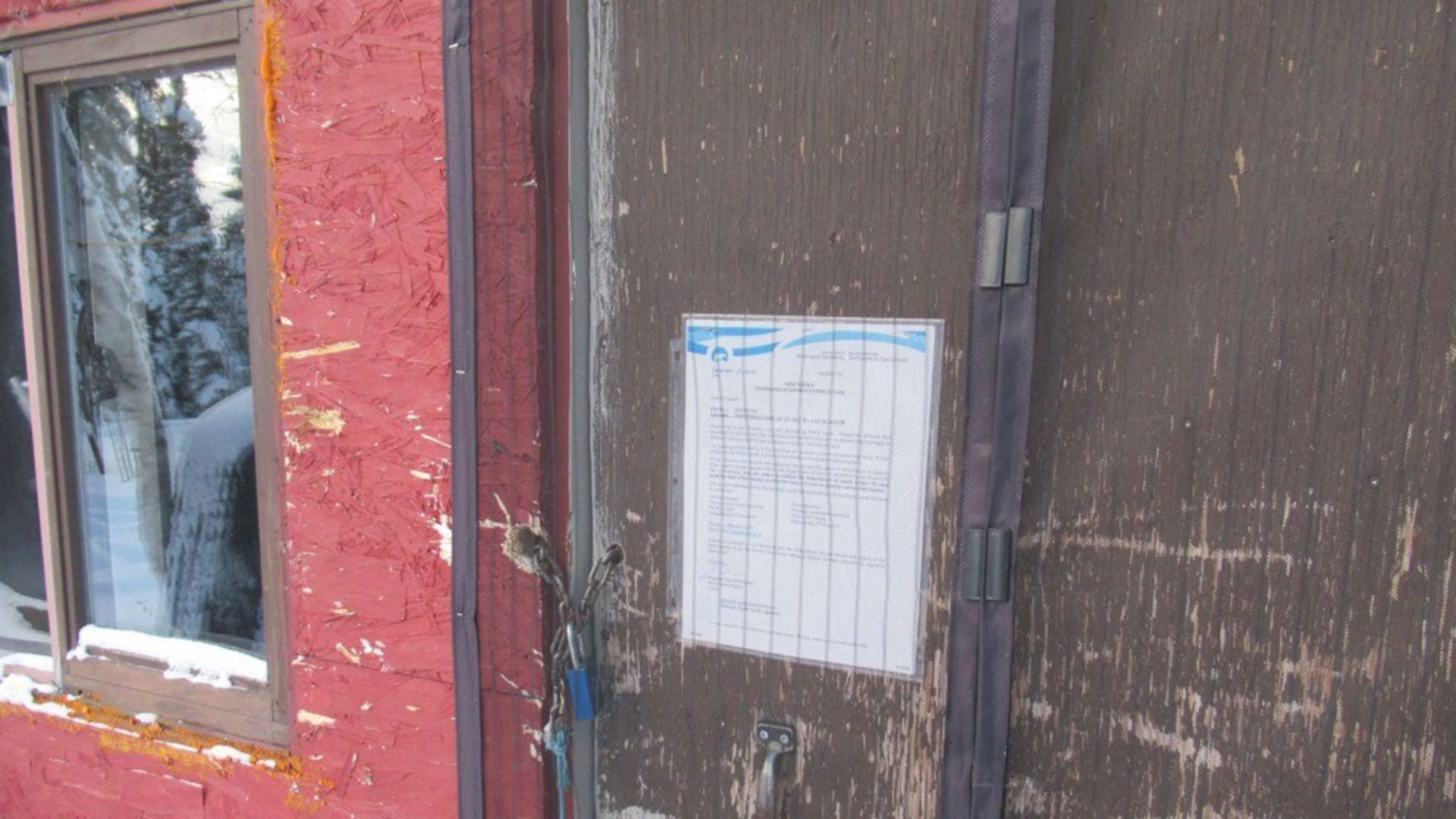

Traditional knowledge holder Fred Sangris says 100 years ago Yellowknives Dene would never have needed to post any sign stating a cabin belonged to them or that others should stay away. Photo: Charlotte Morritt-Jacobs/APTN

Fred Sangris walks the same snow-covered trail used by his ancestors for over 500 years.

The route hugs the shore of Great Slave Lake, travels through endless bush and passes areas once used as small settlements.

Sangris, a traditional knowledge holder and member of the Yellowknives Dene First Nation (YKDFN) has seen encroachment of ancestral lands for decades.

He takes APTN News to a cabin belonging to a YKDFN trapper whose cabin is now sandwiched in-between squatters,

“He [a squatter] had a lot of loose dogs barking. It drove the moose and other animals away. This guy [YKDFN trapper] is not making a living anymore he’s having a hard time,” Sangris says.

For years, YKDFN have surveyed the land and reported squatters to the territorial government who manage public lands with little progress to slow the number of cabins popping up.

But this month, the territorial government announced they would tackle the removal of illegal cabins.

“Squatting is a longstanding issue. It has been an issue for over 50 years,” said Minister of Lands Shane Thompson in a briefing with reporters. “Unauthorized occupancy has been an issue in the North for more than 50 years.

“Requiring people to get the right authorizations to use our public land is an important part of how the land is managed, but so is enforcing those requirements.”

Indigenous cabin owners who are asserting the occupancy as a rights-based cabin (a cabin residing on land where their Indigenous government/group has asserted treaty rights) will have some protection from immediate eviction.

Gina Ridgely, director of land use and sustainability for the N.W.T., told reporters the territory has worked with Indigenous governments and organizations over the last two years to identify potential rights-based cabins. But the exact number of rights–based cabins is still unknown.

“We have also created a process whereby if an Indigenous member receives a posting notice, they will have information on how to proceed with making their assertions,” she said.

An important distinction in the removal of cabins – is whether the structure was built prior to devolution, April 1, 2014 – when public lands were managed by the federal government.

After April 1, 2014, the GNWT took over responsibility of public land management.

Cabins built prior to devolution may be eligible for leases, but evaluated on a case-by-case basis, based on the department’s legislation, practices and policy.

Criteria that would allow occupants to be able to apply for a lease would include “how far a cabin is from the water and the highway system, the size of the buildings and their state, and whether or not the land is available and appropriate for leasing,” Ridgely said.

Unless it is a rights-based-cabin, structures built after April 1, 2014, occupants could be evicted.

The territorial government said they would use images from aerial photos and departmental records to determine which cabins are new and built after April 1, 2014.

Thompson noted cabin owners would be responsible for cleaning up the area they occupied.

“If someone chooses not to leave or leaves abandoned materials, we can receive authority from the courts to remove. Following removal, we can return to the courts to seek recovery of costs,” he said.

The GNWT said the project will cost more then $6 million and is expected to take the rest of the decade to complete.

While an issue across the north, Yellowknives Dene withstands the worst of the problem.

The territorial lands department estimates out of 700 unauthorized structures on public lands, roughly 550 are in the north slave region – closer to Yellowknife.

In 2020, YKDFN launched an online mapping resource and called for members to submit photos locations and comments about potential squatter camps and cabins. This campaign proved successful as the number of illegal cabins reported grew in the hundreds.

Yellowknives Dene Chief Ernest Betsina of N’Dilo said he welcomes help from the territory to address the issues but now will focus on ensuring his membership are the ones with boots on the ground.

“The GNWT has a budget so I am hoping money will flow through that to our departments; get our people out there to inspect these new buildings. All the structures that are out there,” Betsina said.

However, Betsina sees gaps in what structures will be up for eviction. The lands department told reporters that they would not immediately target wall tents occupying public lands.

“If it’s just a simple tent frame or wall tent that tent frame could be something more than just an ordinary tent frame there could be another structure after that. So for me a tent frame is the beginning of another structure they are planning,” he said.

YKDFN are also negotiating the Akaitcho land claim, which is why Chief Edward Sangris of Dettah has been asking the territorial government to stop issuing leases.

“People have to come back to the First Nations and say ‘hey I have a cabin on traditional territory, what do I do? Those are the questions that people are asking right now of us.

The lease users will have the right answer at the later date, but everyone has the mentality that it is free for now,” Sangris said.

The chief also noted that inaction to tackle the growing problem has left the First Nation to do the heavy lifting.

“There are some members from other communities that encroach, they are not YKDFN members but they are dene. It’s a as the government is saying ‘we got to kick them out’ and their First Nation advocates for them,” he said.

To get an idea of just how longstanding the issue around land management is and the confusion faced by some cabin owners, look no further than Debbora Buck-Colburn.

She began building a cabin along Ingraham trail just outside of Yellowknife in 1982 and obtained a mineral lease from the federal government on April 1, 1996.

“We’ve never hidden the fact that we were here,” Buck-Colburn said “and we’ve been paying property tax the whole time.”

She showed APTN a stack of correspondence dating back to 1984, some of the letters stating she would receive a different lease while others said she had to vacate the premises within 30 days.

“On the one hand I’m not even sure who actually has ownership of this actual area. I know it’s been all divided up and whatnot but I’m not sure if it’s the territorial government, if it’s the Akaitcho band or if it’s some other band, it’s never been clear as to which group I should be talking to about this,” she said.

For Fred Sangris, this month’s announcement did not go far enough to acknowledge the broken promises made by colonial governments to protect Indigenous lands.

He explains the history of the Yellowknife Game Preserve to APTN which was based on the map drawn by Chief Susie Drygeese in 1920s and used in the remaking of Treaty 8 in 1923.

The game preserve set aside 181,299 square kilometres (70,000 square miles) exclusive for Dene to hunt and trap on and according to Sangris was viewed by Dene as Canada’s fulfilment of the Treaty promise to protect Yellowknives Dene harvesting rights.

But prospectors who wanted to trap and harvest within the new Preserve boundaries lobbied to loosen restrictions and change the borders. Canada made a first amendment to the Preserve in 1926 and again in the 1930s discussions around the Preserve’s restriction on mining began brewing.

According the Summary of Research on the Establishment, Administration and Oversight of the Giant Mine and its Impacts on the Yellowknives Dene First Nation, a document currently being used in negotiations between Yellowknives Dene and the Federal government.

“In response to lobbying efforts from the mining interests driving Yellowknife’s growth, Canada granted non-Indigenous residents special permission to hunt within a 210-square-mile area of the reserve surrounding the settlement in the early 1940s.”

By the end of the 1940s Canada removed these areas from the settlement, and industry such as Giant Mine took its place. By 1955 the Northwest Territories Council, made up of federal bureaucrats overseeing the territories’ affairs from Ottawa abolished the Yellowknive Game Preserve entirely.

The Yellowknives Dene affirm there is no available record showing the government consulted with them on this.

Sangris sees this as important history lesson in understanding the relationship between the federal and territorial government and Yellowknives Dene.

“When GNWT took over management of land they took over management of land and trust. On behalf of the Indigenous people, the land they are managing until someday something came along like a land claim where the Indigenous people will take over that trust,” Sangris said.

The respected Elder said he is not confident in the territory’s ability to investigate their own, as some cabins may very well belong to public servants and believes his membership would benefit from a separate task force to look into the matter, managed by the First Nations.

“I think the government of the NWT needs to spruce themselves up and say ‘we need to find another regime, how we do land management’. They look at this as a frontier but it’s not a frontier it’s a homeland of Indigenous people called Denendeh,” he said.