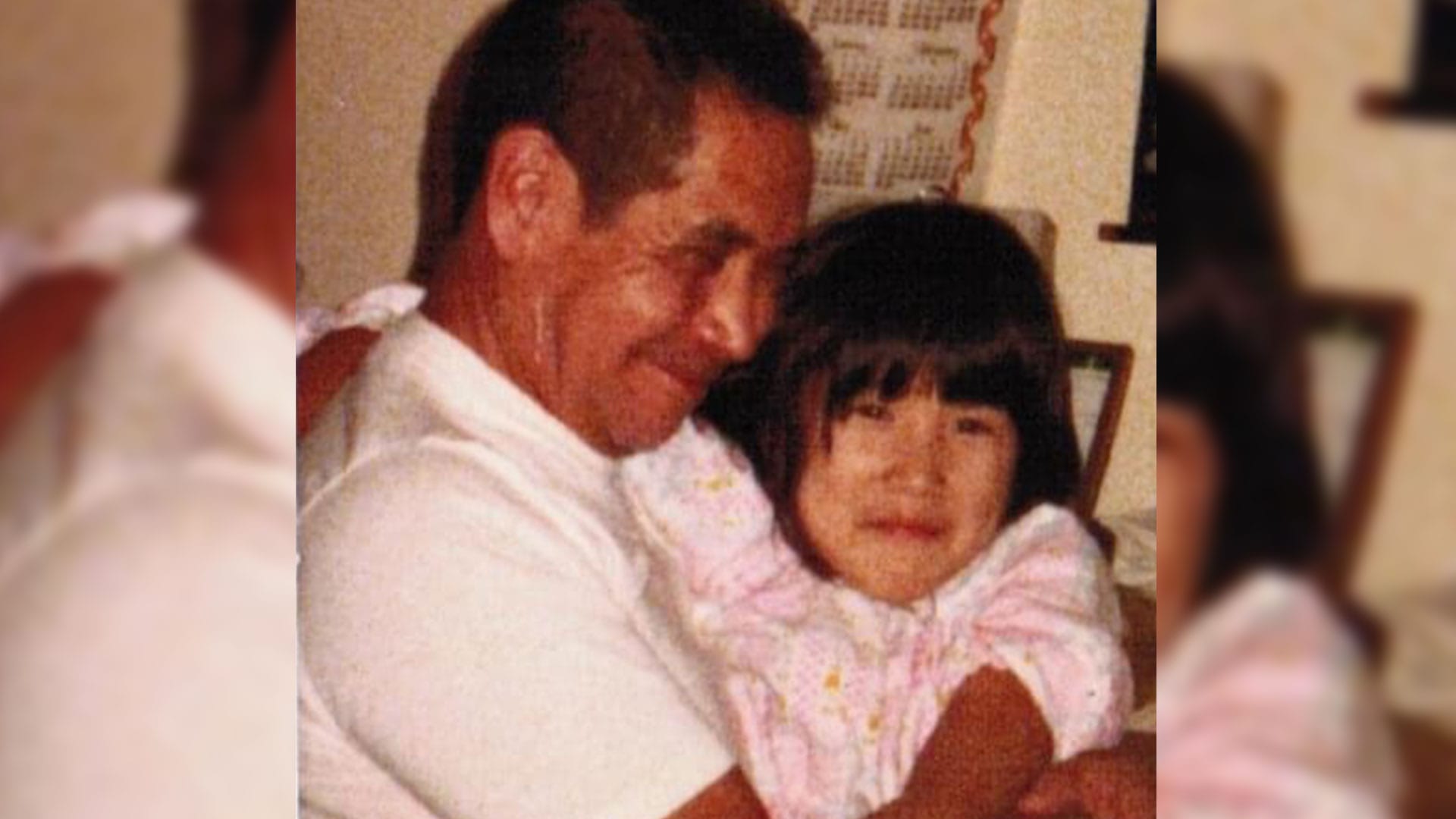

Taaʔisimqa Leona Smith, teaching nurse from Ehattesaht First Nation. Photo provided by Taaʔisimqa Leona Smith

After Taaʔisimqa Leona Smith graduated from high school, it was her grandfather who encouraged her to pursue a career in nursing.

Taaʔisimqa’s grandfather Cecil Smith, of the Ehattesaht First Nation, wanted her to be able to take care of herself, she says, and helped to guide her career.

“He kept reminding me that I needed to continue on with my education,” she says. “A high school diploma was not going to be enough. I was a janitor at the time and 19 years old.”

Taaʔisimqa has been working as a nurse for the past 22 years, with a master’s degree of science in nursing. She became a residential care aide when she was 20, and has since taught at three universities.

As a Registered Nurse, her current role is as a professional practice leader, supporting nurses with their educational needs. She works under the Office of the Chief Nursing Officer at First Nations Health Authority (FNHA).

This past year’s ongoing pandemic has been especially difficult for frontline workers, bearing the impacts of COVID-19. Taaʔisimqa shares her respect to other healthcare workers.

“I really hold my hands up to colleagues at FNHA, and to those on the ground, especially in this past year,” she says. “We’re working at full capacity — and still whole-heartedly.”

Taaʔisimqa is Nuu-chah-nulth (from Ehattesaht and Ahousaht) on her mother’s side and Chinese through her father. She grew up in the Ahousaht community with a strong sense of identity, she says.

Growing up in the ‘70s, she faced racism on both sides of her heritage. In light of increased anti-Asian discrimination during COVID-19, she has been especially moved to stand proud in who she is.

“In our pandemic world, I wanted to honour that piece, stand in my strength as an Indigenous and a Chinese woman,” she says.

When the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC) released its final report and Calls to Action in 2015, Taaʔisimqa was working on FNHA’s agreements with nursing programs. She took the moment as an opportunity to advocate for cultural safety training in nursing programs.

She has since been involved with various working groups and steering committees to integrate the TRC recommendations, specially calls to action 18-24 regarding health, into the nursing curriculum.

In 2019, she was the only Indigenous nurse in a working group with the BC College of Nurses and Midwives — the licensing and regulatory body for nurses and midwives in B.C.

The group has worked to introduce cultural safety, humility and trauma-informed practice as an entry-level competency for all nurses in the province, she says. Taaʔisimqa says because Indigenous Peoples are overrepresented in the healthcare system, it’s especially important for nurses to have cultural competency.

“[Nurses] need that minimum knowledge of history of First Nations people: residential schools, Indian hospitals, ‘60s Scoop, missing and murdered Indigenous women, the In Plain Sight report,” she says.

“It’s slow momentum, like watching a slow train, but it’s getting there.”

Her work includes bringing lived experience and Indigenous knowledge and wellness perspectives into balance with academia. It’s a dynamic she struggles with personally, and in her work to seek an equal balance.

“I really struggle between the two worlds of academia and lived experience, because that’s not how our people work,” she says. “We don’t have to reference everything or look it up. Our research is our knowledge keepers. So I’m trying to find balance with those two worlds.”

Taaʔisimqa takes her role sitting at these “larger tables” seriously, and although she doesn’t presume to speak for all Indigenous people, she can use her experience to advise on cultural safety training for nurses.

“My dream is in five years cultural safety and trauma informed training are not elective or optional — they would be mandatory. Right now only a handful of nursing programs now do mandate,” she says.

“It’s a matter of that slow train. Trying to get people on board, and knowing this is what is going to work.”

May 10 to 16 is National Nursing Week in Canada, which recognizes the courage and commitment that nurses bring to their work. For Indigenous nurses, this commitment is twofold, as they are also leaders in navigating and transforming colonial systems.

Throughout the week, IndigiNews will feature Indigenous nurses across generations and celebrate the many intersections of diversity that they bring to the healthcare system.