With Jordan Tootoo, the first Inuk to play in the NHL, calling it home, Rankin Inlet is known for hockey.

They’re also known for the volunteerism it takes to host and promote visiting hockey teams.

When COVID-19 fears caused Nunavut to shut down in March, the community turned that volunteerism toward making sure Rankin Inlet was ready for when the virus hit Nunavut.

“Volunteerism here is really amazing,” explained Rankin Inlet Mayor Harry Towtongie. “People were sewing masks, some for their own, and some to give away. They weren’t really selling them, just giving them away to relatives and friends.”

When facing something unknown like COVID-19, staying busy can help.

Rankin Inlet’s 2,800 residents took that idea to heart, and went well beyond sewing masks.

“They even took a course on how they’re going to handle these infected people, and 30 is a lot for volunteers,” said Towtongie.

According to Premier Joe Savikataaq, that’s just how Rankin Inlet gets it done.

“They’re pro-active, and that’s a good thing. It’s always better to be pro-active to a problem than reactive. So I commend them for what they did,” he said.

The community arranged for two unused hotels to be made available for people who would have to self-isolate if they had COVID.

Like all Nunavut communities, Rankin Inlet has a terrible housing crisis and it’s very hard to isolate under overcrowded conditions.

They even went as far as making a plan to convert their new – much beloved – hockey arena into a temporary hospital if need be.

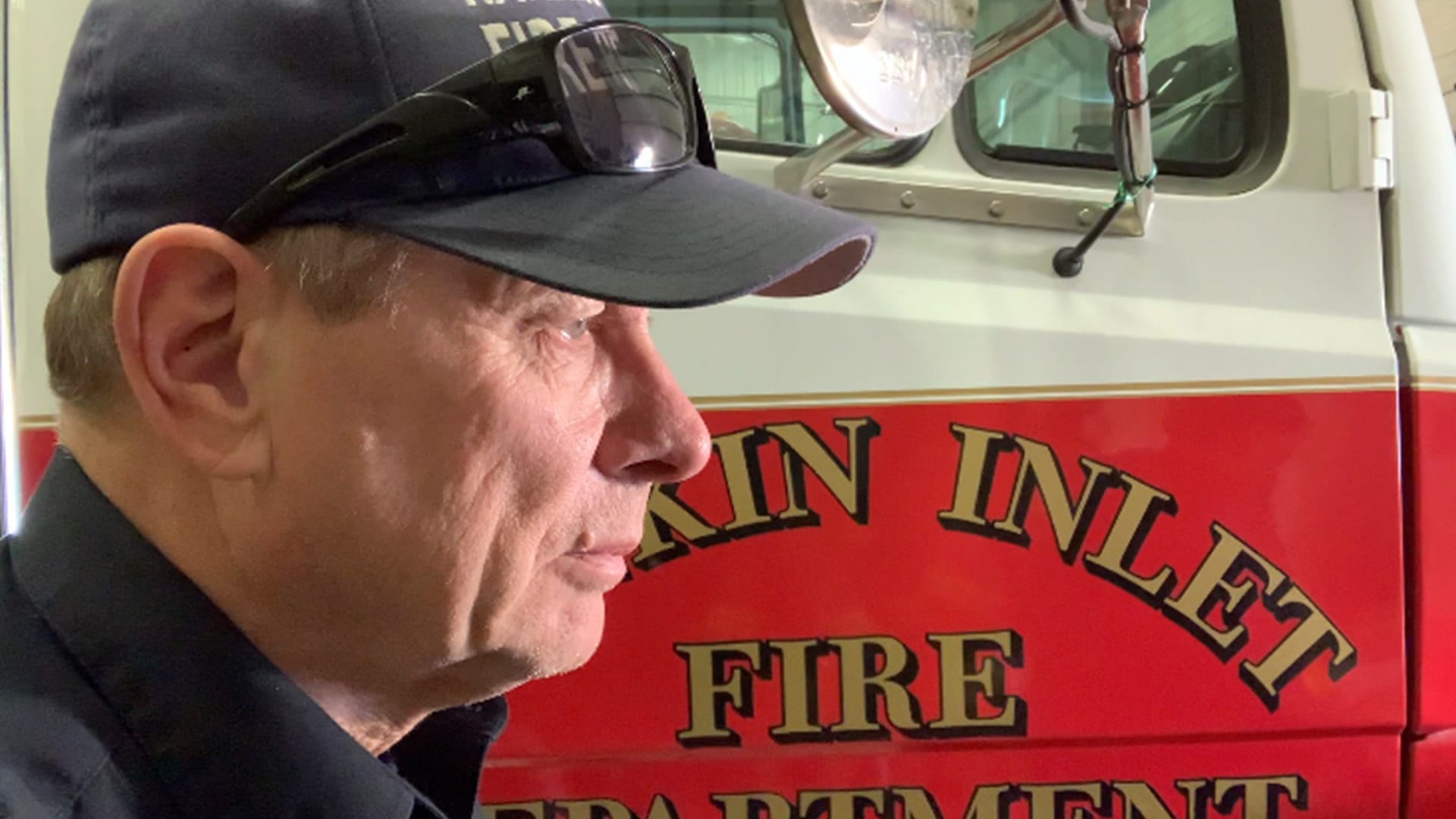

Mark Wyatt is Rankin Inlet’s fire chief.

“We had isolation hubs, we had the arena earmarked for a temporary field hospital, a plan with volunteers to man those hubs, pretty much everything,” he said. “The challenge here is obviously, if COVID did come, I know houses that have 20 people in them.”

Near Rankin Inlet is the Meliadine Gold Mine, a major employer in the community, and a huge supporter of community causes.

It also employs many people from outside Nunavut – and that is where the problem arose.

After COVID fears were high – but before Nunavut officially cracked down on outside visitors- a planeload of workers arrived to go to the mine.

The airport is in Rankin Inlet, you have to go through Rankin to get to the mine.

So residents drove to the mines gate and formed a blockade, they weren’t going to risk letting COVID in.

“People took it into their own hands,” said Towtongie. “I don’t really blame them. I think they might have got the mine thinking of how to find a way to do this, and I think they actually did.”

That protest, and similar concerns across the territory, led all of Nunavut’s mines to adopt a COVID policy.

If you live in Nunavut but work at a mine, you would receive 75 per cent of your pay to stay home.

The mines got to operate with southern labour, without risking the population.

The mines are in Nunavut, but not inside Nunavut’s COVID bubble.

Nunavut’s Finance and Justice Minister George Hickes did point out that while the Rankin Inlet reaction was quick, there was a huge potential problem.

“I remember when that circumstance happened, when they closed the mine, after a plane had landed with a crew change, the crew was trying to get to the mine. If they turned back from the mine, there’s nowhere left to go but town,” said Hickes.

Now, the worries of Rankin have come to light.

After seven months of being virus free, Nunavut now has cases.

As of Nov. 18, there were 70 positive tests, eight of them were in Rankin Inlet, another 54 are in Arviat, and eight are in Whale Cove.

Whale Cove and Arviat connect directly to Rankin Inlet by air.

They haven’t had to active the arena to hospital plan yet. When APTN News visited Rankin Inlet in October, before travel restrictions made that impossible, Towtongie was asked what would happen if a case arrived.

“If it happens,” explained Towtongie, “we’ll shutdown and people will listen and do their best like they have. We need to listen to the doctors and the people who are running the Covid situation.”

The Fire Chief agrees.

“I think, first case in Rankin, everything will shut back down again,” explained Wyatt. “We will start social distancing, and if you told everybody to wear a mask tomorrow, you’d have a mask on every single person in Rankin.”