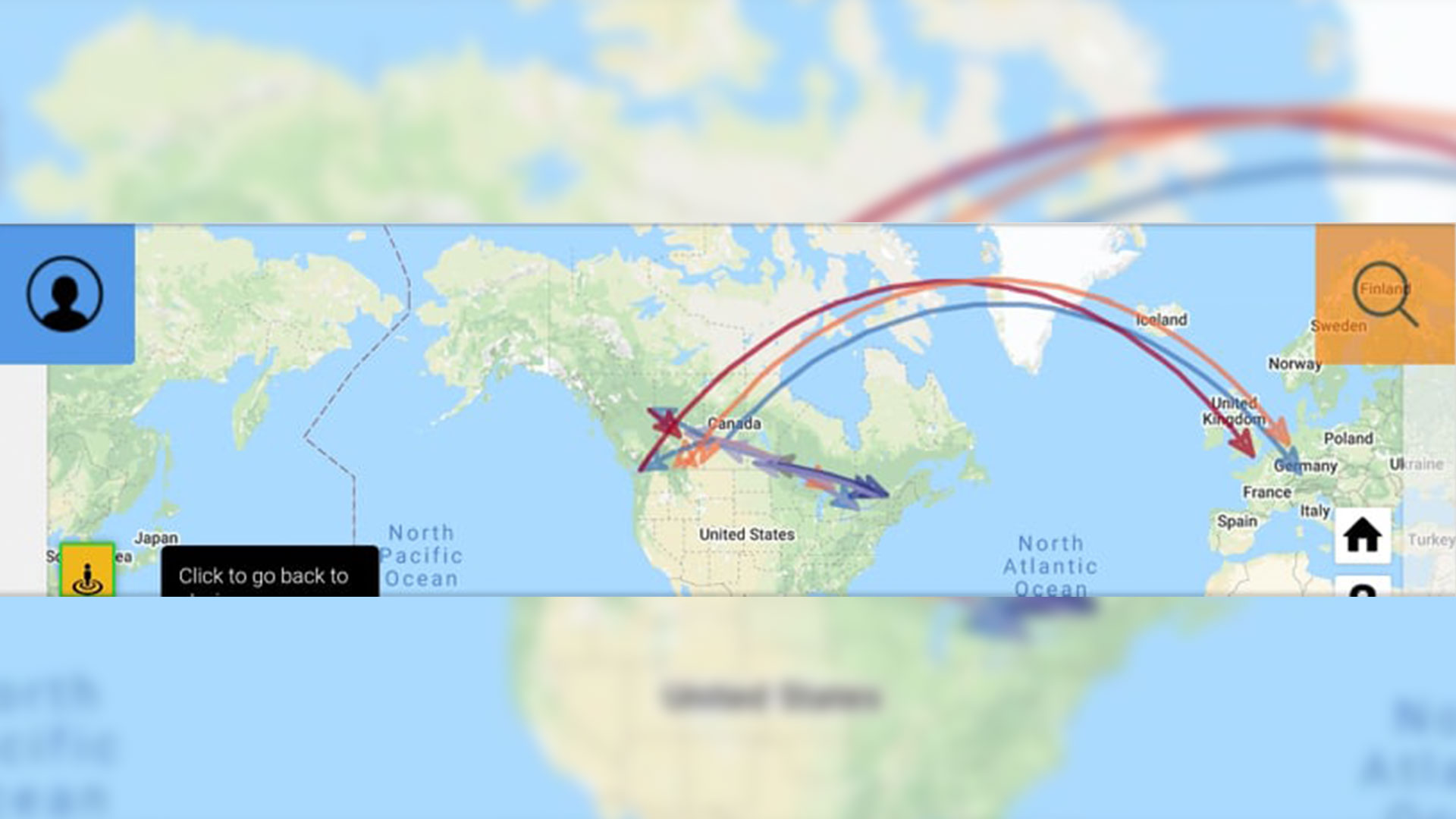

A new digital project maps the displacement of '60s Scoop survivors. APTN

Colleen Hele-Cardinal knows Indigenous adoptees like herself left invisible trails across the earth as part of the so-called ‘6os Scoop process.

As an artist, she wanted a way to illustrate those journeys for Canadians and the world.

So she created In our Own Words – Mapping the 60s Scoop Survivors Diaspora that went live this week.

“We are going to use a colour code for each province as a point of origin, then identify where survivors were subsequently fostered or adopted,” Cardinal said from Ottawa Monday.

“For example, Indigenous children taken from B.C. would be identified using red, Alberta green, Saskatchewan yellow, Manitoba orange, etc.”

The digital map shows in striking detail how children were displaced from their traditional homelands and territories and raised in non-Indigenous places and ways, she added in a release.

“The scope of this project is international and our goal is to make the map go viral and receive as much user traffic as possible for it to become a visual tool to represent our truths.”

Hele-Cardinal is co-founder of the Sixties Scoop Network and has organized four national ‘60s Scoop survivor gatherings.

She is also collaborating with University of Regina professor Raven Sinclair’s Pe-kīwēwin project, which is researching policies that have put so many Indigenous children in care.

The ’60s Scoop occurred between the late 1950s and early ‘80s. More than 20,000 First Nations, Inuit and Métis children were apprehended by provincial child welfare agencies and placed in non-Indigenous foster homes or for adoption.

As the interactive map shows, they were sent to locations across Canada, the United States and overseas.

What makes it interactive is that adult survivors can input their own journeys into the system.

“They have the option to share as little or as much information about themselves as they want,” Hele-Cardinal said, “as well as short videos, pictures and a short narrative of themselves.”

Along with tracing their routes, the map can be used to connect with family members, friends and communities.

“It is our hope to include resource information that can be accessible to survivors through our platform,” Hele-Cardinal said in the release.

“This project will also enable researchers and communities to produce statistical data on the 60s Scoop and identify which geographical areas Indigenous children were taken from and where these children ended up.”

Survivors have the option of removing identifying visual data from the platform at any time. But their information remains the property of the project for statistical purposes.