After a landslide devastated the migrating salmon population in the Fraser River in 2018, Fisheries and Oceans Canada says numbers appear to be rebounding.

Officials working on the Big Bar Landslide Response said 280,000 salmon passed through sonar upstream of the site as of Aug. 9, including 234,000 Sockeye and 45,000 Chinook.

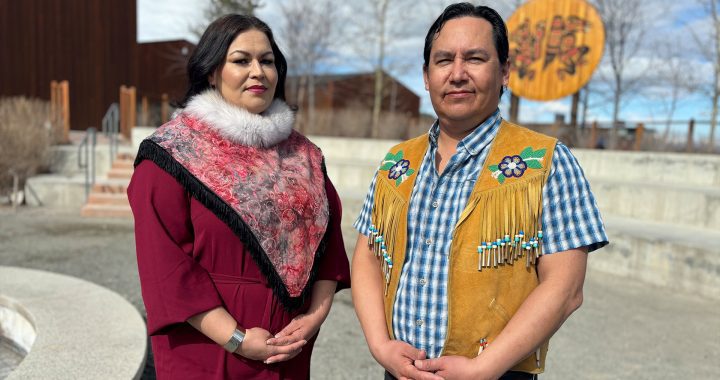

“People will eat this year up above the slide,” said Greg Witzy, a member of Cstelnec’ (Adams Lake Indian Band) and Indigenous project director for the Fraser Salmon Management Council, which represents 76 First Nations along the river.

“It’s important – not just to Indigenous people – (but to) everybody who relies on the Fraser. And especially those who don’t have a voice, like the salmon themselves, the eagles and the bears, and everything that depends on that life continuing.”

When 110,000 cubic metres of rock sloughed off a canyon near Lilooet, B.C., it created a five-metre high waterfall that prevented migrating salmon from reaching their spawning grounds.

Since the landslide was discovered in 2019, scientists, governments and First Nations have been working to conserve and monitor the fish that were already facing historically low numbers.

Gwil Roberts, director of the Big Bar Landslide Response with Fisheries and Oceans Canada, said 39,000 fish are passing through the site daily despite a slow start earlier this year.

He noted salmon were held back at areas along the river due to high water volume caused by late melting snow packs, though they were eventually able to get through.

He said forest fires during the summer of 2021 also prevented scientists from tagging as many fish as they hoped last year, though this year “is the opposite.”

“We have a tremendous number of tag fish moving through, and they’ve moved through at different times and at different flow rates, and different discharge rates throughout the canyon,” he told reporters during a virtual news conference.

Dale Michie, acting manager of biological programs for the response team, said scientists are focusing on conservation and monitoring efforts to better understand how salmon have been affected by the slide.

Those efforts include trapping the fish and transporting them upstream of the slide site, capturing fish by fishwheel, and radio tagging. So far, 741 salmon have been tagged.

“The monitoring is a very key component to understanding what remains to be the problem, if there is still a problem at Big Bar,” he said.

“We did see some improvements to what we saw last year, but still it’s very preliminary at this point, and we need the full analysis of all the tags that we have out there which will occur in the fall.”

Gord Sterritt, executive director of the Upper Fraser Fisheries Conservation Alliance, said the return of the salmon is a win for First Nations along the river that have been conservative in their approach to harvesting the salmon in recent years.

“It’s a positive experience whenever there’s fish that can return to the spawning grounds,” he said.