Michael Wrobel – Institute for Investigative Journalism – Alexis Riopel – Le Devoir – Tom Fennario – APTN News

The federal government has acknowledged for at least 13 years that the maintenance of First Nations’ water and wastewater infrastructure is underfunded.

Despite additional investments made in the last two years, the policy changes long promised by Ottawa have been slow to materialize.

Interviews conducted with hundreds of people on the ground—First Nations leaders, community members, water operators, academics and engineers—show the consequences of these policies are severe and put communities at risk.

“I have to beg to get money,” said Mervin Lathlin, a water plant operator in Shoal Lake Cree Nation in Saskatchewan, adding that shoestring budgets leave First Nations little choice but to “juggle funding around” and sometimes delay bill payments.

He said there have been a few times when local suppliers have held up shipments of the chemicals needed for water treatment because the community didn’t settle a bill in a timely manner.

“That’s when I start panicking,” Lathlin said.

On one occasion, he was able to borrow some chemicals from the neighbouring Red Earth Cree Nation to hold him over until he’d finally received his shipment.

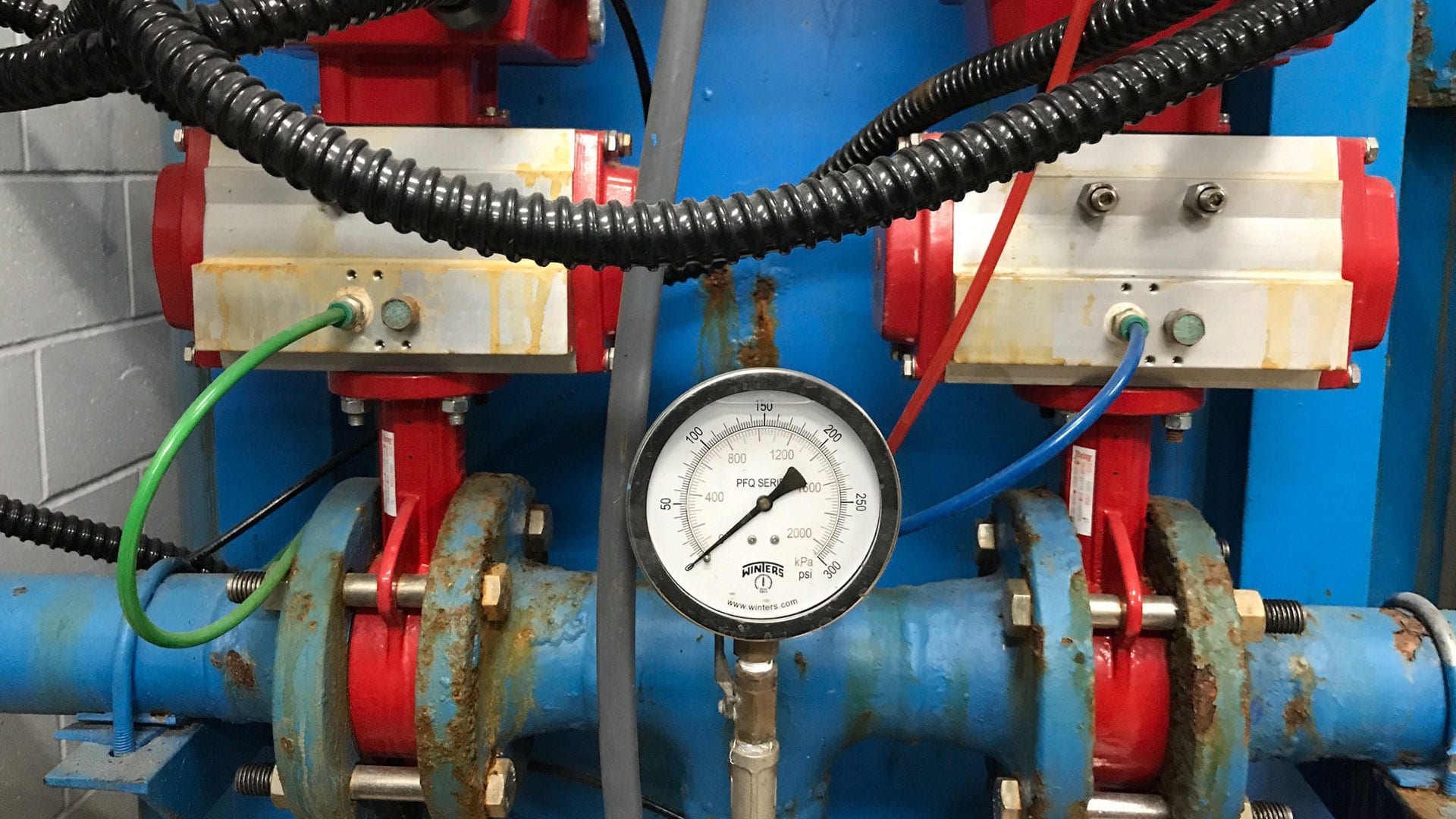

Many infrastructure assets on reserve lands are not reaching their full life expectancy due to a lack of maintenance, poor design and other factors, according to a year-long investigation.

During the 2015 federal election campaign, Justin Trudeau promised a Liberal-led government would end all long-term boil-water advisories in First Nations communities—those lasting longer than a year—by March 2021.

Last December, federal officials recognized they wouldn’t meet that goal.

Since 2015, more than $1.74 billion of targeted funds has been invested to support water and wastewater projects on reserves, but the operations and maintenance (O&M) of these systems has been underfunded for years.

Between 2015 and 2018, federal contributions to the operations and maintenance of on-reserve water and wastewater systems averaged $146 million per year, according to data provided by Indigenous Services Canada (ISC) to the consortium.

But in December 2017, the Parliamentary Budget Officer (PBO) estimated that annual O&M spending needed to be $361 million.

Federal funding therefore amounted to only 40 percent of estimated needs.

The PBO also acknowledged that its estimate is “sensitive to assumptions about population growth and other demographic factors.”

If a higher estimate for population growth had been used, estimated annual O&M needs would instead have been $419 million, according to the PBO’s report.

Ottawa funds the design and construction of water and wastewater systems on First Nations and its policy has been to provide 80 per cent of the funding needed for their operations and maintenance, but First Nation band councils are responsible for the day-to-day management of these infrastructure assets.

Read More:

Indigenous services minister ‘alarmed’ by allegations about construction practices on First Nations

In a 2018 presentation given to representatives of the Assembly of First Nations and obtained by our team, ISC officials projected that one in five of the federally funded water and wastewater infrastructure assets on reserves will not “remain operational for their [full] life-cycles.”

The presentation suggested that O&M plays a role in the premature deterioration of infrastructure, as do factors like “poor design and construction, and [the] age of assets.”

The presentation also said the “inequalities” generated by ISC’s current funding policy have “directly contributed” to the socio-economic gap separating many First Nations from non-Indigenous communities.

ISC was aiming to implement a new O&M funding policy beginning in April 2019, according to the presentation, but that new policy isn’t yet in place.

In administrative jargon, “O&M” refers to all of the day-to-day activities that ensure residents receive safe drinking water, from the salaries of water operators and public works personnel who work in water treatment plants and distribution systems, to the cost of supplies, chemicals used to treat water, electricity, replacement parts and inspections.

The underfunding of O&M “means not being able to pay operators appropriate wages, not being able to hire extra support staff so a lot of operators are overworked, and then just not really being in a position to deal with small problems as they arise,” said Tim Vogel, a doctoral student in engineering at the University of Saskatchewan who researched the obstacles to providing safe drinking water in First Nations.

Current funding levels for O&M don’t allow First Nations to meet the same operating standards for water and wastewater systems as Ontario municipalities, said Tom Sayers, an employee of the Windigo First Nations Council whose job is to provide technical support and training to water operators in five communities 32 in northwestern Ontario.

“You can’t pay enough for wages, you can’t pay your hydro bills, you can’t pay for chemicals,” he said.

Chief Scott McLeod of Nipissing First Nation—who is also the Lake Huron Regional Chief of Anishinabek Nation, an organization that acts as a political advocate for 39 member First Nations across Ontario —said that after an E. coli outbreak in 2000 was linked to contaminated water in the Ontario town of Walkerton, the government took swift action, “dumping a lot of money into proper training [of operators] and management of water and wastewater facilities.

“Well, we’re sitting on a powder keg in a lot of these First Nation communities as a result of [a] lack of proper training, lack of proper resources, to run these [infrastructure assets].

It doesn’t matter if you spend $8 million on a water treatment plant, if you don’t have the people properly trained or pay proper wages to man those facilities,” he said.

As part of the consortium’s collaborative investigation, journalism students conducted phone interviews with water operators and public works directors in First Nations communities from coast to coast.

One in three operators said they faced issues accessing the funding needed to run their water plants and distribution systems. Nearly 23 per cent of interviewees said ISC website, “Contributions to Support the Construction and Maintenance of Community Infrastructure” they don’t have enough O&M funding.

Another per cent expressed other funding-related concerns—for instance, that it can take a long time for funds to be unblocked when emergency repairs are needed.

The underfunding of O&M has led to “an infrastructure deficit that is much larger in First Nations communities than [the one that] exists in non-Indigenous communities,” said Kerry Black, an engineering professor at the University of Calgary whose research focuses on sustainable infrastructure in northern and remote communities.

The amount needed for O&M is now “exponentially higher,” she added, because of the amount of maintenance that wasn’t done over the years for lack of funding.

“Taking care of [those assets] every step along the way is a much more efficient process than neglecting it for years on end,” she said.

Difficult choices

On the Pikogan reserve lands in Quebec’s northwestern Abitibi-Témiscamingue region, Abitibiwinni First Nation’s council has always seen water services as a priority and has chosen to devote the sums needed to ensure their water and sewer systems are properly maintained.

However, this is done at the expense of other needs, said the nation’s chief, Monik Kistabish.

“There’s definitely an impact on housing, because it’s all interrelated,” she said, adding that the community’s roads are also affected.

Martine Bruneau, Abitibiwinni’s director of public works and housing, said repairs in housing owned by the First Nation are often delayed.

Overcrowding makes the budget shortfall worse by increasing wear and tear inside homes, she added.

In remote communities, the costs of repairs are increased by the distance to urban centres.

Repairing a high-voltage control panel, for example, may require the services of a specialized electrician.

In remote First Nations on the northern shore of the Gulf of St. Lawrence, the electrician would have to fly in.

Replacing a single fuse can end up costing between $1,500 and $2,000, according to Marc Lemay, a trainer working for the Mamit Innuat Tribal Council whose job is to help and advise water operators in six First Nations communities in Quebec.

Finding qualified water operators is also a challenge for many communities.

Deon Hassler, a former water operator from Carry the Kettle Nakoda Nation who now trains other operators in Saskatchewan as an employee of the File Hills Qu’Appelle Tribal Council , said many First Nations are having trouble replacing operators as they retire.

“I’ve got about five operators that want to retire and we’re trying to find some new people that are interested in doing [the job]. It’s not easy,” he said. “We had some good experiences in a couple of the communities, but when they see the operator’s salary, again, it’s not very encouraging for them to stick around.”

In recent years, First Nations have also had to deal with the fact that new water treatment technologies are often costlier to operate than older ones.

Joy Cramer, a member of Sagkeeng First Nation with family ties to Sandy Bay First Nation, is the chief executive officer of the Southern Chiefs Organization, which represents 34 First Nations communities in southern Manitoba. She said many of the new water treatment plants being built in First Nations use membrane filtration systems, which are very effective at removing bacteria, microorganisms, particles and organic matter, but have high operating costs.

“If a membrane breaks down, we know that the cost to replace that membrane is more than the annual maintenance [budget] for that community, so then they go without because they don’t have the money to replace the membrane,” she said.

“Why are we buying systems where the cost to replace parts is more expensive […] than the annual maintenance budgets?”

Systems too costly to operate

In some communities, the high costs of maintaining existing systems are a motivating factor for seeking funding from the federal government for their replacement.

In 1999, Kebaowek First Nation wanted to replace its then-deficient wastewater treatment system.

Chief Lance Haymond said an experimental biofiltration technology was proposed by a federal civil servant and ultimately implemented.

The technology had, until then, mostly been used on pig farms.

But Terry Perrier, the director of public works and community infrastructure in the Anishnabeg Algonquin community of western Quebec, said the research centre that created the system wanted to get it approved for use in municipalities and First Nations.

The biofiltration technology treats wastewater by making it pass through a bed of wood chips, bark, peat and microorganisms that trap and break down pollutants.

“We became a pilot project,” Perrier said.

He said it soon became apparent the facility would cost more to run than estimated.

“The initial cost was low, but it turned out the O&M costs were getting ridiculous because the [filtration material] that would treat the sewage was lasting about a third of the time they had told us [it would],” Perrier said.

“They told us, ‘in ten years, you’ll probably have to replace this,’ but we were replacing it about every three years.”

Perrier said the filtration material was last replaced at a cost of approximately $250,000.

“[It required] three quarters of a million dollars every ten years just to keep that running. That’s crazy. So we knew it wasn’t a good system to have,” he said.

Less than two decades after implementing the biofiltration system, “we had to ditch that technology because it didn’t meet [our] needs,” said Haymond.

In 2017, Kebaowek built a new wastewater treatment plant with $9.8 million in federal funding.

The new system uses “an old tried-and-true method of treating sewage,” Perrier said, and was designed with the community’s future growth in mind.

He added it will be cheaper and simpler to run than the old plant.

Still, the underfunding of O&M continues to have impacts on the community.

“Based on the money I’m given to run [the water treatment plant] and the money I spend to run it, I’m in a deficit,” said Perrier.

New federal investments

The federal government is increasing O&M funding for water and wastewater systems in First Nations communities.

The 2019 federal budget included $605.6 million in new funding for the operations and maintenance of on-reserve water and wastewater systems.

That’ll be dispensed over four years, beginning in the 2020-21 fiscal year.

Last December, ISC Minister Marc Miller announced more than $1.5 billion in additional investments into on-reserve water infrastructure, including another $616.3 million over six years and $114.1 million per year thereafter to support O&M.

“These additional funds, in part, are expected to assist First Nations in their ability to retain qualified water operators,” ISC said in a statement emailed to the consortium.

ISC declined a request from the consortium to provide a detailed breakdown for how the new funding would be rolled out, year by year.

The department also didn’t specify whether these new investments are in addition to core funding—and if so, how much core funding there will be moving forward.

In earlier responses to the consortium’s questions, ISC spokespeople said “permanent ministerial funding” for water- and wastewater-related O&M totalled $109 million during the 2018-19 fiscal year.

Without more detailed information, it’s unclear whether total annual funding will meet the O&M needs estimated by the Parliamentary Budget Officer in 2017 to be $361 million.

In an interview with the consortium in December 2020, Miller explained that these investments are part of the government’s strategy to “ensure access to clean and safe drinking water for generations to come for every community.”

“There have been immense financial commitments made,” he said.

“We have a lot more work to be done, but our […] long-term commitments in and around O&M are part and parcel of that discussion.”

Experts interviewed by the consortium are waiting to see the results of the new investments before saying whether they’ll be enough to fully tackle O&M needs.

In several communities, the maintenance backlog is significant.

Moreover, ISC’s O&M policy and funding formula—which the government had also promised to update—have not yet been changed.

“The work will have to be done over several years, through training, [increasing] salaries.

For the moment, I think it’s too early to say,” said Jean-François Savard, a professor at a Quebec public policy school, the École nationale d’administration publique (ÉNAP), whose research interests include the relationship between the federal government and Indigenous peoples.

The federal government made these new investments almost 10 years after the 2011 publication of the National Assessment of First Nations Water and Wastewater Systems, a report prepared for ISC by engineering firm Neegan Burnside.

The report warned that O&M was underfunded.

An internal audit of the department’s infrastructure program had also acknowledged problems with O&M budgets the year prior, in February 2010. “O&M funding shortages are felt most acutely in rural and remote First Nation communities,” the audit read.

The department’s O&M policy has not changed significantly since 1998.

To determine how much funding for O&M will be provided to each First Nation, ISC uses a formula created in the 1980s.

The formula takes baseline costs for inspections, materials and other aspects of O&M and adjusts them for regional price variations and other factors, like a community’s remoteness.

First Nations leaders, several engineers, university researchers and the federal government itself have all acknowledged that the policy and formula are outdated and inadequate.

“It’s not really based on what the real cost is to sustain that asset. It’s based on this funky, 30-year-old model that was developed when infrastructure was lightyears simpler than it is now,” said Craig Baker, the general manager of First Nations Engineering Services Ltd., a Indigenous-owned company that has designed water treatment plants for many First Nations.

The funding formula notably takes into account the square footage of water treatment plants, providing more funding to larger facilities, Baker said. Because of this practice, First Nations end up receiving less if they have facilities with newer technologies that take up less space—even though these are often more complex and costly to operate.

M’Chigeeng First Nation is among the First Nations affected.

The Ojibwe-speaking community on Lake Huron’s Manitoulin Island had two options for its new water treatment plant: install a small plant using new technology on the lot meant for it, or relocate the plant to a larger site and rely instead on an older technology like slow sand filtration.

Although the first option is more expensive to maintain, Baker said, the second option is what the formula rewards.

ISC’s formula also assumes that First Nations will cover 20 per cent of water-related O&M costs themselves, leaving the federal government to foot the other 80 per cent.

But many First Nations have limited ability to generate revenue through property taxes, water fees or band-owned businesses, making it difficult to cover their portion.

First Nations leaders have long criticized that cost-splitting.

The Chiefs of Ontario raised concerns about it in a 2001 report they submitted to the Walkerton Inquiry that followed the E. coli outbreak linked to Walkerton’s water supply.

“Many First Nations are having considerable difficulty in charging and collecting […] user fees owing to high costs of living and high levels of unemployment in their communities. This leads to a built-in [funding] shortfall,” the report noted.

In July 2017, then-Minister of Indigenous and Northern Affairs Carolyn Bennett said the government was working with the Assembly of First Nations (AFN) to revise its method of calculating O&M funding.

“This policy is outdated, and simply does not reflect the realities First Nations communities face,” she said.

Slides from a 2018 presentation that were not intended to be made public, but which the consortium managed to obtain, confirm that ISC is working to reform its O&M policy and funding model.

Indigenous Services Minister Marc Miller said last year the federal government is moving towards fully covering O&M costs related to on-reserve water and wastewater infrastructure.

In a statement to the consortium, ISC said it will fully cover all O&M costs this year. “O&M funding for 2020-21 will go out,” wrote ISC spokesperson Leslie Michelson.

“The new O&M funding announced by Miller on Dec. 2, 2020, will enable an increase to 100 per cent of formula-based funding for operations and maintenance.”

A new policy in the works

In the fall of 2019, the AFN passed a resolution at its Special Chiefs Assembly to push the government to abandon its O&M formula and instead adopt so-called “asset management planning.”

This approach requires that the operations, maintenance and upgrading of infrastructure be strategically planned throughout an infrastructure asset’s entire life cycle.

If this approach were adopted, each First Nation’s funding would be based on the costs they actually incur over an asset’s lifespan and what’s needed to make infrastructure last as long as possible, not a one-size-fits-all formula.

The asset management approach is increasingly being adopted by municipalities.

As part of pilot projects organized by the AFN in a dozen First Nations across Canada, independent consultants developed asset management plans for each participating nation with the goal of better understanding the impacts of such a change in funding model.

The pilot projects revealed significant maintenance and upgrade backlogs, according to a presentation given by engineer Craig Baker to the AFN in the spring of 2020.

The reports prepared as part of these projects covered not only O&M related to water and wastewater systems, but roads, community buildings and other assets.

They confirmed that funding shortfalls for O&M are a “chronic” problem for all types of First Nation infrastructure.

In Alberta, ISC funds 21 per cent of the O&M required for all infrastructure assets belonging to the Louis Bull Tribe, according to a report commissioned by the AFN.

In Ontario, three First Nations—Moose Cree, Kasabonika Lake and Curve Lake—received 28 percent, 60 per cent and 22 per cent of the funds required for O&M respectively.

In Quebec, Kebaowek received 33 per cent of the funding deemed to be needed by consultant Marie-Élaine Desbiens.

An asset management specialist, Desbiens said the adoption of a funding model based on asset management planning will not only be useful for First Nations, but also for the government.

“With an understanding of long-term needs, decisions on the allocation of funding become more structured, more informed,” she said.

In an interview, Miller confirmed that his department is co-developing a new funding formula with the AFN.

Asset management is one of the approaches being considered.

However, he did not offer a timeline for when these reforms will come into effect.

“I’d like to see it change as soon as possible,” he said.

With files from Erica Endemann (Carleton University), Danna Henderson (First Nations University of Canada), Theresa Kliem (University of Regina), Lila Maître (Université du Québec à Montréal), Tom Fennario and Brittany Hobson (APTN News), Krista Hessey (Global News), Annie Burns-Pieper, Patti Sonntag, Emma Wilkie, Colleen Kimmett and Declan Keogh (Institute for Investigative Journalism)

Concordia University:

Laurence Brisson Dubreuil, Luca Caruso-Moro and Kaaria Quash, with the help of Charlotte Glorieux, Olivia Johnson, Tristan McKenna and Stephanie Ricci Instructor: Patti Sonntag Université du Québec à Montréal: Philippe Julien-Bougie, Geneviève Larochelle-Guy, Lila Maître, Bruno Marcotte, Étienne Robidoux Instructors: Patti Sonntag et Jean-Hugues Roy Le Devoir: Project lead: Anabelle Nicoud This article is a compilation of reporting by students and journalists at colleges, universities and media companies nationwide, including: Carleton University, Concordia University, First Nations University of Canada, Humber College, University of Regina, MacEwan University, Mount Royal University, Université de Québec à Montréal (UQAM), University of British Columbia, University of King’s College.

See the full list of “Broken Promises” series credits and more information about the consortium on the Clean Water, Broken Promises website. Produced by the Institute for Investigative Journalism, Concordia University For tips on this story, please contact the reporters at: iij.tips(at)protonmail.com