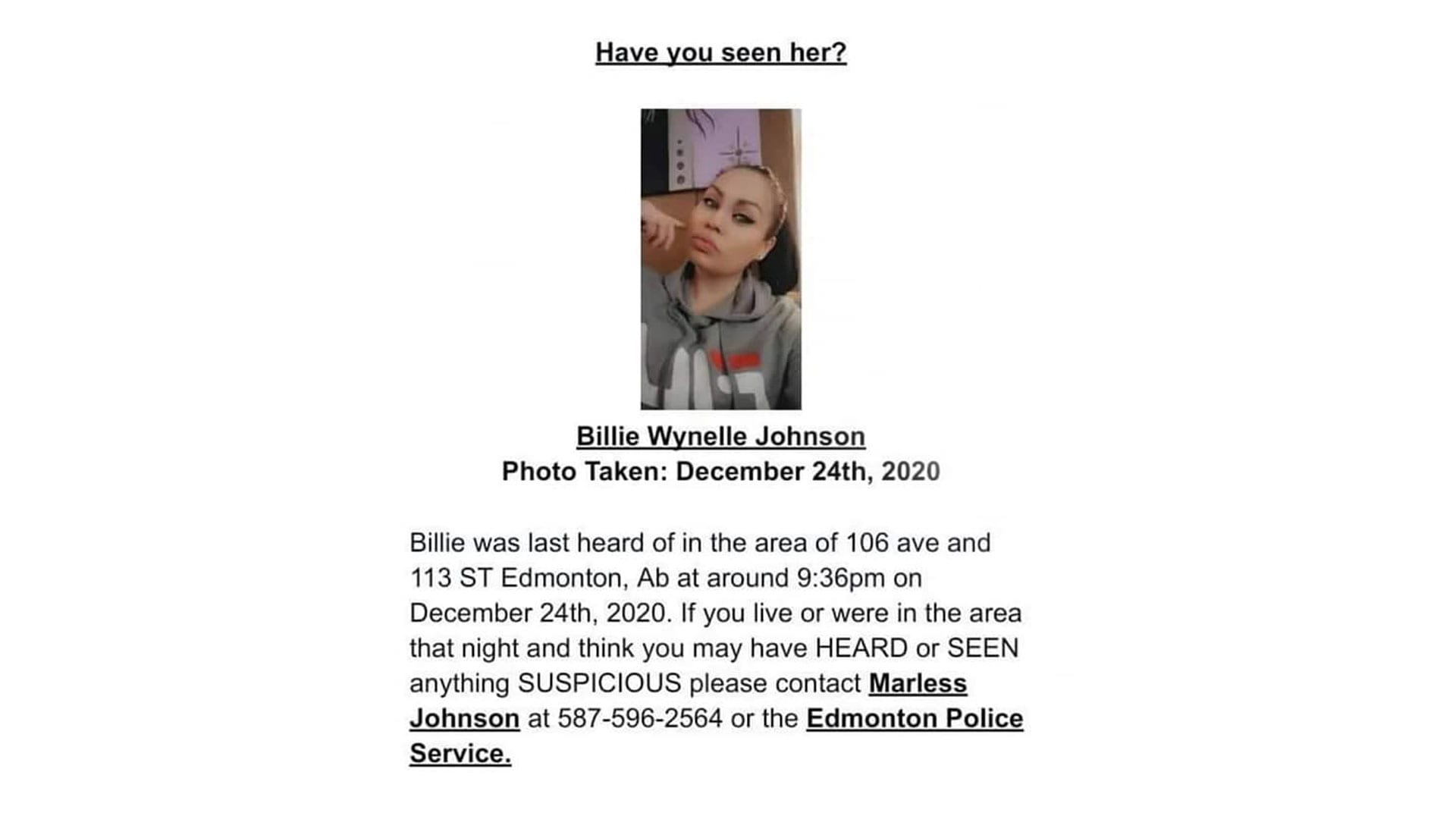

Worried sick and feeling brushed off by Edmonton police, Marless Johnson has hired a private investigator to find her daughter Billie Wynelle Johnson missing since Christmas Eve.

“They suggested she was partying,” the distraught mother said in an interview.

“They gave me the non-emergency number and that’s when those guys wouldn’t do the welfare check until morning.”

Marless is fearing the worst – that her daughter may be one of hundreds of missing and murdered Indigenous women in Canada (MMIWG) – and broke down several times while speaking with APTN News.

“I tried to get a hold of her on Christmas,” she said of Billie, 30. “And then Boxing Day. On the 27th, that’s when I got really scared.”

Marless said she reported her eldest daughter, who is a mother of two, missing on Dec. 28 after not hearing from her for four days.

“They asked me, ‘Well, what is she? Is she white, by the way? Or what is she?’ That’s what they said to me. And I said, ‘Does it matter what she is? She’s a human being.’”

APTN left messages with the Edmonton Police Service seeking more information and an interview. But did not hear back before this story was published.

Marless said Billie was living with a boyfriend who was convicted of stabbing her and is on probation. She said he told police her daughter didn’t live there when they visited his apartment.

“He had a prior conviction. She put him in jail. They were together and I didn’t know.”

Marless, who lives in Edmonton and is a member of Maskwacis First Nation, is trying everything to find Billie, including consulting an Indigenous seer in Saskatchewan.

Supporters are raising funds to hire a private investigator, and have asked Bear Clan Patrol in Edmonton to conduct a search.

“I’m leaving no stone unturned with this. I’ve had so many sleepless nights…I just want to know where she is,” Marless said before dissolving into tears.

“I can’t wait around for the police. I want my daughter found.”

Childhood friend Jamie Smallboy arranged a fundraising campaign to pay for the private investigator after spotting one of Marless’s posts on Facebook.

“She posted something early Christmas Day that she had a bad feeling and she hadn’t heard from her daughter,” Smallboy said from Vancouver.

“She talked to the cops. They told her, ‘She was not considered missing. It’s the holidays, (she is) probably partying.’ They had a shutdown for everything Marless said.”

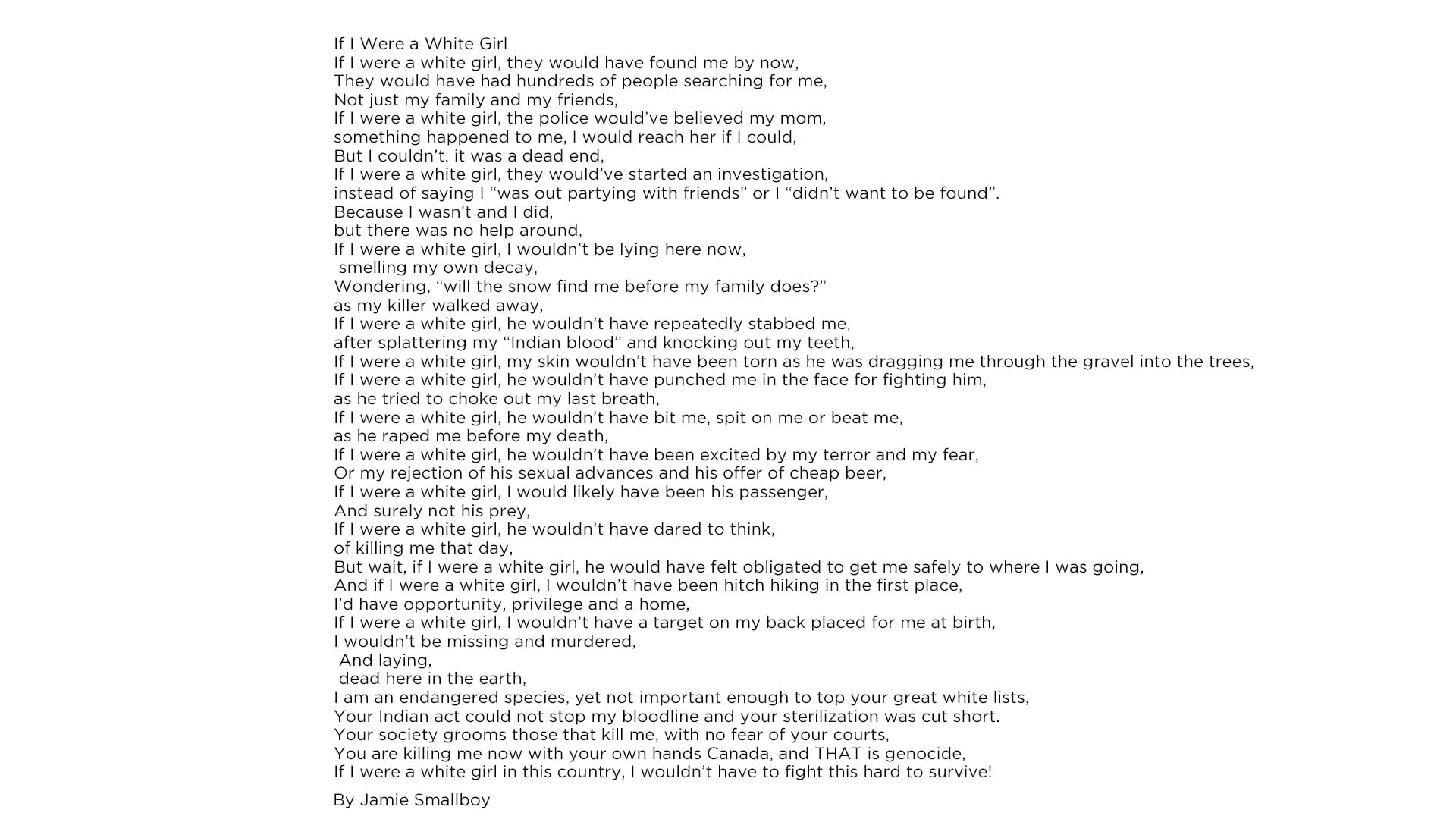

Smallboy said those racist, stereotypical responses to the parent of a missing Indigenous woman gave her rage.

“I wrote a poem about this actually a couple years ago that the cops’ favourite lines are: ‘They probably don’t want to be found. They’re probably out partying. Probably drinking. They’ll show up.’”

The way police handle MMIWG cases has long been criticized. While the number of cases is estimated at more than 4,000, the police have only solved a small number.

Their track record has generated expensive inquiries, public apologies and promises to change, noted Marion Buller, the former chief commissioner of the National Inquiry that studied Canada’s high rates of violence against Indigenous women and girls between 2016-2019.

“I wish I could say I’m surprised to hear this,” Buller said of Marless’s account.

“We heard similar stories over and over again. Real problems with communication with the police.”

Buller said police told the inquiry the first 24 to 48 hours “are critical in finding evidence, in finding witnesses, in getting surveillance camera tape” for missing persons cases.

“In one of our Calls for Justice (9.5),” she added, “we call on all police services for standardization of protocols for policies and practices to ensure that all cases of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls and two-S people are thoroughly investigated.”

Buller said many families told the inquiry they would hire private investigators if they could afford it.

“She’s still nowhere to be found,” Smallboy said of Billie. “Her phone, her social media, everything came to a complete stop Christmas Eve.”

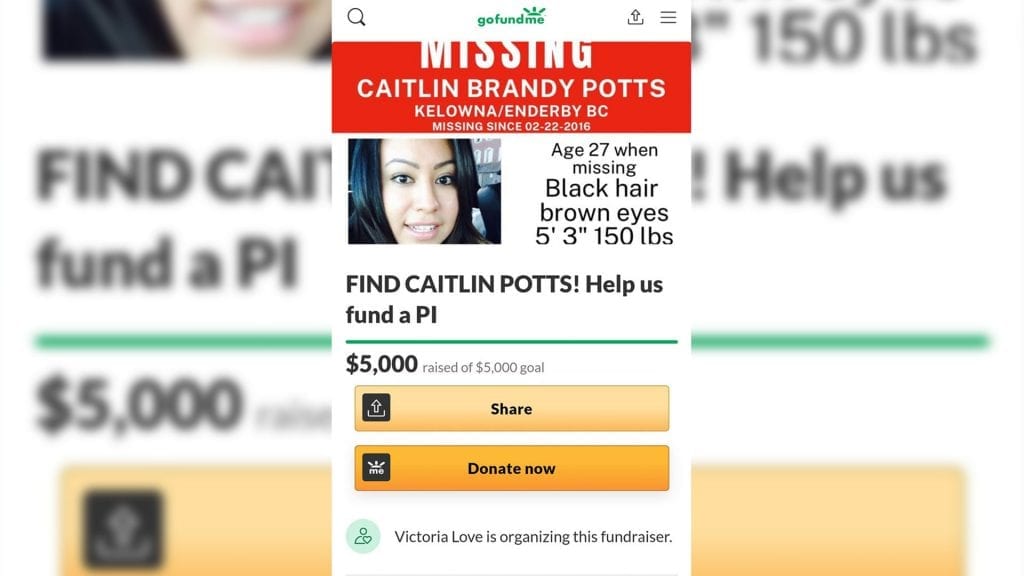

Another woman from Alberta who is missing and presumed dead is Caitlin Potts of Samson Cree First Nation.

A GoFundMe campaign, inspired by a series of TikTok videos created by an Edmonton woman, has so far raised $5,000 to help hire a private investigator.

“I don’t know Caitlin or (her mother) Priscilla (Potts),” said Victoria Love who created @storiesofthestolen. “But her friend messaged me about her, asking if I could make a video about her.”

Caitlin vanished about five years ago from Kelowna, B.C., where RCMP in nearby Vernon continue to investigate.

Love said her MMIWG videos are reaching a whole, new audience.

“It kind of just blew up; people started following me (online),” she added, noting she is now working on one on Billie.

“People told me I tell the story well. So then from there, they started messaging me asking if I could talk about their family member who is murdered or is missing, or if I could talk about their friend who is murdered or missing.”

Edmonton Police Service responded Jan. 22 to say the call between Billie’s mom and their operator was reviewed and followed industry standards. “There was no indication the evaluator asked the caller any questions that were not part of the standard repertoire,” a spokesperson said in an email.