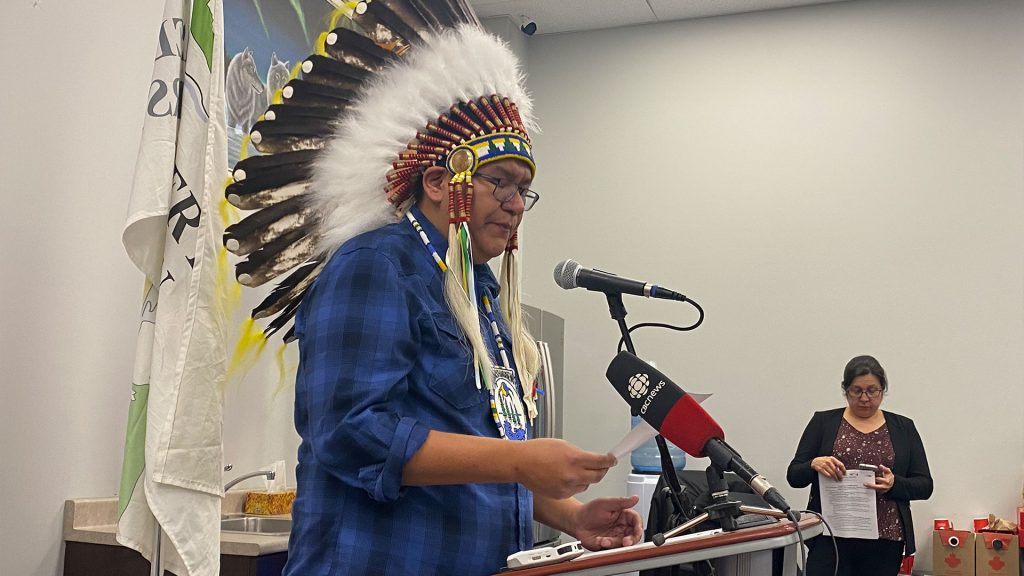

Scott Harper, is the grand chief of Anishininew Okimawin Grand Council (Island Lakes Tribal Council) in northern Manitoba. Photo: Kathleen Martens/APTN News

A remote First Nation in northern Manitoba is reeling after a student died by suicide outside his school last month.

The sudden death of the 16-year-old, whose funeral was earlier this week, prompted Chief Samuel Knott to declare a state of emergency on Oct. 20 in Red Sucker Lake.

Knott said there have been two deaths by suicide and 17 attempts in the isolated community this year. Red Sucker is a fly-in community 350 km by air northeast of Winnipeg.

“I can’t really say much,” he said in a telephone interview. “I have to be careful.”

Knott said he wanted to be cautious for fear of “copy-cats” but needed to draw attention to the crisis to get the extra services he needed.

“I’m really worried about the reactions (in the days or weeks after),” he explained.

Red Sucker, with 1,000 members, is one of four First Nations that comprise the Island Lake Anishininew Okimawin group of nations.

Together, at a news conference in Winnipeg Wednesday, all four chiefs said their band members needed treatment for mental health and substance abuse issues.

“All Island Lake community members in leadership are daily trying to help the people who are suffering so much that the risk of suicide is a constant threat,” said Scott Harper, grand chief of Anishininew Okimawin Grand Council.

“We have been negotiating with Canada for decades to fund a hospital and related facilities while our (band) members keep dying preventable deaths.”

Crisis support

Harper and other chiefs listed promises they said subsequent federal governments had made and broken when it came to delivering a regional health centre and bolstering mental health and addiction services.

They said they deserve the same health and social services as non-Indigenous communities.

“Canada must provide Island Lake first nations with substantive equality in the health and social services that other Canadians have,” Harper continued.

“An urgent strategy is needed to address colonization’s inter-generational traumatic effects, combined with decades of insufficient resources and funding, which has created a pandemic in suffering.”

The department of Indigenous Services Canada (ISC), said it had already responded to Red Sucker Lakes’ plea.

In an earlier email to APTN News, ISC said its officials met with Red Sucker Lake leaders on Oct. 21 to discuss the emergency and “offer mental health therapists.” It said a Winnipeg-based crisis team would return for a week and “prevention money” would be made available.

When asked contacted after the news conference about how it would respond to the chiefs’ appeal, spokesperson Randy Legault-Rankin agreed more needed to be done to “close the gap in access to quality healthcare between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Peoples in Canada.”

Legault-Rankin, in a second emailed statement, said the federal government supplied and staffed a nursing station in Garden Hill, Red Sucker Lake, Wasagamack and St. Theresa Point, along with air ambulance and counselling services. He said the government of Manitoba covered the salaries of fly-in doctors.

“We are deeply troubled by health and mental health concerns raised by the Island Lake First Nations,” he said in the statement. “Indigenous Services Canada (ISC) will continue to work with leadership and partners to provide them with the supports needed.”

Help needed

Knott said, while appreciated, the department’s help needed to be year-round. He also said consistent funding for land-based programs to improve wellness and harm reduction would go a long way.

“When I have a youth tell me he’s ready for treatment…he has to wait. Sometimes for months,” Knott said, noting patients are usually flown south to Winnipeg. “When he’s ready to go that day.”

Right now, a new arena in Red Sucker Lake is only half finished and there is no youth centre.

Grand chiefs Garrison Settee and Cathy Merrick from the Indigenous advocacy organizations Manitoba Keewatinowi Okimakanak and Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs, respectively, attended the news conference to offer support.

“I can relate to what the other chiefs are saying,” said Garden Hill First Nation Chief Charles Knott, whose community has 3,000 members.

“I’m just going to echo what they’re saying. Our youth need help in our communities. They’re suffering.”

Knott said alcohol and drugs had become a powerful scourge his community that needed outside medical and policing intervention.

“A couple of years ago it wasn’t like that. But nowadays these new drugs that are coming into our community – it’s taking over our community,” he said.

On its website, ISC said dying by suicide is a leading cause of death for young people in Canada. The risk is even higher in Indigenous communities, it said, because it is linked to the consequences of colonialism, discrimination, community disruption and loss of culture and language.

The Hope for Wellness Help Line, funded by the federal government, provides immediate, toll-free telephone and online chat-based emotional support and crisis intervention to all Indigenous peoples in Canada. The service is available 24/7 in English and French and, upon request, in Cree, Ojibwa and Inuktitut. Trained counsellors are available by phone at 1-855-242-3310 or hopeforwellness.ca