A class in session at the Kanatamat Tshitipenitamunu School in Matimekush in eastern Quebec. Photo: APTN.

Michael Wrobel – Institute for Investigative Journalism, Concordia University – Alexis Riopel – Le Devoir

First Nations children are consuming water with unsafe lead levels in on-reserve daycares and schools across Quebec, according to a presentation by Indigenous Services Canada (ISC) staff obtained by a consortium of news outlets and universities that includes APTN News.

While the federal government knows which taps and fountains have lead levels exceeding Health Canada’s guidelines, it has not made its dataset public or notified parents of affected children directly, leaving management of the issue up to individual First Nations.

In many communities where concentrations exceeding the norm have been found, federal officials suggested letting the water run a few minutes at affected taps every morning or, in some cases, at the start of every week. Experts said this is not a reliable long-term solution.

Michèle Prévost, a professor at the Polytechnique Montréal engineering school and a leading expert internationally on the issue of lead in drinking water, said exceedances of Health Canada’s guidelines in daycares are “always concerning because very young kids are most at risk from the adverse effects of lead on their development.”

“It’s crucial to issue a notice that asks [daycare] staff not to prepare infant formula” with water from faucets that aren’t compliant with the guidelines, she said.

Levels of exposure thought to be safe 30 years ago have now been linked to attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), lower IQs and academic performance, behavioural problems and delayed puberty in scientific studies.

In 2017, ISC organized a large sampling campaign of schools and daycares in 28 First Nations communities across the province, focusing on taps and water fountains used for drinking and food prep. Samples were collected at random times during the day, without letting the water run beforehand.

A presentation prepared by ISC employees on the resulting data and obtained by a consortium including APTN News, Le Devoir, the Université du Québec à Montréal (UQAM) led by Concordia University’s Institute for Investigative Journalism (IIJ) reveals that out of the 901 faucets and water fountains that were tested, 69 had levels above the limit of 10 micrograms per litre (ug/L) that was Health Canada’s guideline at the time.

At the same time that ISC was organizing its sampling campaign, Health Canada was reviewing its guideline for lead, with plans to lower the maximum acceptable concentration to five ug/L—a step eventually taken in March 2019. ISC’s presentation notes that 147 taps (16.3 per cent) had lead levels above the new limit. The highest value found through testing was 151 ug/L, over 30 times the new norm.

The presentation only provides overall statistics, not the results from individual schools and daycares. In response to questions from reporters, ISC provided the consortium with a list of the communities that took part in the sampling campaign, but declined to share where exceedances were found.

“ISC collects and uses data with permission from Chief and Council in each community. However, the information belongs to the individual communities, not [ISC’s First Nations and Inuit Health Branch]. Only communities can release their specific data as they deem appropriate according to their own protocols,” said ISC spokesperson Leslie Michelson.

She added that measures have been taken to address lead exceedances and that follow-up testing has been carried out since 2017.

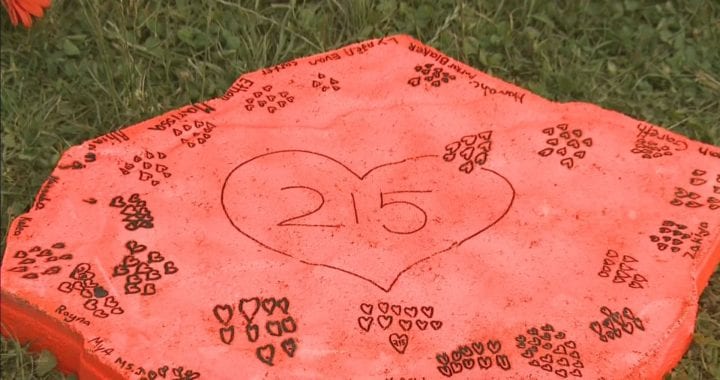

Matimekush—an Innu Nation in northeastern Quebec, near the town of Schefferville and the provincial border with Labrador—agreed to provide the consortium with its results. Among the 27 taps tested at the community’s Kanatamat Tshitipenitamunu School in 2017, four showed a lead concentration exceeding five ug/L. At one faucet, the concentration reached 65 µg/L.

Jean-Baptiste Laurent, director of technical services in Matimekush, said he was informed of the exceedances in 2018 through a letter sent a few months after the tests had been performed. He said he was advised by the First Nations and Inuit Health Branch to let the water run for 10 minutes each morning.

Laurent relayed these instructions to the school. Three years later, this practice is still in place. According to Laurent, the federal government has not yet conducted any follow-up tests with the community’s help.

The director said he no longer remembers whether the First Nation or school administrators had informed parents in 2018, but he said he doubts they would have been. “I found that it wasn’t alarming,” he said. “If all the results had been exceedances, something would have been done. But since there weren’t many, I think it would have just scared people and they would have stopped drinking the water.”

Two of Mélodie Fortin’s kids attended Matimekush’s school. The Innu mother said she was never made aware of the risks associated with lead-contaminated water. “I believe that this is something important to consider for the health of our children,” she said.

Fortin’s four-year-old son will soon be starting kindergarten at the Kanatamat Tshitipenitamunu School. She said she’s worried her son may end up drinking from one of the taps that don’t comply with public health guidelines. “A little child going to the fountain, that can always happen. You can’t watch them all the time,” she said.

A neurotoxic metal, lead can affect children’s cognitive development even in small quantities. The World Health Organization says there is no safe level of exposure. Health Canada recommends that community water systems keep lead levels “as low as reasonably achievable” in drinking water, while the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the U.S. say “all sources of lead exposure for children should be controlled or eliminated.”

In buildings like schools, lead typically leaches out of older plumbing fixtures and solder—the filler used to join pieces of copper pipe. The longer water is stagnant in pipes, the more time lead has to dissolve into the water.

The consortium attempted to contact 25 First Nations communities where testing took place in 2017. Of those who responded, several said they were unsure whether such testing had been carried out. Others were not able to immediately track down the results.

Donna Metallic, the health director in Listuguj, confirmed that the Alaqsite’w Gitpu School and daycare in the community were tested as part of the 2017 sampling campaign. Follow-up testing was done in both 2018 and 2019.

At the daycare, out of 11 faucets that were tested in 2017, five had lead levels above five ug/L. Lead levels were compliant with guidelines at taps in the daycare’s nursery and toddler room. But there were non-compliant taps in a playroom, a staff room and a kitchen in the building’s basement, as well as in a bathroom on the main floor.

New rounds of testing in 2018 and 2019 confirmed the taps in the basement were problem spots, with lead concentrations continuing to be above recommended levels. Over the three years, results at those non-compliant faucets ranged from 5.5 ug/L, just slightly above the guideline, to 19.6 ug/L, nearly four times the recommended limit.

Roger Metallic, who monitors water quality in Listuguj, said in an email that he helped an environmental public health officer from ISC with the collection of follow-up samples. “On one occasion, I was present when the daycare centre’s staff […] were advised to run the taps in the basement to prevent stagnation of the water and the leaching of lead into the water,” he said, adding that when he went back for regular water testing a couple of months later, staff members told him they were doing so.

All 20 faucets tested in 2017 at Alaqsite’w Gitpu School were compliant with Health Canada’s guideline, but new rounds of sampling in 2018 and 2019 found lead levels above the limit at a fountain in one classroom, where the test results in those years were 10.9 and 6.2 ug/L respectively.

All taps and fountains at Timiskaming First Nation’s Kiwetin School were tested in 2017, according to Corey Stanger, the Algonquin community’s director of public works. He said a faucet in a classroom and a water fountain in a hallway were found to have lead levels above Health Canada’s guideline.

In an email, Stanger said ISC’s recommendation for the community was to flush the two taps for five minutes each morning to remove water that had been stagnant in the pipes overnight, or to post signs at the non-compliant faucets that they are only to be used for handwashing and cleaning, not drinking or filling water bottles. “My understanding is that the faucets were flushed regularly,” he said.

Stanger said another round of testing in September 2019 showed those faucets “were satisfactory by that point.” No testing has been carried out this year due to COVID-19 restrictions, he added.

Kebaowek First Nation, also in the Abitibi-Témiscamingue region, doesn’t have its own school—children instead attend off-reserve schools—but the community does have a daycare.

Terry Perrier, Kebaowek’s director of public works and community infrastructure, said water samples from some of the community’s public buildings, including the daycare, have been tested for metals such as copper and lead. The lead results came back fine, he said, but copper levels were found to be elevated at some taps after water had been stagnant in pipes for an extended period.

Unlike lead, which has no useful purpose in the body, copper is an essential element that humans must consume in their diet. Consumption of significant levels of copper through water can nevertheless lead to nausea and diarrhea. The levels of copper found in water are usually more of an aesthetic concern than a health one, because copper can affect water’s taste, as well as stain laundry and plumbing fixtures.

“[In] certain spots in the buildings, the taps don’t get used enough,” Perrier said. “The fix is, on a daily basis, just, you know, somebody goes into that room and runs the tap.”

An inadequate solution

In an email, an ISC spokesperson said that wherever lead concentrations exceeded five ug/L during testing in 2017, taps were “either labelled as ‘only for hand washing or cleaning’ or closed, at the discretion of community authorities, until further investigation and/or corrective actions could be completed and confirmed through sampling to have been effective.”

Running the water every Monday, after water had been stagnant in schools’ pipes all weekend, “was, in several cases, sufficient to reduce the lead concentration to an acceptable level,” wrote the spokesperson in response to questions from the consortium. She said that if the five-minute “flush” wasn’t sufficient, federal officials were available to help communities implement other fixes, such as installing filters on non-compliant faucets, providing bottled water or replacing plumbing.

But in a scientific article published in 2018 about lead in schools, Prévost and her team of researchers at Polytechnique Montréal criticized the solution of letting the water run in the morning once a week or once a day. “Extended flushing of taps in the morning is ineffective for lowering lead […] concentrations throughout the day,” the researchers wrote.

Their study, which tested 130 taps and fountains, found that after just 30 minutes of stagnation, lead concentrations rose to at least 45 per cent of what they were in the morning, after water had been stagnant in the pipes overnight.

“Flushing […] isn’t sufficient to protect kids,” Prévost said in an interview. “Once a week, that’s worse than once a day, because the concentration of lead goes back up after a half an hour, and certainly after a few hours of non-use, which is a perfectly plausible scenario during a school day, in between recesses or uses.”

Only flushing for a minute or two before each use can work, but it’s something people will often forget to do, she said.

In contrast, replacing older plumbing components—sometimes just the faucet itself—is often an effective solution. Lead was used as a piping material in Canada until 1975 and in solder until 1986. Faucets with brass components were allowed to be between two and eight percent lead until 2014, when further restrictions were introduced on lead content in plumbing. Today, new faucets can only be up to 0.25 percent lead.

The use of certified filters, which can be installed on faucets or under sinks, has also proven to be effective, Prévost said.

In Matimekush, Laurent is now considering requesting that federal officials take new samples to see if there’s room for improvement. “It’s certainly making the light bulb go on,” he said after looking back at the 2017 results.

Tests proceeding in provincial schools

Problems with lead in water are not unique to schools and daycares in First Nations communities. According to Quebec’s public health research institute, the Institut national de santé publique du Québec (INSPQ), 3.3 per cent of the samples collected in 436 provincial schools between 2013 and 2016 exceeded Health Canada’s guideline of five ug/L.

Those samples were taken, however, after letting the water run for five minutes, a sampling method widely criticized by experts for not mimicking typical usage and significantly underestimating people’s actual exposure levels. The INSPQ acknowledges this, noting in a report that the testing method used at the time by the province underestimates lead levels compared to the protocol used by the federal government on reserve lands.

The federal government’s testing method, which involves randomly sampling taps during daytime hours without letting the water run beforehand, isn’t perfect either, Prévost said, noting that it can fail to detect non-compliant faucets and fountains if samples happen to be taken shortly after they were last used.

Premier François Legault’s government changed the province’s testing method after a 2019 investigation by the Institute of Investigative Journalism, Le Devoir and Global News showed the extent to which its previous method was underestimating lead concentrations, and after additional reporting by La Presse showed high lead levels in some Montreal-area schools’ water.

The province lowered its lead limit from 10 ug/L to five ug/L, bringing it in line with Health Canada’s new guidelines, and also required that all provincial schools measure the concentration of lead at all fountains and faucets used for drinking or food prep by March 1. School administrators will have to advise parents of any concentrations exceeding the regulatory norm, as well as put corrective measures in place based on the results of testing.

According to Prévost, the provincial education ministry has sent a clear message in its directives to schools that it expects filters to be installed or taps to be either replaced or permanently shut off wherever lead concentrations are found to exceed five µg/L.

All establishments offering childcare services in Quebec, including those in First Nations communities, were also asked by the province to participate in the testing campaign and “the results were gradually received by Quebec’s Family Ministry,” said a spokesperson for the ministry in an email sent last November. As was the case with the federal government, the spokesperson said results from the water testing belong to each daycare and that consequently, the ministry cannot share detailed lists revealing results.

Prévost said it’s important that local public health personnel in each First Nation explain the dangers of lead exposure to community members. She said the federal government also has to provide clear instructions to First Nations on how to deal with exceedances of the lead guideline. “Choosing the right solution, it’s not always as obvious as you might think,” she said.

| Which First Nations communities took part in this testing?

According to Indigenous Services Canada, the following communities took part in its 2017 sampling campaign: Ekuanitshit-Mingan Essipit Gesgapegiag Kahnawake Kanesatake Kebaowek Kitcisakik Kitigan Zibi Lac-Simon Listuguj Long Point Manawan Mani-Utenam Mashteuiatsh Matimekush-Lac-John Nutashkuan Odanak Opitciwan Pakuashipi Pessamit Pikogan Rapid Lake Timiskaming Uashat Unamen Shipu-La Romaine Wemotaci Wendake Wôlinak |

With files from Shushan Bacon (APTN News); Michael Bramadat-Willcock and Thomas Delbano (Concordia University); and Declan Keogh (Institute for Investigative Journalism)

Investigative team:

Institute for Investigative Journalism:

Lila Maître (fellow)

Université du Québec à Montréal:

Philippe Julien-Bougie, Geneviève Larochelle-Guy, Lila Maître, Bruno Marcotte, Étienne Robidoux (Instructors: Patti Sonntag and Jean-Hugues Roy)

Translated by Laurence Brisson Dubreuil

Produced by the Institute for Investigative Journalism, Concordia University

See the full list of “Tainted Water” series credits here: concordia.ca/watercredits