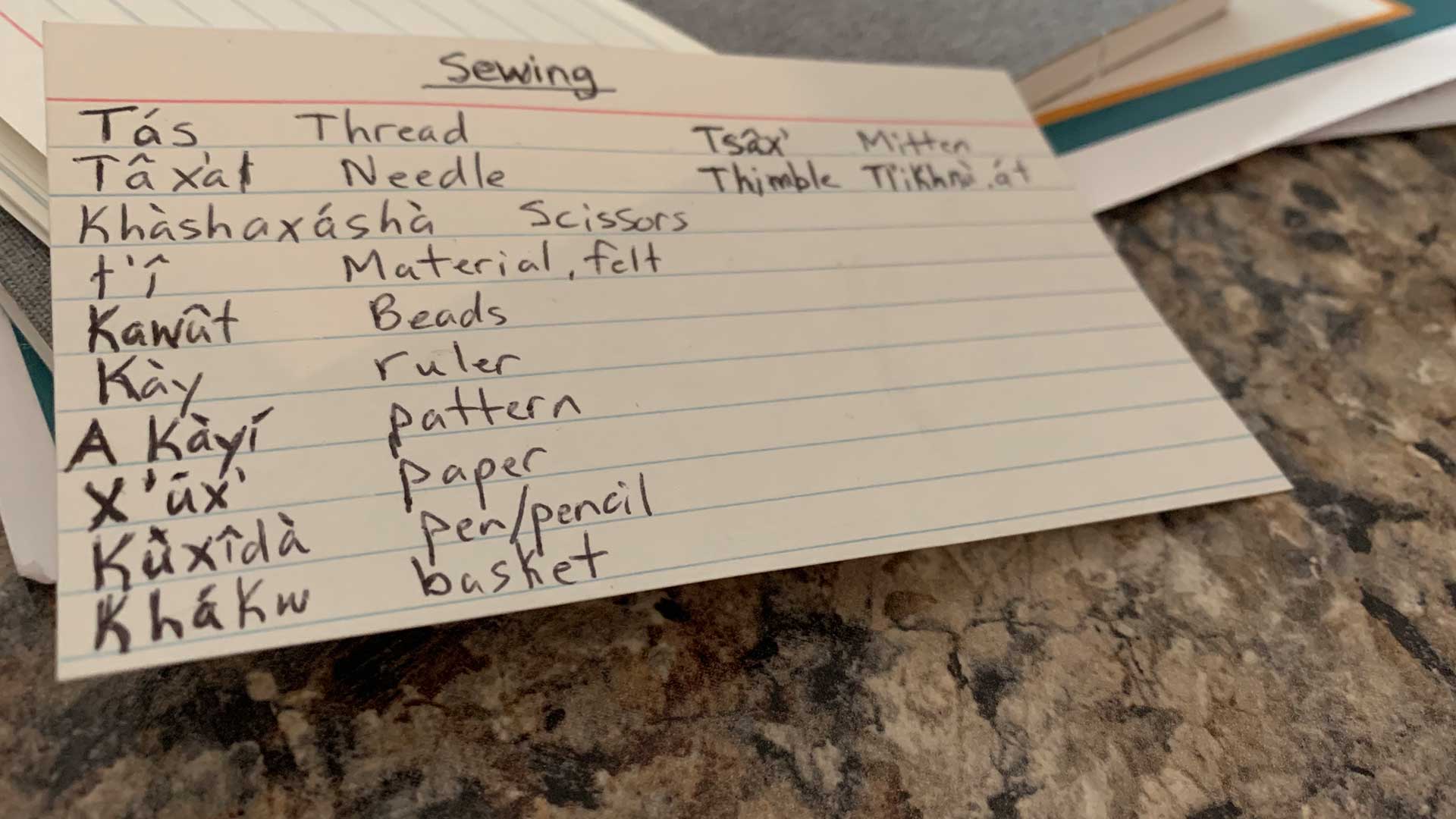

Champagne and Aishihik First Nations (CAFN) invested $1 million in an immersive three-year Southern Tutchone program and pays students to take the course so they can fully focus on their studies.

Mostly only Southern Tutchone is spoken in class, and elders attend classes three days a week to reinforce the language by teaching cultural practices that most students haven’t had the opportunity to learn.

Chief Steve Smith told APTN its cohort of eight students taking the Indigenous languages program have greatly improved their language skills and there’s now a waitlist for next year’s session.

Some graduates of the program will eventually work in the local daycare in what is commonly referred to as a “language nest program,” or early language learning programs, where young children from infancy to five years of age are fully immersed in an Indigenous language.

Tlen said that by teaching children Indigenous languages as early as possible, there is hope for these languages to be carried on.

“Kids are unabashedly copiers and they love learning this stuff, and they soak it up too. I think that’s where the future of Native language is, it’s in the children.”

The YNLC has also made massive strides to preserve the territory’s languages.

A training and research language facility located inside of Yukon University, the centre is administered by the Council of Yukon First Nations with funding provided by the territorial government.

Through the centre, linguists like Tlen have done extensive language documentation and have recorded numerous elders for language preservation.

The centre also offers a wide range of linguistic and educational services to Yukon First Nations and to the general public, as well as offering Zoom language classes in all eight languages to around 200 students.

Never too late to learn

Gus Morberg is one of those students.

While finding the time to study while working full time hasn’t been easy, Morberg said his employer, the Yukon First Nation Education Directorate, supports his decision to learn and lets him leave work early in order to attend classes.

Despite the challenges learning a language later in life can bring, Morberg said it’s worth it.

“Before I lived a healthy Tlingit lifestyle. I fish, hunt, trap and harvest medicines, but there was just something missing in my life, like a void. Once I started learning the language, I realized that was the void and I’m now filling it with learning my language.”

While he’s only been in class a short time, he said he’s now able to pass on a few greetings to his two teenage children – something he never thought he’d be able to do.

“When they come home I’ll say, ‘Waa sa i tuwatee?,’ which means, ‘How are you doing?’

“With a little coaxing they’ll respond. My daughter will say, ‘Xat yak, waa sa i tuwatee?’ which means, ‘I’m good, and you?’ That makes me feel really proud to be a part of that,” he said.

Morberg eventually hopes to start teaching the language to other Tlingit people when he becomes more fluent, and said he’s proof you’re never too old to start learning.

“I’d like to set a good example for the younger people in my nation and show them that anything’s possible. I’ve come a long ways and I’ve overcome barriers to learn the language, and if I can do it, so can you.”