Helena Wood with her daughters at the feast for Cassandra. Submitted photo.

Warning: This story contains details that some people may find disturbing. The Canada Suicide Prevention Service enables callers anywhere in Canada to access crisis support using the technology of their choice (phone, text or chat), in French or English: Phone: toll-free 1-833-456-4566 Text: 45645

On almost a regular basis, Cassandra Wood witnessed her father attack her mother in the family home on St. Theresa Point First Nation in northern Manitoba. The violence went on for years.

Eventually it became too much – at the age of 15, she died by suicide.

This past February marked the 10-year anniversary of her death and to commemorate the day, the teen’s family traveled home to hold a feast and visit the site where she was found.

This was the first time the family was able to do this together since Cassandra died Feb. 26, 2010.

“It was closure for us,” Cassandra’s mother Helena Wood told APTN News. “We talked about her and went to see the site.”

After witnessing years of domestic violence, Cassandra sought support that Wood says never came.

Island Lake Family Services first intervened in December 2008 when Cassandra told a local health worker she didn’t want to go home because of the violence.

Wood says over the next 15 months leading up to the teen’s death she never spoke with a therapist because the isolated community did not have a dedicated counsellor.

“There’s always a waiting thing. A waiting list for a doctor, a waiting list for a therapist,” said Wood.

“We just need more therapists out there.”

Cassandra is one of many children and youth who have died in the province from 2009 to 2019.

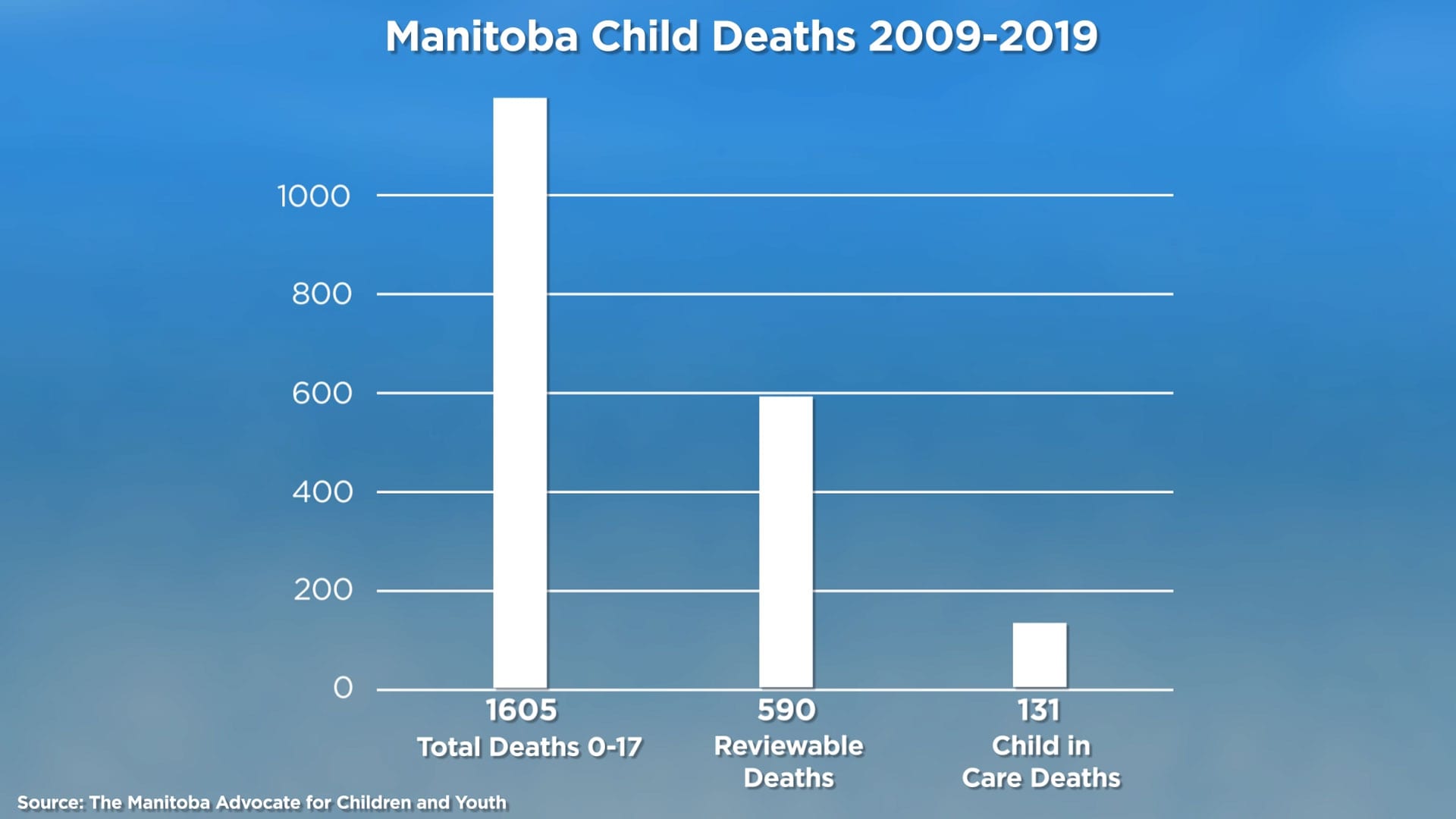

According to statistics from Manitoba Advocate for Children and Youth Daphne Penrose’s office, there have been 1,605 deaths in the last decade of youths ages 0 to 17.

Of those, 590 are what Penrose calls “reviewable deaths” meaning the person had some contact with the child welfare system within the past year of their life.

In total, 131 were classified as in government care at the time of their deaths.

According to Penrose, death by suicide continues to be the leading cause of mortality for youth in Manitoba, so much so, it was the subject of an aggregate report she released in May.

Read More: New report showcases gaps and barriers in youth mental health services in Manitoba

Penrose has repeatedly called for easier access to mental health resources, especially in First Nations.

“Those intervention and prevention services in the beginning are so critical to families so that they can have better outcomes and that Child and Family Services doesn’t need to become involved in their life,” said Penrose.

In many cases families will request support from the child welfare system to help with children or youth living with a disability, mental health issues or if they are need of respite care. This is often done because the family cannot access resources through other means or they are not available in the community.

In previous reports, Penrose has called for the provincial government to prioritize resources in rural and remote locations, as well the resources must be, “culturally-informed, and be developed in ways that reflect the voices and preferences of Indigenous health experts, Indigenous leadership, children and youth.”

“Have communities decide about what resources they need so that they can provide meaningful help to their kids,” Penrose said to APTN.

In Manitoba, there are 10,000 to 11,000 of kids in care in any given year with 90 per cent of them being Indigenous.

Penrose’s office does not keep track of how many of the deaths are Indigenous children or youth citing they are notified by the coroner’s office but are only sometimes given a name and little else.

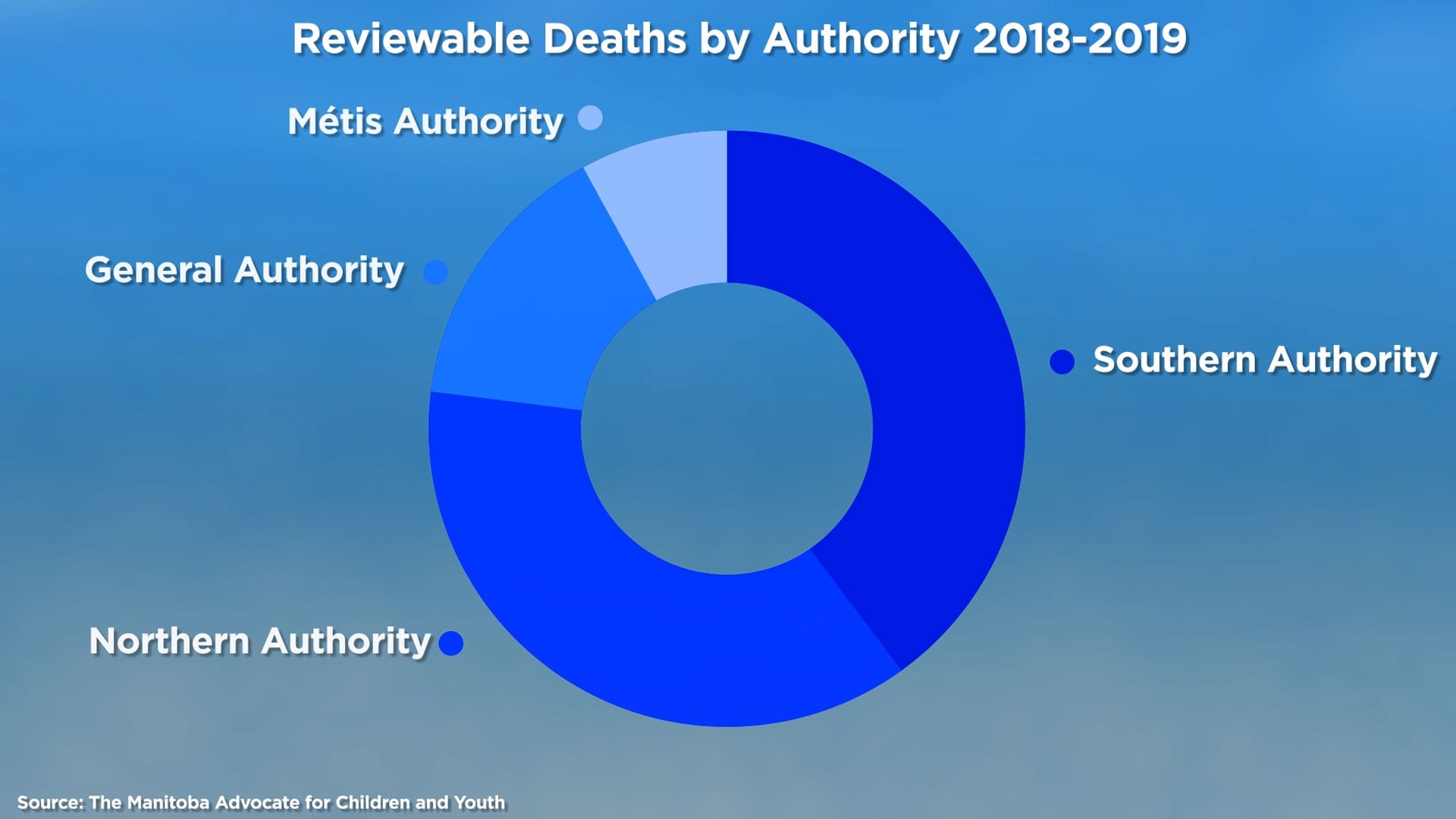

However, statistics from the advocate’s annual report shows there were 70 reviewable deaths for 2018 to 2019 and Indigenous people accounted for at least 85 per cent of those.

Of those, just under half were part of the authority consisting of several southern First Nations.

Southern Chiefs’ Organization Grand Chief Jerry Daniels equates these high numbers to poverty levels in communities and from there it trickles into other aspects of peoples’ lives.

“The compounded issues are the addictions that we’re seeing now… drugs creeping into our communities. The inability of our peoples to find a way out of that addiction,” said Daniels.

Daniels says the child welfare system alone cannot address years of systemic racism that have lead to the high number of Indigenous youth in care adding it takes collaboration among government institutions.

“Every child from the moment they’re born should have a support system in place that evolves and is dynamic and changes but is all about supporting the child.”

In Ontario, the number of youth who have died while receiving care is typically and quietly posted on the coroner’s website every year. However, the province just recently provided APTN data for the last two years after refusing for months. From 2013 to today 172 children died with society involvement in the province. Since the pandemic hit in March, 11 Indigenous kids connected to the child welfare system died.

Read More: 11 Indigenous children died in last four months connected to Ontario’s child welfare system

Former Ontario children’s advocate Irwin Elman calls the numbers unacceptable.

“These are the children who the state has intervened to protect them so at a minimum the government needs to say something is not right,” Elman told APTN.

“Our children must survive our attempts to protect them. How about that for an outcome.”

The NDP in Ontario have called for an emergency investigation into the deaths there.

Advocates have been expressing concerns over access to resources during the pandemic, especially for youth exiting the child welfare system.

Ontario and Manitoba are among some of the provinces who have committed to extending supports for youth who are supposed to “age out” during the pandemic meaning once they become legal they can still access services.

Conner Lowes is the Ontario director for Youth in Care Canada, a national youth advocacy organization, and says the pandemic has heightened concerns for youth in care.

“There’s food insecurity, there’s familial insecurity, social isolation, there’s homelessness,” said Lowes.

Youth in Care Canada along with Ontario Children’s Advancement Coalition have created a proposal to create a readiness-based system for young people leaving care in Ontario. This would mean instead of the province relying on an age indicator system they would develop a system where youth would leave care when they have the proper resources put in place.

“When you use those measurements for whether or not a youth is ready to leave it means they get to leave on their own terms and they don’t have to be kicked out before they’re ready because that’s setting them up for failure,” said Lowes.

In Manitoba, the advocate’s office says the number of deaths in the first quarter of 2020 is consistent with the number of deaths during the same period last year.

There have also been demands to defund the child welfare system similar to calls to defund police agencies across the country.

Penrose believes there needs to be a shift in traditional child welfare practices.

“I think it has to do with changing how services are delivered. Making sure that the people who are delivering them understand how to help the families and how to work with families as the experts,” she said.

The Canada Suicide Prevention Service enables callers anywhere in Canada to access crisis support using the technology of their choice (phone, text or chat), in French or English: Phone: toll-free 1-833-456-4566 Text: 45645

With files from Kenneth Jackson