The contents of this story may be triggering to some readers. 1-844-413-6649 is a national, toll-free support line available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.

It was 2015 when the Liberal party promised a national public inquiry into the issue of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls (MMIWG) in Canada.

As part of its election campaign, the party called the disappearance and death of an estimated 1,200 Indigenous women and girls “an ongoing national tragedy that must come to an end.”

It set the bar high – claiming the inquiry would “seek recommendations on concrete actions that governments, law enforcement, and others can take to solve these crimes and prevent future ones.”

But that lofty target was watered down in the inquiry’s official mandate, says former MKO chief Sheila North.

“It hasn’t solved anything. Neither have police,” she said in an interview.

“It set up a lot of false hope.”

Danielle Ewenin from Kawacatoose First Nation in Saskatchewan won’t even try to hide her anger at the inquiry.

“It was a complete failure,” she said. “So much for finding the truth and honoring the truth.”

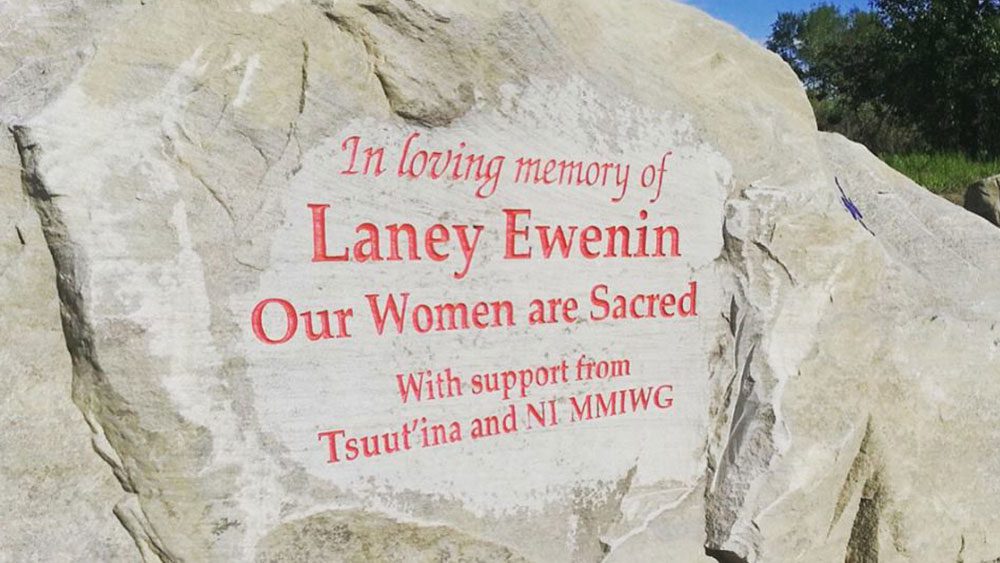

(A sandstone bench on Tsuut’ina Nation in Alberta. Submitted photo)

Ewenin’s sister, Eleanor (Laney) Ewenin, was found dead outside Calgary in 1982, when she was 23. The case remains unsolved and Danielle feels it should have been included in the inquiry’s forensic police audit.

But it wasn’t because she said the inquiry was unable to obtain the coroner and police reports she said her family asked them to find in 2016.

“If they did not have (that) there was no point (in us appearing),” said Danielle.“Nor would the (inquiry) be allowed to appear like they provided our family with a service.”

Her family had travelled to Saskatoon from their Cree community.

In January 2019, the Family Information Liaison Unit – established to work alongside the inquiry – learned the files had been stored under an incorrect name (Eleanor Cyr) and sent them to the family.

“They had $90 million and they couldn’t even do that for us,” said Danielle. “Why would I believe anything they have to say?”

(The inquiry suffered from high turnover and at times seemed to be in disarray. This image of the inquiry office in Winnipeg taken by APTN shows an empty, unorganized space. Photo: Kathleen Martens/APTN)

Willie Starr’s family had a similarly emotional experience the night before testifying in Winnipeg about his still-missing sister Jennifer Catcheway. His parents were told they’d have a short window to relay the worst experience of their lives due to scheduling issues.

They held a tense news conference at the inquiry’s hotel after contacting media outlets the night before, which led to them receiving more time.

But Starr has put that behind him. He said the big picture – the final report – will give families like his the vindication they need.

“Now Canada will see this is real,” he said in an interview before the final report was leaked last Friday. “That’s the most important thing.

“The inquiry is proof.”

(Willie Star holds a poster of his sister Jennifer at an MMIWG event. “Now Canada will see this is real,” he says of the final MMIWG. Photo courtesy: Doug Thomas)

Starr said he hopes the commissioners, who were appointed in 2016, are believed and their report respected. He doesn’t want any more turmoil.

“Families need healing, and to move forward. We need to know the country is behind us.”

Getting support for hurting families in Nunavut is why Laura Mackenzie lobbied to bring the inquiry to Rankin Inlet. It led to one of the most dramatic hearings in its mandate when Inuk musician Susan Aglukark disclosed she’d been sexually abused as a child by a male neighbour.

But it very nearly didn’t happen.

In what was becoming classic inquiry dysfunction, Mackenzie received a phone call in the weeks prior telling her the hearing was being moved to the capital of Iqaluit or perhaps Montreal.

(“There needs to be acceptance and understanding and compassion,” says Laura MacKenzie who lobbied to bring the inquiry to Rankin Inlet, Nunavut. Photo: APTN)

She contacted reporters who filed stories and the ensuing publicity put Rankin Inlet back on the schedule.

But Mackenzie, too, has filed that experience away and prefers to look to the future.

“What do I want to see in the final report? Peace,” she said.

“There needs to be acceptance and understanding and compassion now. This took a lot out of everyone, and we deserve to be heard.

“I hope this will happen. For the good of families, for the good of Nunavut, for all of Canada.”

MMIWG Inquiry concludes violence against women and girls is ‘genocide’

(Angela Lightning made the display in her yard in Carling, AB to honour missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls. Photo courtesy Angela Lightning.)

According to leaked copies of the executive summary and final report, the inquiry has concluded that persistent and deadly violence against Indigenous women and girls is a form of genocide.

The word genocide is contained throughout the 116-page executive summary of the final report sent to APTN News Friday.

Read the executive summary here: Reclaiming Power and Place

Perry Bellegarde, national chief of the Assembly of First Nations, agrees with the inquiry’s conclusion.

“(He) has said many times that the treatment of First Nations in Canada is consistent with the definition of genocide based on the many assaults on First Nations people and cultures,” a spokesman for Bellegarde said Friday.

“The violence and homicide against Indigenous women and girls is part of this pattern and governments need to work urgently with Indigenous people to stop it.”

The four government-appointed commissioners who helmed the inquiry say in the summary they agreed on the concept of genocide early on in their work, which began in September 2016.

They say they use it in their report to build on the work of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

“The truths shared in these National Inquiry hearings tell the story – or, more accurately, thousands of stories – of acts of genocide against First Nations, Inuit and Métis women, girls, and 2SLGBTQQIA (two-spirit, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, questioning, intersex and asexual) people,” they wrote.

“This violence amounts to a race-based genocide of Indigenous Peoples, including First Nations, Inuit, and Métis, which especially targets women, girls, and 2SLGBTQQIA people.

“This genocide has been empowered by colonial structures, evidenced notably by the Indian Act, the Sixties Scoop, residential schools, and breaches of human and Inuit, Métis and First Nations rights, leading directly to the current increased rates of violence, death, and suicide in Indigenous populations.”

Definition of genocide

They say they rely on this definition of genocide: “…a co-ordinated plan of different actions aiming at the destruction of essential foundations of the life of national groups, with the aim of annihilating the groups themselves.”

And, they note, Canada officially recognizes five genocides: the Holocaust, the Holodomor genocide, the Armenian genocide in 1915, the Rwandan genocide of 1994, and the ethnic cleansing in Bosnia from 1992 to 1995.

This indicates they may ask the government to recognize a sixth genocide on Monday.

The summary blames “settler colonialist structures” and “intergenerational effects of genocide” for perpetuating and encouraging the ongoing violence.

“As many witnesses expressed, this country is at war, and Indigenous women, girls, and 2SLGBTQQIA people are under siege,” it says, noting the high crime rate against this group.

“Perpetrators of violence include Indigenous and non-Indigenous family members and partners, casual acquaintances, and serial killers.”

However, the inquiry says it was unable to learn how many Indigenous women, girls and 2SLGBTQQIA people “have been lost to the Canadian genocide to date.”

The commissioners agree: “Thousands of women’s deaths or disappearances have likely gone unrecorded over the decades, and many families likely did not feel ready or safe to share with the National Inquiry before our timelines required us to close registration.

“Without a doubt there are many more.”

The summary says more than 2,380 people participated in the inquiry. And, to a person, it says their words told the pain of violence, racism and oppression.

“Colonial violence, as well as racism, sexism, homophobia, and transphobia against Indigenous women, girls, and 2SLGBTQQIA people, has become embedded in everyday life – whether this is through interpersonal forms of violence, through institutions like the health care system and the justice system, or in the laws, policies and structures of Canadian society,” it says.

“The result has been that many Indigenous people have grown up normalized to violence, while Canadian society shows an appalling apathy to addressing the issue. The National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls finds that this amounts to genocide.”

The final report is 1,200 pages.

APTN News will have full coverage of the ceremony on its website and social media platforms.