Stuffed animals and shoes surrounding the Centennial Flame on Parliament Hill in the summer. Photo: APTN.

At the closing event for the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) in 2015 in Vancouver, I listened with tears in my eyes to Commissioner Murray Sinclair speak of the lost and missing children from the Indian residential schools, at that time suspected to number at least 3,000.

In addition to the heartbreaking stories of survivors, and growing up in a family where many had attended the Kamloops Indian Residential School, I was overcome by shock, disbelief, sadness, anger in hearing about the children who never came home now in excess of 6,000 across Canada.

For years since, the TRC has been calling for the federal government to release all records on the children who died and to have the churches who ran the Indian residential schools release their records – to no avail. Parliamentarians have been advocating for similar measures since 2007 when Liberal MP Gary Merasty called upon then prime minister Stephen Harper to repatriate the bodies of the missing children and for an apology.

There was an apology, but for what use is an apology when there is little change in the actions that led to it?

In 2009, the TRC’s Missing Children and Unmarked Burial Project asked for $1.5 million to undertake the work of Volume 4 of the TRC and calls to action 72-76 to redress and identify the children. The request fell on deaf ears and was denied.

This summer as Indigenous communities and Canadians reeled from the discovery of the initial 215 Indigenous children from the Kamloops Indian Residential School, there has finally been a commitment ($33.8M over three years from Crown-Indigenous Relations) to find and honour the children. However, there has not been follow through on the commitment to release records from the Indian residential schools.

The National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation (NCTR) has confirmed that all records have not been provided with school narratives and supporting documents still missing as of Oct. 19, 2021 and just a general statement by Prime Minister Trudeau that the federal government is considering a legal course of action.

Meanwhile, court cases to deny compensation ordered by the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal (CHRT) to compensate First Nations children taken into care are still ongoing and with the federal government undecided if it will file another appeal with an Oct. 29, 2021 deadline to file.

So why haven’t they done it, now that the $600 million election is over and questions remain? Why did the federal government in a court settlement from July 2015 let the Catholic Church renege on its lowly $29 million cash pledge and allow a $2 million legal buy-out of $25 million commitment to fundraise obligation to survivors? Why does the federal government continue to try to appeal key decisions of the CHRT?

Haven’t we suffered enough from pre-contact times to the genocide of the Indian residential schools and colonial policy where we lost our lands, languages, children, cultures and our families? At what point will the federal government of Canada stop its war against Indigenous people?

It is said that the best predictor of the future is the past. Based on reconciliation efforts —which up until today have been little more than lip service—it is clear that Canada will not stop its war against Indigenous people. We had the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples in 1996, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in 2015, the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women in 2019, and nothing has changed.

The day the 215 Indigenous children were found at the Kamloops Indian Residential School, I realized that Canada cannot investigate itself for the continued violation of basic human rights against Indigenous Peoples in Canada that continues today. It is a blatant conflict of interest.

Through the work of Cindy Blackstock, we know that there are more Indigenous children in care today than there ever were in the Indian residential schools era, yet Bill C-92 was passed without adequate funds for implementation for all Indigenous nations to take over jurisdiction of their child and family services.

Inquiries and commissions gather dust on shelves. It remains to be seen what, when, or if there will be any meaningful implementation and budget attached to the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People (UNDRIP) that received Royal Assent on June 21, 2021.

In order for Indigenous Peoples in Canada to get truth, justice, and reconciliation, another inquiry or commission will not do.

There has been a movement in civil society by both Indigenous and non-Indigenous people and lawyers to see the intervention of the United Nations through the Expert Mechanism on UNDRIP for the appointment of a guardian entity to see the legal interests of Indigenous peoples are upheld and protected (AFN Emergency Draft Resolution #01/2021).

I and many others have been engaging with Indigenous Peoples, Indigenous groups, lawyers, and educators to explore the possibility for a preliminary examination of the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court (Rome Statute) for the government and their representatives, the churches, and the RCMP who were responsible for rounding up and delivering Indigenous children to the Indian Residential Schools for crimes against humanity and genocide, and for covering up and withholding evidence for all these years. Other avenues for international oversight may be needed as the ICC came into effect in Canada in 2002 and these crimes happened starting in the early 1800’s.

When the National Inquiry for Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls released its final report in 2019, the commissioners established that Canada carried out genocide under international law. The use of the national inquiry’s reference to genocide was questioned and in some cases denied. The federal government did not issue a response for over two years. Canada has signed on to both the ICC’s Rome Statue in 2000 adopting the Crimes Against Humanity and War Crimes Act and the 1948 Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide.

The definition according to the UN is “…acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethical, racial or religious group, as such: killing members of the group; causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group; deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part 1; imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group [and] forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.”

By the government’s own statistics, crimes and systemic racism against Indigenous Peoples and in particular against women and children are egregious. The Department of Justice in JustFacts: Victimization of Indigenous Women and Girls (2017) found that Indigenous women were sexually assaulted three times as often as non-Indigenous women in Canada; physical and sexual abuse of Indigenous young people 14 and under was 40 per cent compared to 29 per cent of non-Indigenous counterparts.

Young Indigenous women are five times more likely than other Canadian women of the same age to die of violence (Amnesty International, 2014). Canada has allowed systemic racism and genocide to run rampant in this country with no serious commitment to end these human rights infringements, and Indigenous nations are left with no choice but to appeal to international bodies. The federal government has shown since confederation its apathy towards just remedies.

Aside from calls for an inquiry and international oversight, there have also been calls to establish a National Indigenous and Human Rights Ombudsperson and a Human Rights Tribunal with the ombudsperson and tribunal being independent of governments. But again, Canada cannot be held responsible for policing and regulating itself as we have seen with the appeal of the CHRT ruling in a blatant attempt to delay and deny responsibility.

When the time comes, I’m appealing to all of our nations and Canadians to say no to an inquiry and yes to international oversight so we can begin a process of truth, justice, reconciliation, and healing for Indigenous Peoples.

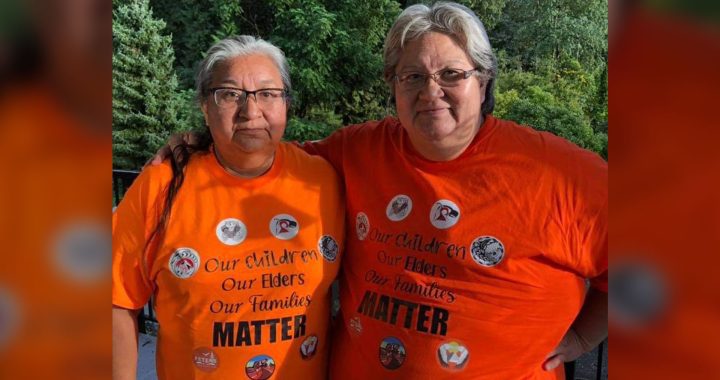

Cheryl Matthew (Simpcw First Nation) Cheryl is the executive director of Protect Our Indigenous Sisters Society and works with First Nations on land and territorial stewardship. She spent 12 years as a manager and senior policy analyst with the federal government with Service Canada and Indigenous Services Canada and has a PhD (Carleton), MA (Royal Roads), and a BA (SFU). She is an accomplished not-for-profit executive, public servant, consultant, a sometimes gardener, but most importantly she is a single working Mom.