In May 2019, APTN's Kent Driscoll took pictures of Iqaluit in the winter - when there should have been snow.

The list of how the climate crisis is affecting Indigenous communities is long — and everything on it is to the detriment of First Nations, Inuit and Métis people says a new report from Health Canada.

“The changing climate will exacerbate the health and socio-economic inequities already experienced by First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples, including respiratory, cardiovascular, water- and foodborne, chronic and infectious diseases, as well as financial hardship and food insecurity,” says the report called Health of Canadians in a Changing Climate that was released Thursday.

“Natural hazards, coupled with unpredictable and extreme weather events, can result in temporary or long-term evacuations from traditional territories, in addition to greater risk of injury and death from accidents while out on the land.”

Broken into several chapters, the report says the climate crisis will affect every aspect of life for people and “may restrict access to health systems and supplies” due to infrastructure damage or “instability,” particularly in northern and remote locations.

“Climate change threatens First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples’ ways of life, resilience, cultural cohesion, and opportunities for the transmission of Indigenous knowledge and land skills, particularly among youth,” says the report.

The report acknowledges that Indigenous peoples have been dealing with the effects of climate change for some time – but that this is the first government report that includes a chapter specifically dealing with the effects of the climate crisis on Indigenous Peoples.

The report says Indigenous people are “uniquely sensitive” to the impacts of the climate crisis “given their close relationships to land, waters, animals, plants, and natural resources; tendency to live in geographic areas undergoing rapid climate change, especially Northern Canada; and greater existing burden of health inequalities and related determinants of health.

“They result from direct and indirect impacts of climate change that exacerbate existing inequities, and affect food and water security, air quality, infrastructure, personal safety, mental well-being, livelihoods, and identity, as well as increase exposure to organisms causing disease.”

The report says in some areas there is an “unprecedented rate of change” and that has led some communities and organizations to declare states of emergency to help deal with the changes.

The Health Canada study is part of a larger, coordinated effort over several federal departments including Environment and Climate, Natural Resources Canada and the National Research Council to study the current and future effects of climate change on infrastructure and people across the country.

Read More:

Floods, drought and wildfires will worsen as Prairie climate warms, says federal government report

In January 2021, Natural Resources Canada issued the first in a series of reports on climate change and how it will affect Canadians. The first report explored how the Prairie provinces will be impacted.

Scientists involved in the report predicted that extreme weather events will get more severe and could present the most challenging, and expensive, consequences of climate change in Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta.

That means more intense rain generating more powerful floods. It means hotter summers, drier tinder and more destructive wildfires in a region that, within the last seven years, witnessed two of the costliest weather-related disasters in Canadian history.

“There’s good scientific evidence, now, that the severity of these events is worse because they’re occurring in a warmer climate,” said Dave Sauchyn, director of the Prairie Adaptation Research Collaborative at the University of Regina, in an interview.

“We call it the amplification – amplifying or enhancing the severity of these events. This effect will only increase as the climate gets warmer.”

In the summer of 2021, temperatures in British Columbia rose to new records as wildfires scorched thousands of hectares of forest and claimed at least one community.

Climate crisis will create ‘ecological grief’

But almost nowhere in Canada is the crisis more acutely felt than across the Arctic where some communities are noticing their surroundings changing before their eyes.

Homes in some communities in the Northwest Territories are slowly disappearing into the sea because of melting permafrost, and melting sea ice is forcing hunters to stay close to shore.

The report uses the example of Vuntut Gwwitchin First Nation (Old Crow) in the Yukon that issued a state of emergency in May of 2019 saying their traditional way of life was “under threat from the rapidly changing landscape.”

It quotes Chief Dana Tizya-Tramm saying, “It’s going to be the blink of an eye before my great-grandchild is living in a completely different territory, and if that’s not an emergency, I don’t know what is.”

The report says because some activities are limited, the crisis is causing the “loss of knowledge and land skills related to weather prediction, transportation to hunting grounds, and wildlife patterns, leading to increased risk of injuries and fatalities and reduced access to country food.”

According to the report, the number of calls for search and rescue operations has “more than doubled over the past decade due to changes in temperature and ice.”

The authors say the “loss of knowledge and skills” threatens Inuit identity and well-being by forcing Inuit to stay on land rather than venture out for “sea-based activities” and for sharing and teaching knowledge and skills to young people.

“Permafrost degradation, heavy storms, and coastal erosion can result in the destruction of places that have cultural significance, with potential mental health impacts,” the report says. “Such events can also destabilize housing, pipelines, and local civic water, wastewater, and transportation infrastructure and systems increasing the risk of injury, water-borne illnesses, and environmental contamination, as well as causing disruptions in supply chains.”

The loss of land and unpredictable weather patterns are also causing what the authors are calling “ecological grief” and expect it to become more common from “past and future climate-change-related losses of land, ecosystems and species, environmental knowledge and cultural identity.”

In response, those communities will experience “increasing mental health issues” that will be difficult and challenging to deal with considering First Nation, Inuit and Métis communities “lack adequate mental health services.”

Infectious Diseases

The change in weather including warmer temperatures, more precipitation and more frequent drought and wildfires is expected to affect the “incidence and distribution of water and foodborne diseases.”

First Nations, Inuit and Métis peoples are “at an increased risk of exposure to climate-related infectious diseases because of a strong reliance on traditional or country food.”

The authors cite recent studies that indicate an “increased prevalence of parasites in wildlife causing “trichinellosis in walrus and polar bear, brucellosis in caribou, lungworm infection in muskox, giardiasis in beaver, as well as tularemia, rabies, and cryptosporidiosis.”

According to the report, “These diseases have the potential to be transmitted from animals to humans, either directly, from the consumption of traditional foods, or indirectly, through exposure to domestic animals carrying these pathogens.

“Indigenous Peoples globally and across Canada have significantly higher rates of infectious diseases than non-Indigenous populations placing them at greater risk for climate-related infectious diseases,” says the report.

“A high prevalence of giardiasis has been detected in Northern Canada, while rates of cryptosporidiosis appear to be extremely high among Inuit in the Qikiqtani region of Nunavut and the Nunavik region of Quebec compared to the Canadian average.”

The report warns that while these gastrointestinal illnesses are generally mild and resolve themselves, “it remains a leading contributor to infant mortality among young children in the Arctic.”

Down south, the rise in temperatures is helping spread what are called vector-borne diseases such as Lyme disease and West Nile virus. These diseases are carried by mosquitos, ticks and other biting insects. Both Lyme disease and West Nile virus are “recognized as potential health risks by some First Nations.”

At the moment, these diseases are not a threat to the Arctic.

Freshwater down south and in the north

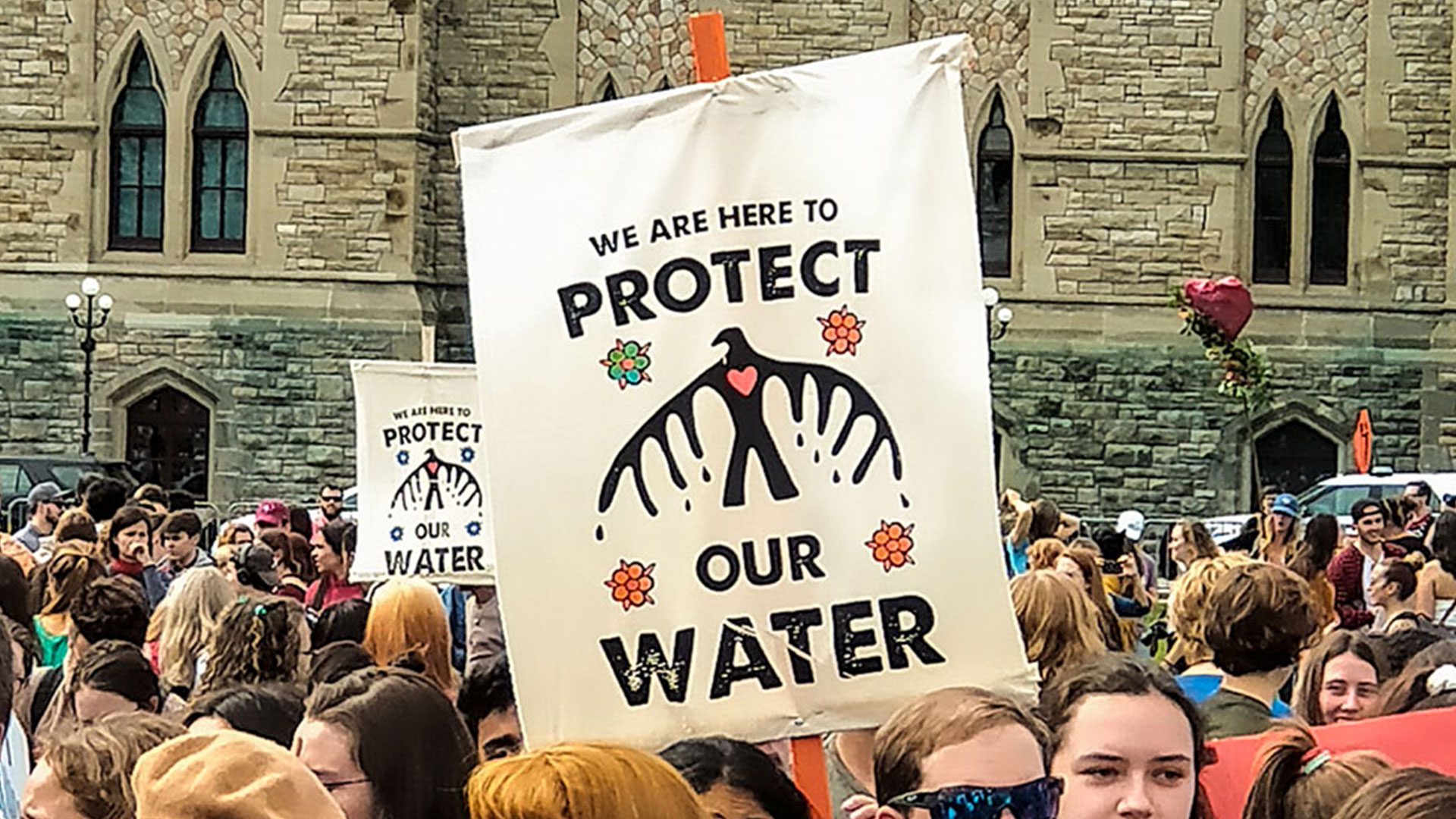

First Nations communities have been reporting climate change and water security issues long before this report was published.

According to a number of studies cited in the report, “numerous First Nations communities have reported rapid declines in water levels, with significant impacts on the availability of fish resources and the migration and movement of other animal resources that are important for food security.”

In the Arctic, the climate crisis has “increased evaporation of the freshwater supply, the contribution of groundwater to river flows, and permafrost degradation,” the report says.

These impacts, the report says, will only put more pressure on existing water systems and the availability of drinking water.

Canada’s international commitments and the climate crisis

The government report acknowledges that “First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples have been actively observing and adapting to changing environments in a diversity of ways since time immemorial.”

It also acknowledges that “Indigenous knowledge systems and practices are equal to scientific knowledge and have been, and continue to be, critical to Indigenous Peoples’ survival and resilience.”

“First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples are rights holders. Preparing for the health impacts of climate change requires that Indigenous Peoples’ rights and responsibilities over their lands, natural resources, and ways of life are respected, protected, and advanced through distinctions-based, Indigenous-led, climate change adaptation, policy, and research,” it says.

The report also warns that Canada, under international law, is compelled to protect the rights of First Nations, Inuit and Métis.

The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) recognizes the urgent “need to respect and promote the inherent rights of Indigenous Peoples which derive from their political, economic and social structures and from their cultures, spiritual traditions, histories and philosophies, especially their rights to their lands, territories and resources.”

And it recognizes that Indigenous Peoples have “the right to the conservation and protection of the environment and the productive capacity of their lands or territories and resources”

Under the federal government’s program to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, the Assembly of First Nation, Métis National Council and Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami are working with Canada to develop a plan to ensure that Indigenous Peoples are leaders in the fight against climate change, advise on regulations and share monitoring information.

As well as working with the AFN, MNC and ITK, at the national level, “grassroots Indigenous-led organizations, such as Indigenous Climate Action, are also playing an important role in climate change in Canada by pushing for the incorporation of Indigenous rights and knowledge in climate change discussions and solutions.”

Do you have a story about how the landscape or climate is changing in your community? Write to us: [email protected]