The College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario is the regulatory body for physicians in Ontario. They declined to refer the family’s complaint to a formal review hearing that may or may not have resulted in the physician being disciplined.

The parents of a then seven-year old Indigenous girl say their daughter was subjected to a traumatic forced genital examination due to what they believe was racial stereotyping by a northeastern Ontario emergency room physician.

“(The physician) had leaned her weight, her body weight on my child, was trying to get her legs open and I remember hearing my child objecting,” the girl’s mother said in a recent interview with APTN News. “(The doctor) was, at the time that I saw, attempting to pry her legs open. The only thing that really stands out is the look on my child’s face when it was over.

“Her face was red and her arms were crossed.”

APTN is not identifying the family, the physician, or the hospital in order to protect the child’s privacy. The child and her parents are the subjects of an anonymization order put in place by the Health Professions Appeal and Review Board of Ontario (HPARB).

The family complained to the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario (CPSO) shortly after the incident occurred in 2018.

HPARB is currently reviewing the matter at the family’s request, after the CPSO committee that screens public complaints did not refer the case to a hearing which that would determine whether or not the physician should be disciplined.

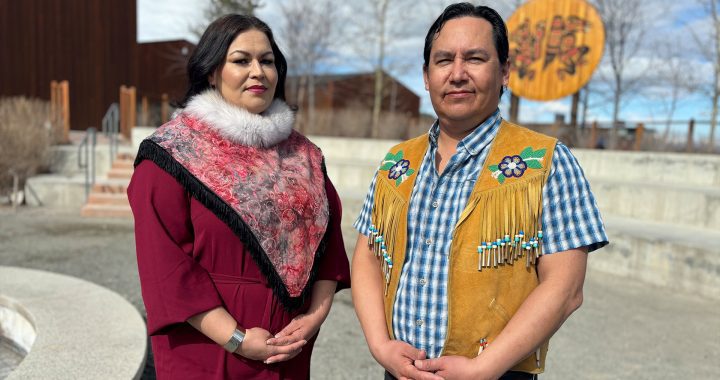

What Brittany Hobson’s TV story about the parents and the allegations

APTN asked for an interview with the physician but Keary Grace, one of her lawyers, declined on her behalf.

“(The physician) cannot comment on specific patient care. However, our position was set out in our submissions for the purpose of the Health Professional Appeal and Review Board hearing on May 28, 2020,” Grace said by email.

In that hearing, which APTN attended, another of the physician’s lawyers, Hakim Kassam, argued that the CPSO’s committee decision was reasonable and its investigation of the complaint was adequate. APTN asked them for the written submissions from the physician’s legal counsel but was denied access.

“The committee already had evidence that it was her standard practice,” Kassam said at the hearing. “This board should not interfere with the specialty of the college committee.”

The CPSO declined an interview request and said they were limited in what they could respond to about the specific case because of “restrictions under the Regulated Health Professions Act of Ontario.”

READ the full statement here:

The college sent a statement by email that said in part, “We take any allegations of systemic racism very seriously.”

“The CPSO is committed to doing its part to address systemic racism which continues to be a significant issue across the healthcare system.”

The complaint stems from the family’s visit to the emergency room of a northeastern Ontario area hospital in May 2018 after their daughter was showing signs of a urinary tract infection (UTI).

“I thought that if we went there we could go in and do a urine sample, get the prescription,” the girl’s mother said, adding that her daughter had repeated issues with UTIs due to a medical condition.

She said the physician kept asking repeatedly about a stomach ache even though her daughter said her stomach no longer hurt.

“So I asked he, ‘Excuse me, can we talk outside?’ Because I felt like I needed to answer the questions myself, because maybe she didn’t want to hear it from a child,” she said.

She says the physician then took her to a high-traffic area within earshot of other staff and patients.

The mother explained that anxiety could trigger stomach aches for her daughter, and explained the girl had experienced anxiety because of some incidents with her school bus driver who yelled at her, and that the family was already addressing those issues.

She said she then tried to redirect the physician back to checking the urine test results.

“Then she started asking me a line of questioning that was alarming,” she said. “’Do you and your husband fight in front of your child?’”

“She started to ask me whether or not my child had been sexually abused,” she said. “I became very afraid.”

After the mother told the physician that there were no concerns about abuse or problems in their home, she said that they returned to the room and the physician told her that she wanted to conduct a genital examination on the child.

Kassam submitted in the hearing that it was appropriate to ask screening questions about possible abuse, and that it was the physician’s standard practice to conduct genital examinations to look for sexual abuse on every child who presents with painful urination.

The mother’s lawyer argued at the review hearing that the CPSO should have verified that assertion by reviewing the doctor’s records, because different treatment of her daughter could suggest racial profiling.

The mother said she asked the doctor to check on the child’s urine test results before resorting to a physical exam but said the doctor explained that she was checking for a potential yeast infection though according to the mother there were no symptoms.

The girl’s mother, who has a background in social work, said she understands the need for child abuse screening but believes there was no reason to do so in this case.

“The only explanation for giving a domestic violence and sex abuse screening to someone with a UTI would be based on some sort of unconscious bias, in my opinion,” she said. “I became afraid and I felt that it was unsafe for me to object to an exam from a doctor that’s already suspicious of abuse.”

She believes the exam amounted to a sexual assault of her child because her daughter objected several times and refused to open her legs.

“My child objected many times,” the mother said. “At no time did my child consent to the exam.”

Kassam said in the hearing that the CPSO committee did consider consent and its decision included specific references to a ”slower-paced approach” and “better communication.”

Kassam submitted that the physician believed she had “implied consent” to the examination from the mother.

According to a CPSO statement not specific to this case:

“Informed consent is a fundamental principle of the physician-patient relationship and failure to achieve informed consent for sensitive examinations may in some circumstances constitute professional misconduct.”

The mother explained she tried to encourage her daughter to co-operate because she was terrified of what may happen if she refused.

“I was thinking: ‘What’s the lesser of two evils? Let her look? Or to have Children’s Aid come in and interview my entire family and go through Children’s Aid process,’” she said.

After the examination revealed no evidence of sexual abuse, the mother said the physician’s manner became friendlier and she wrote a prescription for a yeast infection cream.

The mother says that it was only after she then asked for a fourth time that the physician check the urine test results that the physician did so, finding that the child had a “glaring” UTI. She wrote a prescription for antibiotics, which alone cleared up the child’s symptoms.

The child’s father said that what he observed in the car ride home indicated that the incident was serious.

“My daughter, when we would get into our vehicles usually, she’d be yelling out orders,” he said. “She would want to hear kid’s tunes. Since that day, that hasn’t happened.”

He said his daughter was very quiet on the ride home and he noticed his wife’s usual upbeat manner changed.

“She was just sobbing,” he recalled. “Just trying to deal with what was going on, and I had no idea exactly what happened in the room. All I know is that it was pretty serious.”

In June 2018, the family filed a complaint to the CPSO shortly after the incident outlining several areas of concern including racial stereotyping, lack of consent and sexual assault.

After investigating the complaint, the CPSO’s Inquiries, Complaints, and Reports Committee declined to refer the matter to a disciplinary hearing that would determine if discipline was warranted — a process that could make the doctor’s identity and any decision public.

They found two lapses in care for a failure to provide a gown and draping during the exam and failing to order a urine culture in relation to the child’s UTI.

In January 2019, the CPSO reached a remedial agreement with the physician that required her to review the guidelines on ethical genital examination of children and review treatment protocols for UTIs in children.

Kassam said during the hearing that the physician was apologetic and demonstrated insights to voluntarily improve her practice, which does not support referral to the disciplinary committee.

The physician also completed an online Indigenous cultural training course at her own initiative.

“I was disappointed, to say the least, about the process,” said the girl’s mother.

The family sought a review of the decision by the Health Professions Appeal and Review Board, asking it to overturn the CPSO committee’s decision. That is when lawyer Sarah Beamish took on the case despite the family’s inability to pay legal fees.

She represented the family at a May 28, 2020 hearing which APTN attended.

Beamish said cases like this highlight the kinds of stereotyping and racial biases that Indigenous families experience when interacting with the medical system.

“It shows the heightened risk of interventions that harm them and their families,” she said.

During the public hearing, Beamish argued that the college’s investigation was not adequate and its decision was not reasonable. She notes that the lack of representation and resources available to the many alleged victims of medical harm make the processes very challenging.

“The family couldn’t do this alone. These non-court processes are supposed to be public-friendly but they are really difficult to navigate without legal counsel.” she said. “On the other side of it, you have the doctors in these cases who usually get specialized, high-priced legal counsel.”

Beamish said the family has also filed a complaint with the Human Rights Tribunal of Ontario, alleging racial discrimination. She said the HPARB review decision would be made in the next few months.

“It is a systemically unjust system toward Indigenous people,” the girl’s mother said. “The majority of families, Indigenous or not, would not be able to access this process. At least, not in a manner that’s fair.”

According to the legal submissions of the physician’s lawyer at the HPARB hearing, the investigation of the complaint by the CPSO committee was adequate.

“The investigation need not be perfect,” Kassam said, adding that the committee had all the information it needed to make a decision in this case.

Beamish argued that the investigation of the complaint was inadequate because the college failed to obtain available evidence related to the allegations of racial stereotyping and discrimination, and did not interview the girl at the centre of the complaint.

For that girl, her mother said the trauma of the experience has been profound and has changed her relationship with her parents.

“She is all of a sudden overnight forced to grow up,” she said. “She withdrew. She doesn’t allow hugs and she used to love to hug. Now, physical touch is hard. She has anxiety where she feels like she’s not safe.”

For the girl’s father, their fight is also about holding the medical system accountable to all Indigenous people.

“My wife is fighting as hard as she can on several different layers,” he said. “So that my daughter can see that it is possible to create change.”

The family said they came forward with their story to raise funds for their legal fees and because this is a public issue about protecting Indigenous women and children when they access healthcare.

“We really need to see changes systemically in these processes. So that it is an open door for Indigenous people to come forward and share their concerns,” the girl’s mother said, “We need more and more of us to come forward and start sharing.”

They are appealing to the public through Gofundme.com in order to pay legal fees related to their HPARB review and human rights complaint.

Beamish has worked with the family since January 2020 without payment, including preparing an application and appeal for Jordan’s Principle funding to assist with the family’s costs of the complaint processes.

Both the application and appeal were rejected by Indigenous Services Canada, Beamish and the girl’s mother said.

“She can’t work for free,” said the mother. “That’s just not possible. The amount of work that’s gone into this already has been exceptional. Not only do I feel the pain of what happened to our child but I also feel the guilt of not being able to pay.”

She said the personal cost to her daughter has been very high.

“She is less comfortable with female doctors and doctors in general, but especially female doctors. She doesn’t sleep well. She doesn’t eat well. She actually developed a bit of an eating disorder after this happened.” she said.

“I don’t recognize her anymore and I hope that we’ll find her again.”