I meet up with Robert Doucette at the University of Saskatchewan Archives in Saskatoon. He’s running late because he has to drop his daughter off at school, it’s something the 56-year-old father of four takes great pride in.

“Family is the most important thing to me,” he tells me. “And I think, within our own communities, that has always been the most important thing. That’s why they targeted it.”

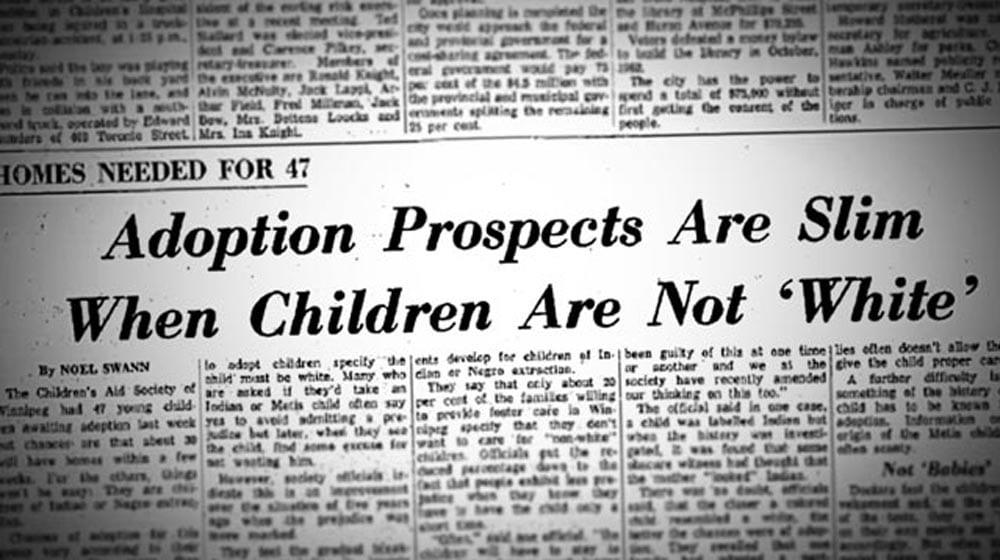

(Winnipeg Free Press)

Doucette’s name was the first to pop up when I began researching Métis Sixties Scoop survivors for an upcoming documentary I’m producing for APTN Investigates.

As the former president of the Métis Nation of Saskatchewan, he has been very vocal about the treatment of Métis survivors over the years.

“We’re the ‘just wait’ tribe, the ‘just wait’ Aboriginals,” Doucette says. “And I’m educated enough and motivated enough and strong enough to say, I’m not accepting ‘just wait.’ None of us should. Just deal with the issue.”

Classes have just started back up for the semester and the campus is alive with students going about their daily routines as we slowly make our way down a number of hallways before eventually descending into the archives.

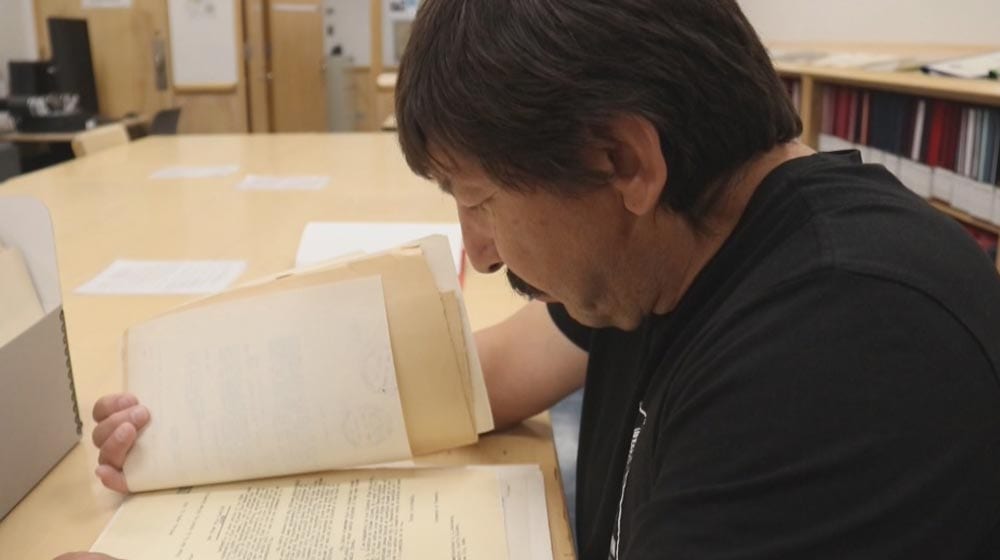

(Robert Doucette in the University of Saskatchewan Archives. Photo: Cullen Crozier/APTN)

Doucette spends a lot of time in libraries and archives like this one, going through boxes of old documents and files, slowly scanning hundreds of feet of microfiche, trying to find answers to questions about his past.

“You can see that, from the documents I’ve read and the research that I’ve done, that the goal since day one, of both of these governments is to assimilate and to integrate Aboriginal people, Métis and First Nations people into what they believe,” says Doucette. “They didn’t take any time to try and understand our cultures.”

Like many children of his generation, Doucette is a victim of the Sixties Scoop – an archaic nation-wide adoption strategy that saw tens of thousands of Canadian Indigenous children removed from their families and placed in non-Indigenous homes.

(McKay family photo, Buffalo Narrows Saskatchewan circa 1960. Photo courtesy: Robert Doucette)

Doucette was apprehended by child welfare workers from his home community of Buffalo Narrows, Saskatchewan in 1962 – he was only four months old.

His biological mother, Dianne McKay, was just 15 years old when he was born and while his immediate family was more than willing to take care of the newest addition to the family – social services had other ideas.

“So you have a 15-year-old, unwed Métis girl in the middle of a northern Saskatchewan forest with a baby boy and seemingly, according to their belief, no support system,” Doucette recalls. “They didn’t understand the extended family system, my auntie, my mushom and kokum were all there to help.”

To this day, neither Doucette nor his biological mother have ever been given a reason why he was taken away.

(Robert Doucette, photo taken shortly after he was scooped in 1962. Photo courtesy: Robert Doucette)

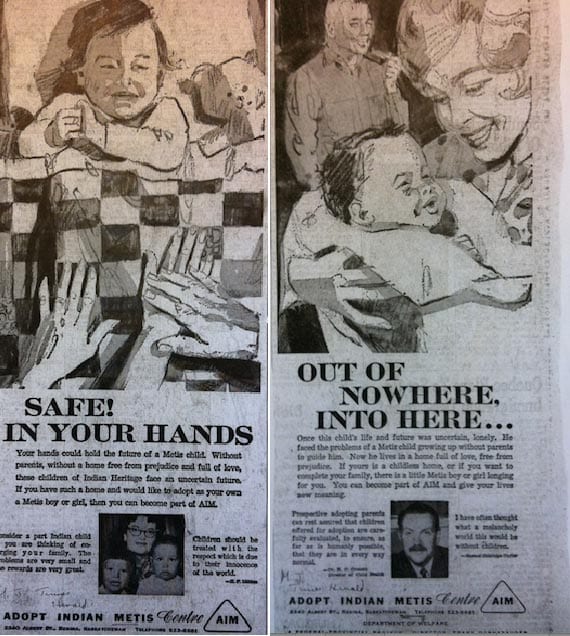

While each province developed their own policies regarding the adoption of Indigenous children during the height of the Sixties Scoop, Saskatchewan had a somewhat uncommon approach – they hired an advertising agency to help sell the idea to the public. The program was called Adopt Indian Métis or AIM.

“The AIM program has had a devastating impact on our communities and now we are having to deal with that,” Doucette tells me as he pulls out a file folder thick with old AIM newspaper clippings he has collected over the years. “They’ve done a real number on a lot of families and caused a lot of harm and now it’s our generation that has to try and pick up the pieces and raise our families the best that we can.”

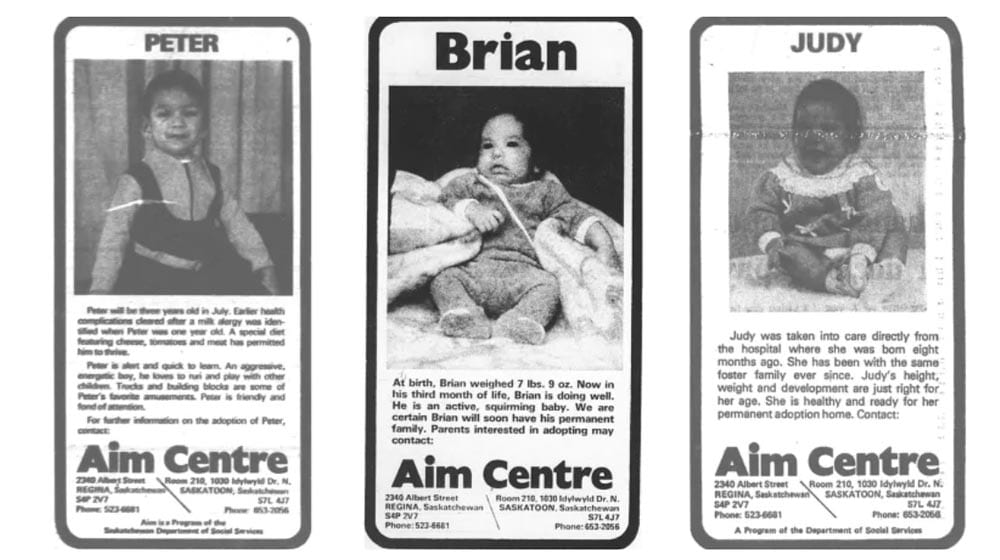

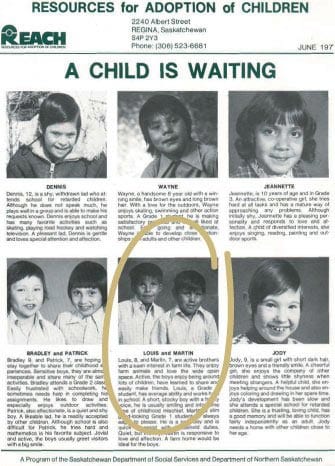

(Newspaper advertisements for the Adopt Indian and Métis Program, late 1960s, Saskatchewan.)

The AIM campaign was simple yet extremely effective.

Beginning in 1967, the pilot program was funded by both the federal and provincial governments who wasted no time inundating residents of Saskatchewan with public service announcements, newspaper advertisements and television and radio spots – all meant to stimulate the public interest in transracial adoption.

Watch: Cyril MacDonald – Saskatchewan’s Minister of Welfare 1967

To get a better understanding of how the AIM program came about and the impact it had on the Sixties Scoop, I travelled to the University of Regina to meet with historian Allyson Stevenson.

As a Métis adoptee, Stevenson has a personal experience with Saskatchewan’s child welfare system. She wasn’t scooped but was voluntarily given up for adoption by her birth mother.

“Initially, being a Métis adoptee is what drew me in to understanding the Sixties Scoop,” Stevenson tells me from the Aboriginal Students Centre on the U of R campus. “I recognize the experience and continue to be deeply engaged in issues around social justice in regards to the child welfare system.”

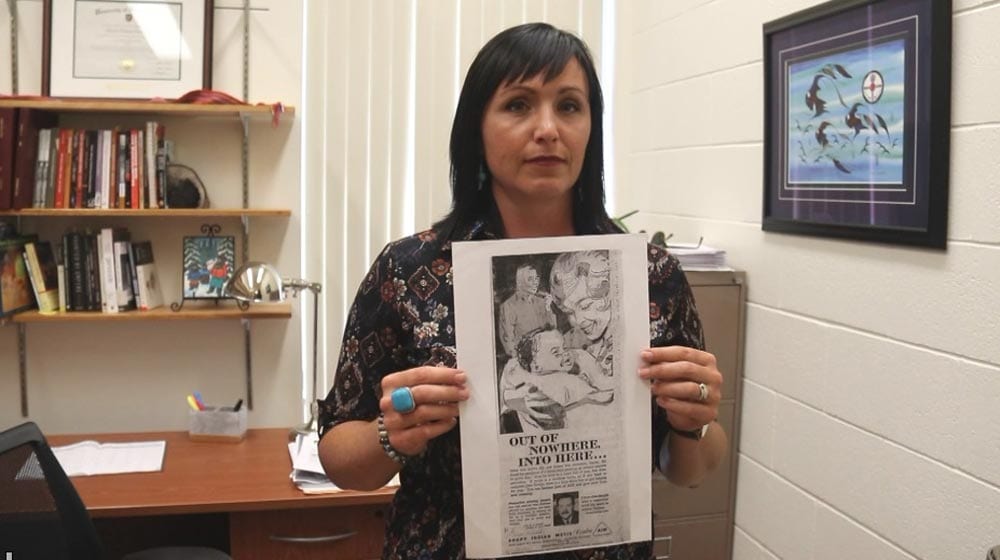

(University of Regina historian Allyson Stevenson. Photo: Cullen Crozier/APTN)

Stevenson says that in order to understand how the Sixties Scoop came about in Canada and how it was allowed to thrive for decades afterwards, you have to understand the racism and prejudices that Indigenous people faced on a daily basis.

“There was a century of racial bias on the part of many non-Indigenous families in Saskatchewan, in Canada.” Stevenson says. “It’s no secret that First Nations and Métis people were perceived as less than white. White supremacy was very common in Canada.”

The official reasons that were given for having children taken from families are eerily similar to today – poverty, poor housing, addictions and family break up being some of the most common.

As for the AIM program itself, Stevenson says that it was strictly to advertise First Nations and Métis children as needing families and as detached from their home communities.

(AIM Advertisement. Regina Leader-Post and Saskatoon Star Phoenix)

“The narratives were meant to ease any anxieties around Indigenous identities or racialized fears that Canadians, non-Indigenous people might have about taking children in,” Stevenson said.

“The children would be dressed in very middle class attire and the descriptions would play up their desirability. For girls they would be described as very loving or very quiet, likes to play with dolls. For boys it would be, fun little guy, likes to play with cars and so on,” she adds.

To this day it’s still not known how many Indigenous children were victims of the Sixties Scoop.

From the late 1950s to the mid-1980s it’s estimated that more than 20,000 Indigenous children were scooped up from their families and home communities and fostered or adopted out into non-Indigenous homes. But even those numbers are considered conservative.

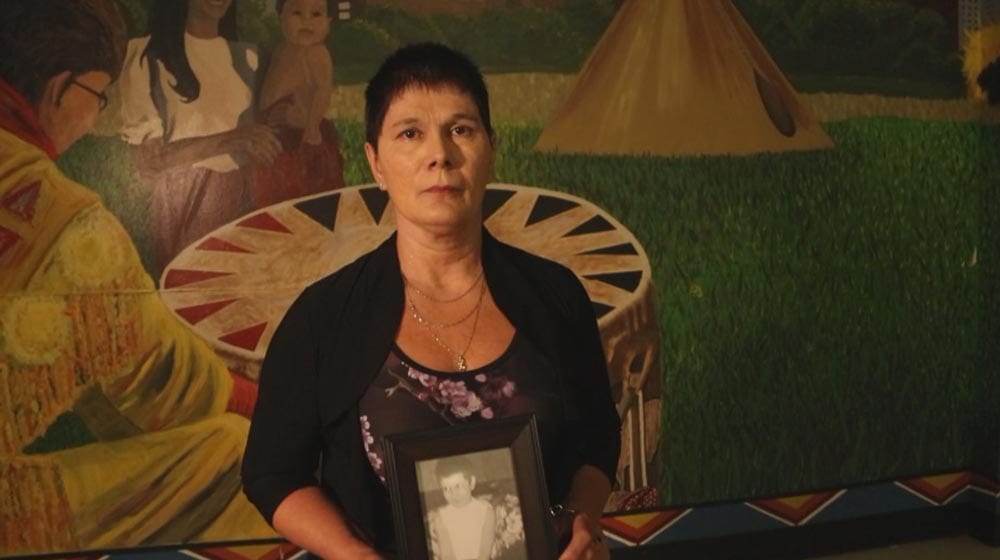

It’s just one of many unanswered questions that survivors like Dr. Jacqueline Maurice want answered.

“Being a child of the sixties scoop, it’s like I was ready to die of a broken heart,” says Maurice. “It’s such a loss, it’s like the loss of a limb that can never be replaced.”

(Dr. Jacqueline Maurice. Photo: Cullen Crozier/APTN)

Maurice suggested we meet at the Batoche National Historic Site just outside of Saskatoon because of the significance the battlefield holds for the Métis people. I arrive an hour early and find that she is already there waiting for me.

She greats me with an apprehensive smile and presents me with a small medicine bag filled with stones and sage as a token of her appreciation for me covering her story. It’s a gift that I humbly accept.

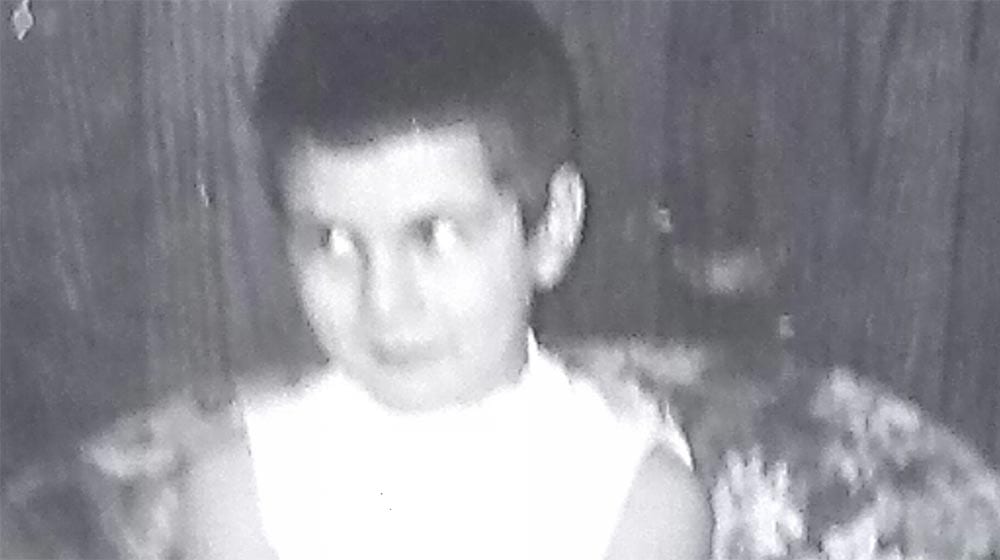

Like most of the survivors that I spoke with, Maurice had a very devastating experience with the Sixties Scoop. She was taken right at birth from Meadow Lake Union Hospital and made a permanent ward of the government. She was never registered for adoption and as a result grew up in the child welfare system.

(Only known photo of Jackie Maurice as a child. At three years of age, she had already been through nine foster homes. Photo courtesy: Dr. Jacqueline Maurice)

“At age four, I was in a holding area, kind of in a warehouse area at Dale’s House in Regina,” she tells me. “Dale’s house at that time was a juvenile delinquents centre. So I often ask, what is a three-and-a-half, almost four year old child, young girl doing in a juvenile delinquent centre? And that was my first recollection and memory of being sexually assaulted.”

Maurice would spend the next decade being bounced around from foster home to foster home, never finding the love and support of a family that she desperately longed for. By the age of 15, she had already made a number of attempts on her young life.

“I was just so devastated after my final and 14th foster home that I didn’t know where to turn to,” Maurice recalls, holding back tears. “And no young person in their life should be faced with that decision. I want to make that clear. So from that age on, I literally had the backing of no family. Not that I had family in my life anyway.”

(Dr. Jacqueline Maurice. Photo: Cullen Crozier/APTN)

Maurice ended up on the streets. She was forced to lie about her age in order to get a part-time job to put a roof over her head. She spent the next few years trying to drown her past in a bottle.

“I was at all those crossroads,” she continues. “Jails, institutions, death, alcohol, self-destruction, hitting the streets, violence, you name it. Because I was not only family-less but when you grow up in the system, you’re pretty much homeless in a lot of respects.”

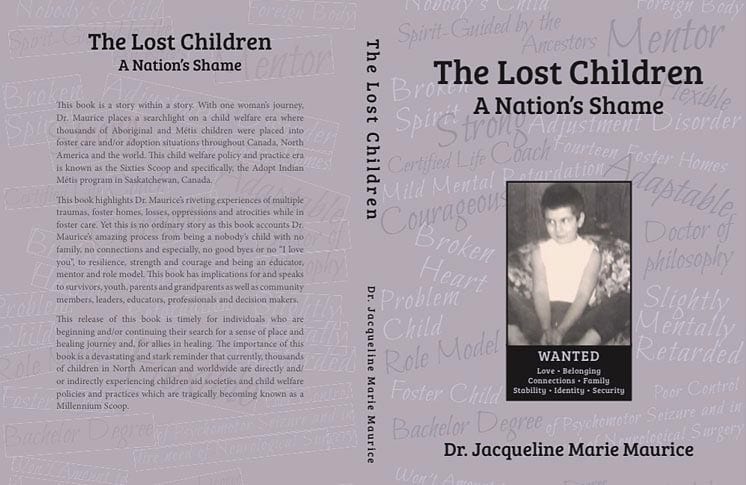

Maurice eventually found the strength to turn her life around. She put herself through university, achieving a PhD in social work. She even wrote a book, “The Lost Children: A Nation’s Shame” chronicling her life caught up in the child welfare system.

“We often say that it takes a whole village to raise a child.” Maurice says. “And in terms of my own health and wellbeing I had to learn to let it go and draw strength from the positives and really step into the spirit of forgiveness.”

(The Lost Children: A Nation’s Shame by Dr. Jacqueline Maurice)

While Maurice was eventually able to come to terms with her past, other survivors weren’t as fortunate.

By the time the 1970s rolled around the AIM program was well established in Saskatchewan. Provincial statistics showed that the program was a success and that the number of Indigenous children adopted out to non-Indigenous homes was on the rise.

But with all of the new found attention also came notoriety.

(A 1975 Government of Saskatchewan adoption services poster)

As the AIM program reached its height of success, the Métis community also began to take notice. Grassroots organizations like the Métis Society of Saskatoon began to demand that Indigenous children be returned to their families or, at the very least, be adopted out into Indigenous homes.

It’s was a turning point in history that Senator and Elder Nora Cummings remembers all too well.

“This is Canada for God’s sakes,” she says. “This is our home and we’re treated like a Third World country.”

Cummings invites me up to her small apartment on the outskirts of Saskatoon. She answers the door with a warm smile and offers me tea and bannock.

(A touch of Métis hospitality. Photo: Cullen Crozier/APTN)

Cummings is something of a legendary figure within Saskatchewan’s Métis community and at 80 years of age she isn’t afraid to speak her mind.

“I would have died before I let them take my children,” she tells me. “And you know, I was blessed that I had all of my children.”

Cummings never had any of her children taken during the Sixties Scoop – but it wasn’t for a lack of trying. She still remembers the day that she was sent to meet with a director for the department of Social Services in Saskatoon.

“He had his feet up on the desk,” she remembers. “And he said, ‘we’ll maybe let you keep two oldest, we’ll take the twins and take the baby when it’s born.’ And I got really upset, very emotional, I said, those are my children that you’re talking about, and nobody’s going to take my children or my unborn child.”

Cummings tells me her story with such passion and intensity, that I can only imagine how the social worker must have felt – like an unruly child being given the scolding of a lifetime.

“And let me tell you something else,” she continues. “If you send a social worker to my house, they’re not going to walk out of the house with my children, they’re not going to walk out. And I said if you think I’m kidding, you try me.”

(Senator, Elder Nora Cummings at her home in Saskatoon. Photo: Cullen Crozier/APTN)

Social Services never bothered Cummings or her children again after that encounter although her sister wasn’t as fortunate – she had five of her children taken away and adopted out.

“We never knew what happened to them,” Cummings tells me. “We lost track and when my sister got her life together she went back into court and they wouldn’t give back her children. They refused, even with all the support she had from her family.”

Her sister never recovered from the loss and when she passed away, Cummings made a promise to their mother that she would find all of the children that were scooped.

In the years that followed she began to lead a growing resistance of Métis women and families seeking to put an end to the AIM campaign once and for all.

(Senator, Elder Nora Cummings rests her hand on a Métis sash. Photo: Cullen Crozier/APTN)

“We told them, you have to take these ads away,” Cummings says. “So we did, we stopped that, we got that stopped. We got them to stop taking children over the border. And we had good support, we were in the communities and everyone was organizing and our women were very vocal because we had to be. We had to be vocal and radical in a sense because women weren’t respected.”

Cummings also managed to keep her promise and was eventually able to track down all of her sister’s children that were scooped. And while it may not have been the reunion that she had imagined, Cummings says that they are rebuilding their relationship one day at a time.

“For me, my sister and I were very close and our children were very close together,” she tells me. “And now they don’t have that connection and that saddens me. We’re kind of strangers and we’re still working on that relationship. You know people don’t understand, it doesn’t only affect the parents, it affects the whole family.”

(Senator, Elder Nora Cummings holding an AIM advertisement. Photo: Cullen Crozier/APTN)

The government policies that led to the administration of the Sixties Scoop were discontinued in the mid-1980s. In the years that followed, multiple lawsuits were filed against the Government of Canada by the survivors.

On October 6, 2017 an $875 million settlement was announced for First Nations and Inuit victims. Métis and non-status survivors have been excluded from the agreement.

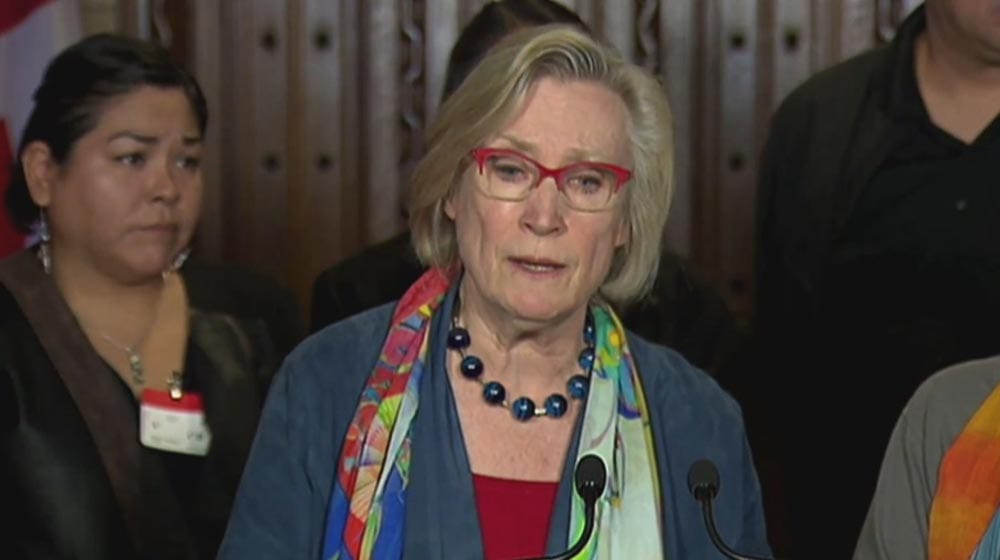

(Carolyn Bennett, Minister of Crown-Indigenous Relations announcing settlement.)

Before leaving Saskatoon to begin work on the documentary, I pay a final visit to Robert Doucette at his small suburban townhome.

He lays out a number of family photo albums for me to look at, many of which show him with his adoptive family, the Doucette’s in Duck Lake Saskatchewan, where he was raised.

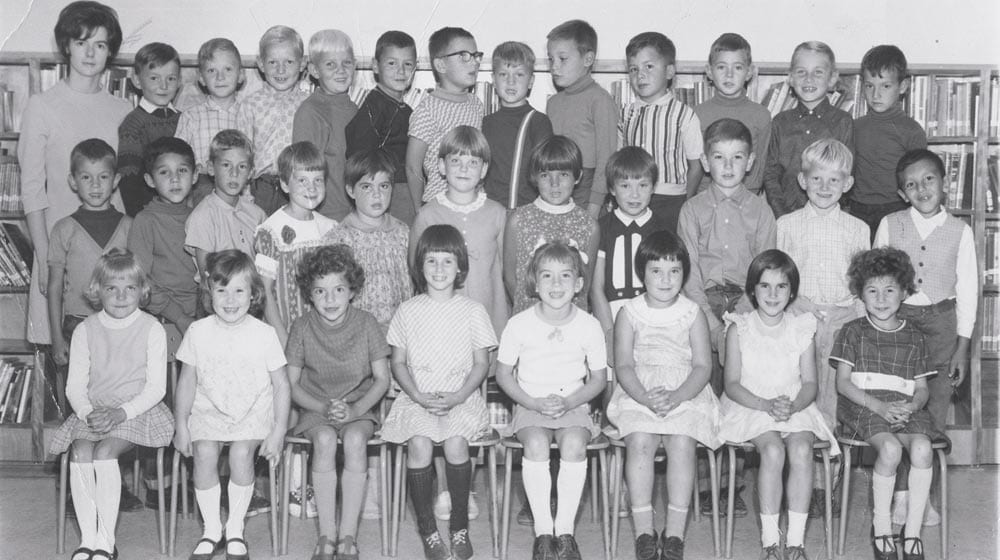

One of the photos shows a class of dozens of smiling youngsters with Doucette off to the side, head cocked at an awkward angle to the right – the result, he tells me later, of a hasty forceps delivery that permanently damaged the nerves in his neck.

(Elementary School photo. Robert Doucette middle row, far right. Photo: Robert Doucette)

Another shows Doucette at his adoptive sister’s wedding. Again he is seen standing off to the side, seemingly uncomfortable in his own skin.

(Doucette family wedding. Robert Doucette far left. Photo courtesy: Robert Doucette)

“Basically we thought we were white,” Doucette remembers. “But yet we’re being called chief and Indian, right? So it really plays a role in how you view yourself and as I got older it became more intense, the racism and the ugliness.”

But it’s that history and shared experience that has led Doucette to help other Sixties Scoop survivors at various sharing circles throughout Saskatchewan. The stories are usually very painful but Doucette says that it’s all part of the healing process.

“In some of these homes, the children were used as slave labour on farms,” Doucette recalls. “One gentleman told me that they were lined up just like cattle and they would look at their teeth and their eyes and inspect them like they were animals and then point out which ones they wanted.”

Doucette closes the photo albums and carefully places them back on the shelf.

“These are the stories that a lot of non-Indigenous Canadians have never heard,” he finishes. “And it shocks them.”

After hearing all these stories and seeing for myself the pain behind them, I’m thinking they should be shocked.

It didn’t matter as lo g as our people metis statues or no statues we were all taken And the changes they tried to do with us was horrible we could talk or look like an Indian punishments we felt and still feel today is no excuse for another human being to take and treat us as children from another race We all felt the sadness and tears that were silent and still are finally we can talk please everyone brother and sister in our native community let’s finally talk

It didn’t matter as lo g as our people metis statues or no statues we were all taken And the changes they tried to do with us was horrible we could talk or look like an Indian punishments we felt and still feel today is no excuse for another human being to take and treat us as children from another race We all felt the sadness and tears that were silent and still are finally we can talk please everyone brother and sister in our native community let’s finally talk