Warning: This story contains descriptions of sexual violence and language that some may find disturbing.

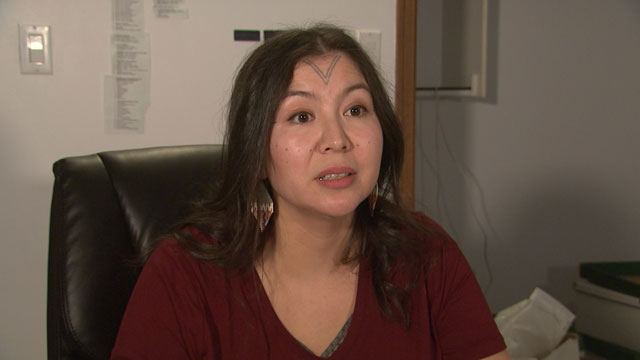

Every community has a whisper network; women who quietly warn other women about men who are potentially a threat. When Nunavut actor Johnny Issaluk received an Order of Canada and was nominated for an Indspire award, those whispers got so loud that Inuit filmmaker Alethea Arnaquq-Baril felt she had to shout.

“We talk, especially as women. We talk about who is safe to be around, who’s not. There are whisper networks,” explained Arnaquq-Baril.

Arnaquq-Baril had cast Issaluk in a short film about Inuit games which aired at the 2010 Vancouver Olympics.

A few years later at a party in Iqaluit, she said he crossed the line.

“He touched my bum, and not just like a brush that could have been an accidental bump. He fondled me, it was 100 per cent a sexual touch. I was shocked. I had no idea it was coming. It just came out of nowhere. Completely uninvited. No flirtation at all, not that it matters,” explained Arnaquq-Baril.

“It stunned me, I immediately gave him an earful. I yelled at him, I didn’t care who was listening, I might have made a point of making sure other people heard. He was apologizing profusely, on the spot. I was willing to forgive him, especially because he did apologize fully and very quickly.”

She said soon after, some of the other women at the party came up to her with their own stories about Issaluk’s behavior.

“An unexpected side effect of me scolding him so loudly was that the women there came to me the same evening with their own stories, of similar things that he had done to them, or to their friends or their cousins. From then on I knew he was described as pretty creepy,” she said.

Issaluk’s career began to skyrocket, becoming one of the best known Inuit actors in Canada.

He appeared on the television series Murdoch Mysteries in 2016, and the Iqaluit filmed feature film Two Lovers and A Bear in the same year.

In 2017 he had a role in the film adaptation of Richard Wagamese’s novel Indian Horse. The next year, a significant role in the AMC horror series The Terror.

Arnaquq-Baril’s career was on the same upward path.

Her 2016 documentary Angry Inuk won two awards at the Hot Docs Canadian International Documentary Festival. Two more awards followed from the Montreal International Documentary Festival, and she finished the year with the People’s Choice award at the Toronto International Film Festival Top 10 Festival, which features Canadian Films.

She said the stories about Issaluk kept coming over the years, and “they got worse and worse. I started to feel responsible in some way, because I had cast him in my short film that was seen far and wide. It very probably helped get him more work in the film industry. His public profile grew and grew.”

With that public profile, Arnaquq-Baril began to fear that Issaluk had gained access to many more women.

“He just kept being put in situations with other women, young women. I’ve come to accept that it’s not my fault, and I don’t feel any shame about what he did to me. I didn’t know at the time,” explained Arnaquq-Baril.

Watch Kent’s story on Johnny Issaluk

Arnaquq-Baril said she decided to act as Issaluk’s star climbed to unforeseen heights.

In December 2019, he received the Order of Canada and was slated to receive an Indspire award this year.

She described her experience with Issaluk in a social media post shared on Twitter and Facebook. The Tweet that began her declaration has been retweeted over 400 times and has over 1,600 likes.

She said she doesn’t regret it.

“In some ways, I wish I had of come out sooner with this story, and saved some other people some heartache or trauma or feelings of guilt,” she said.

Her post begins, “This is an incredibly difficult thing to write and put out there publically. But I am fucking DONE protecting violent men.”

She told the story of her own experience with Issaluk, and said that many other women have reached out to her.

“Over the years, I’ve heard many stories. Stories similar to mine, and also much, much worse. Many of them were 3rd/4th hand rumours. But several of them I heard directly from the women who experienced them. They told me they suffered violent physical and sexual assaults from him,” she wrote on her social media pages.

(Johnny Issaluk from the Indspire Awards website)

It ends urging people who were abused by Issaluk to write the Governor General and Indspire, and ask them to take away Issaluk’s honours.

Indspire did just that.

The day after Arnaquq-Baril’s post, Indspire put out a statement.

“Indspire learned yesterday afternoon of the serious allegations concerning Johnny Issaluk. It moved quickly to suspend his 2020 Indspire award. The original nomination will be reviewed by the Indspire jury.”

APTN News contacted the Governor General’s office to see if they were going to review Issaluk’s award.

In a written statement, a spokesperson stated, “The Office of the Secretary to the Governor-General does not comment on allegations made against recipients of Canadian honours.”

Natan Obed, president of Inuit Tapariit Kanatami (ITK), the national Inuit organization did comment on allegations made against the recipients of Canadian honours.

On stage at the Arctic Inspiration Prize awards in Ottawa – just hours after Arnaquq-Baril’s post – Obed addressed the allegations against Issaluk.

“Alethea Arnaquq-Baril made a social media post tonight about sexual abuse. I want to say that I stand by Alethea. I believe her. And I support her,” Obed told the audience.

“We need to stand with those people who need our love and our support in times that are very difficult.”

Iqaluit MLA Adam Lightstone was quick to follow, posting on social media.

“I am grateful that we have such brave women in our community, who have the courage to speak out. There are many deep rooted issues in Nunavut which are often swept under the rug,” he wrote.

“It is important to break the silence in order for our communities to talk more openly about sexual assault, domestic violence and child abuse before we can truly address the situation.”

“I was floored,” said Arnaquq-Baril about the support of those two Inuit men.

“To hear Natan and Adam publically supporting my statement and saying they believe me, I didn’t expect it, because that’s not usually what our politicians have done. I’m grateful that they expressed their support, we need men in leadership positions to be sharing that responsibility. To be condemning abuse, condemning that kind of behavior, to be making it easier for victims to speak out.”

APTN asked Arnaquq-Baril why she didn’t go to the police with the information she was receiving about Issaluk.

“I know in one instance there has been contact with police at times. I would never push someone to go to the cops, if they weren’t ready to. What I’ve been telling everyone who reaches out to me is ‘I hope what I’ve done and said doesn’t make you feel pressured to do the same,’” explained Arnaquq-Baril.

Being wary of police is a reality for Nunavut’s women.

A recent report released by the Pauktuutit Inuit Women of Canada said that many Inuit women in Nunavut are reluctant to call the police because of previous bad experiences.

Last week, an Iqaluit Justice of the Peace refused to sentence a woman for violating her bail conditions, because police discovered the violation as a result of her calling them for help.

In his written decision, Justice of the Peace Joey Flowers wrote, “The big picture is simple—a woman is calling for help against domestic violence. Why charge her for violating her bail conditions by drinking?”

Aside from acting, Issaluk has carved out a niche as an Inuit cultural advisor.

From November 23 to 26 2019, he presented on Inuit culture to a group of 20 women in Tromso, Norway. The women were preparing for a cruise called the Sedna Epic Expedition, to snorkel with orcas.

Following Arnaquq-Baril’s statement, Susan Eaton of the Sedna Epic Expedition put out a statement of her own.

“Subsequent to our return from Norway, Sedna’s leadership team became aware that Johnny had acted inappropriately in Tromso, making unwanted advances towards several of the women (ages 21 to 78 years) which made them feel uncomfortable,” Eaton wrote. “Sedna’s women’s leadership team acted swiftly and decisively, investigating the women’s allegations against Johnny. Finding the allegations credible, we requested (and received) Johnny’s resignation, effective December 9, 2019.”

Issaluk is also an “Explorer in Residence” for the Royal Canadian Geographic Society. He spoke at an event for them in Ottawa the day before Arnaquq-Baril posted her allegations. He has also travelled with them as presenter on their cruises, including a recent one to Antarctica.

APTN attempted to contact the RCGS about the allegations against Issaluk. They did not answer our queries prior to the publication of this story, and his biography has since been removed from their website.

Over the course of days, APTN tried a number of times, in several ways, to reach Issaluk but were unsuccessful.

Late Friday afternoon, Issaluk released a short statement to the Iqaluit media.

“There are no words to express my grief and regret for the pain I have caused. To those I have harmed by my actions: I am truly, truly sorry. It was never my intention to hurt anybody, but I know I did. By not healing from my own trauma, I have hurt others. We must stop this cycle in our community, And I know it starts with me taking responsibility for my actions,” he wrote.

“I am also seeking treatment for my alcoholism, which is no excuse, but has made this behavior worse and caused more pain to those I love. I want to thank my friends and family for their support and I deeply regret the shame that is now shared with them. I hope one day I can earn your forgiveness.”

Issaluk has good reason to believe he can earn the forgiveness of the community, because so many have done it before.

In Nunavut, it is common for a prominent man to admit to wrong doing, and being able to pick their life up right where it left off.

(Hunter Tootoo in 2017 as an Independent MP at a news conference in Ottawa. Photo: APTN)

In 2015, Hunter Tootoo was elected as the Liberal MP for Nunavut and was named minister of Fisheries and Oceans.

By May 2016, he was out of the Liberal cabinet and in addictions treatment.

Tootoo told the Globe and Mail that he had been in a “consensual but inappropriate relationship” with a young woman staffer.

The Globe and Mail later reported that Tootoo had broken off the relationship with the staffer in favour of a relationship with her mother.

The staffer then physically damaged his parliamentary office, which led to his resignation from the Liberals. Upon returning from treatment, Tootoo was able to quietly finish out his term as an independent MP and didn’t offer to run again.

In 2007, then Nunavut Premier Paul Okalik was at a reception at a Trade Show in Goose Bay, Labrador. Then Iqaluit Mayor Elisapee Sheutiapik over heard him remark “who let that fucking bitch in here” when Nunavut Association of Municipalities CEO Lynda Gunn entered the room.

The Nunavut Legislative Assembly passed an official censure of the premier, calling for him to “seek counselling and guidance to assist him.” He was able to continue on as premier and later as a federal Liberal candidate.

James Arvaluk resigned as MLA twice following attacks on women, only to be re-elected each time. He resigned the NWT Legislative Assembly in 1995 following two sexual assault convictions. He was later elected to the Nunavut Legislative Assembly. He resigned again in 2003, after he was convicted of assault for an attack on a woman so vicious that it left a 14 inch cut on her face and permanent nerve damage.

He served nine months jail time for that assault and was re-elected a third time in 2006.

In March 2000, Nunavut MLA Levi Barnabus was convicted of sexual assault for attempting to have sex with an unconscious woman on a couch at a party. He was chased from the home in his underwear by the woman’s husband, who was carrying a baseball bat. He resigned, and was re-elected to the assembly in 2004.

Arnaquq-Baril has reason to believe that this cycle of misogynist action, followed by contrition and a quick return to the status quo, is over for high profile men in Nunavut.

Her post has helped others come forward, and has spawned its own slogan, Uvangalu. Uvangalu is Inuktitut for “Me too.”

Read More:

Actor Duane Howard admits to sex with teenager – she was it was violent, he says there was consent

Accusing Googoo: The chief, the charges, the next chapter

In Nunavut, there are many people who can say,”Uvangalu.” According to Statistics Canada, Nunavut’s rate of sexual assault reported to police is seven times the national average. Sexual assault against children is 14 times higher than the Canadian average.

”I’ve heard women saying ‘uvangalu’ to each other my whole life. To see it put in a hashtag, it was recognizing something that’s a thing that happens all the time. Its taking secret, whispered, private conversations, and making them public and important and validated, so, I loved seeing that hashtag and I hope it continues to be used,” said Arnaquq-Baril.

“I was expecting at least some blowback, I was expecting a lot of blowback actually. Because that has been the experience of a lot of women who speak up against popular or powerful men. I’m grateful, so far it has been 100 per cent positive.”

She hasn’t heard yet from the man at the center of the allegations, Johnny Issaluk.

“I don’t care to. I blocked him on Facebook, I doubt he would have the nerve to reach out to me anyway,” explains Arnaquq-Baril. “Really, this isn’t about him. Doing this wasn’t about shaming him, it was about letting his other victims hear the words that the shame is his and not theirs. We have to stop holding other people’s shame for them.”

As for the wider implications of Nunavut’s sexual assault epidemic becoming more and more public, Arnaquq-Baril has high hopes. “I hope this is the new normal. I think saying these things out loud lets other predators know you’re not an easy target. They can’t count on getting a pass from now on. I love knowing that there are predators all over shaking in their boots right now, across the territory.”

For Nunavummiut struggling with this story or other mental health challenges, the following resources are available.

Nunavut Kamatsiaqtut Help Line — 1-800-265-3333

Kids Help Phone — 1-800-668-6868 or live chat counselling online