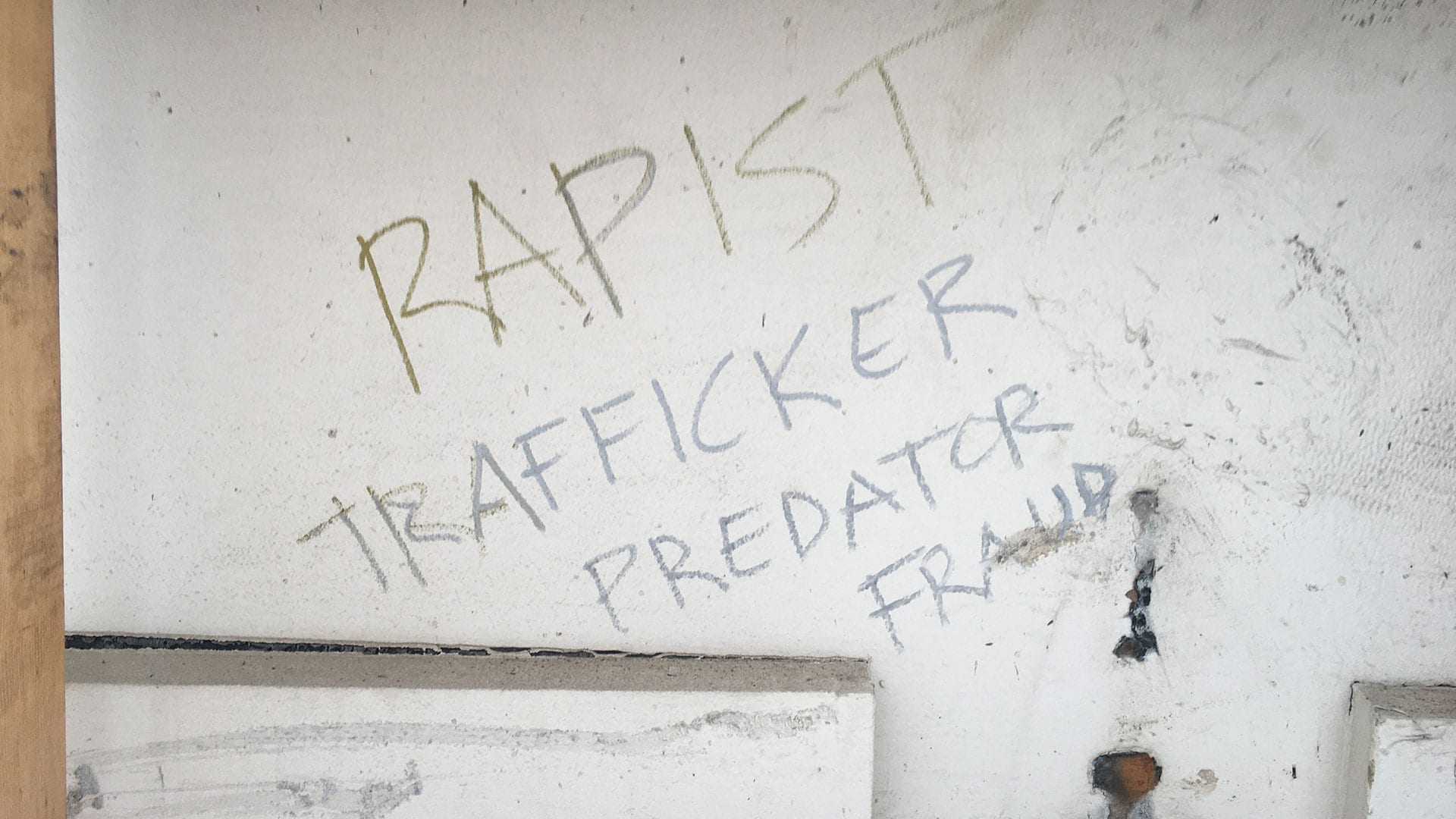

Nygard warehouse and store at 1300 Notre Dame Ave. in Winnipeg. Kathleen Martens photo

She said he told her she could be a model after their first sex act ended.

“He gave me his business card,” the woman known as Jane Doe No. 44 in a class-action lawsuit said in an interview.

“He wanted me to come to California.”

The First Nations woman, now 49, claims to have had two paid, sexual encounters with Peter Nygard, founder of the Nygard fashion empire, when she was 14 years old.

But she said she no longer has the business card.

She was a foster child living in Winnipeg – more than four hours from her Manitoba First Nation – and selling herself for spending money.

“I believe [to buy] something to eat,” she told APTN News she did with the $30U.S. she claims Nygard paid her for oral sex.

“And [I bought] weed.”

Jane Doe No. 44 is part of Jane Does Nos. 1-57 v. Peter J. Nygard, et.al – a class-action lawsuit that accuses the Canadian businessman of sexual abuse. So far 57 women – 30 from Canada – are seeking unspecified damages for assaults they allege go back four decades.

Nygard, now 79, is in custody in a Manitoba jail after being arrested in late 2020 on a warrant to extradite him to New York on criminal charges of rape, sex trafficking and racketeering conspiracy. Several of his companies, which include the Alia and Bianca clothing brands, now have creditor protection.

The mogul’s lawyer, Jay Prober of Winnipeg, calls the accusations completely false. The allegations have not been tested in court.

Jane Doe No. 44, who asked that her real name not be published, is one of two Indigenous women from Manitoba who have spoken to APTN about their involvement in the lawsuit.

“The lawsuit alleges that Defendants engaged in a pattern and practice of luring and coercing vulnerable underaged girls and women into commercial sex acts – in exchange for money, promises of modeling opportunities, promises of career advancement, and/or continued employment – through the use of alcohol, drugs, force, fraud, and/or other forms of coercion,” the class action said.

However, it is on hold pending the criminal investigation by U.S. authorities that spans at least four countries – Canada, America, the United Kingdom and the Bahamas – and alleges sexual abuse dating back to the 1970s.

Jane Doe No. 44 said Nygard was alone when he picked her up in his “black luxury car” – a Jaguar sedan, she believes. She said she was standing on Sutherland Avenue known then in Winnipeg as “the low- or kiddie-track.”

READ MORE:

Indigenous women among alleged victims of accused sexual predator Peter Nygard

It was a place to pick up young girls and pay them for sex acts, she added, noting she learned about it from other kids.

“That was survival for a lot of girls and boys in [foster] care. And we didn’t get any money for clothing or even allowance or anything, really.”

Jane Doe No. 44 said she was living in a nearby foster home – one of several she said she was placed in after being taken from her mother and forced into government care at 18 months. She said she was a ward of the province until she “aged out” upon turning 18.

Her older brother was also taken from his family by a child welfare agency, she said, and spent many years drifting through life while struggling with addiction issues.

“He’s doing good now,” she noted. “He has a residence.”

She said she told her mother about the modelling idea and her mother snapped some photos of her teenaged daughter just in case.

“Yes, I was always in contact with my mother,” she added. “[My mother] took a lot of pictures, not really knowing it was all B.S.”

Jane Doe No. 44 said it was 1992 when Nygard picked her up and drove behind the Nygard company factory and warehouse at 1300 Notre Dame Ave., in the city’s Weston neighbourhood.

The building is up for sale now and its showroom empty. Graffiti is spray painted on parts of the siding and some outdoor advertising.

A court order is in effect to liquidate assets owned by some Nygard companies – a chain of fashion stores and women’s clothing supplied to retailers in Canada and the U.S. – since the criminal indictment was laid.

The class-action alleged Nygard “promised Jane Doe No. 44” a trip, parties and alcohol.

“Nygard lured and enticed Jane Doe No. 44 by telling her the Nygard Companies could fly her to California so that she could attend lavish modeling parties,” the lawsuit said.

“Nygard paid Jane Doe No. 44 for sex acts with funds from the Nygard Companies.”

Prober, Nygard’s lawyer, didn’t respond to requests for comment from APTN left via voicemail and email. But noted Nygard has no criminal record and did not engage in inappropriate conduct.

“The ‘pamper’ parties allegation absolutely denied,” Prober recently told a Winnipeg judge hearing a bail application for Nygard.

“Illegal drugs were prohibited, alcoholic drinks were not to be strong, no underage girls there.”

Jane Doe No. 44 claimed she met Nygard a second time – months later that same year.

“Nygard drove Jane Doe No. 44 to the Nygard Companies property in Winnipeg on several occasions and paid her for oral sex,” the lawsuit alleged.

“Nygard would then drive Jane Doe No. 44 back to where he picked her up.”

Again, she said he was alone in a vehicle she thinks was a Jaguar. She said she was unaware of what he did for a living, “but I knew to have a car like that he [had to have] money.”

“We drove back to the warehouse (on Notre Dame) and we went inside,” she said.

Other plaintiffs in the 270-page lawsuit allege Nygard took them into the same building and describe “an apartment” with “a bed.”

Afterwards, Jane Doe No. 44 said he paid her with American money and they didn’t speak in the car.

“Not really,” she added. “I was very shy and not talkative.”

But now, as an adult and a mother, she said she has found her voice.

Jane Doe No. 44 has a family of her own that she said is starting to learn about “the horrors” of her time in foster care and encounters with an accused sexual predator.

She said she alternates between feeling strong and feeling despair.

“I’m getting the bigger picture of what I am a survivor of and it [is] petrifying,” she told APTN.

Nygard is not the only high-profile man to abuse her, she alleged, noting she will tell more of her story when the time comes.

She is also coming to terms with the trauma inflicted by the child welfare system that she said forced her into sex trafficking and separated her from her mother, culture and community.

“It should be more like foster kid straight to the street,” she said of what she survived.

“And I would like to encourage [others] – if there are any more survivors – to talk to police. And [to tell them] that they are not alone.”

Counselling with a therapist provided as part of the class-action and reconnecting with an Elder and other knowledge-keepers in her culture is helping her, she added.

“I was on the run and, like most young girls at that time, a lot of girls ended up on [the] kiddie-track.”

That reality haunts her, as does the number of girls she said went missing or wound up dead.

“I could probably go through all the pictures and point [out] every single girl I knew,” she added.

“You wouldn’t believe the amount of girls of my peers who are not here anymore.”

Former foster children, Indigenous organizations and advocates have linked the child welfare system to crime, exploitation and even death. They say the system is racist and apprehends a disproportionate number of Indigenous children in Manitoba.

“I was purposely pregnant by 16 hoping I was going to save myself from being trafficked any further,” said Jane Doe No. 44, noting she is speaking out not only for herself but for the foster children she said didn’t make it.

“And please do not make me look too pitiful,” she added. “I am very strong; my name is Tatanka Ska Win, which is White Buffalo Calf Woman” – a sacred woman of supernatural origin.

If you need help or know someone who does call Klinic’s Human Trafficking Hotline at 1-844-333-2211. If someone is in immediate danger call 911 or your local emergency police number.