Haíɫzaqv (Heiltsuk) Granny Gardeners growing gifts from Haida Gwaii. Photo courtesy: Jess Housty.

On Sept. 10, Jess Housty whose traditional name is ‘Cúagilákv, took to Twitter and wrote: “Our Haíɫzaqv Emergency Operations Centre has confirmed the first positive case(s) of COVID-19 in our community.”

Housty is the executive director of Qqs (Eyes) Projects Society, (QPS), a Haíɫzaqv (Heiltsuk) charitable non-profit focused on supporting youth and families to thrive through community and cultural programming.

As the first positive case of COVID-19 has now been confirmed in her community, Housty is thinking about how they can take care of each-other.

She says a big part of how she will do that is through gardening.

“There’s so little I can control in the context of a global pandemic knocking at our door, but I can control my garden and the abundance I have to share,” says Housty.

“This morning I went and did a big veggie pull from the community garden to drop off at Elders’ doors.”

Our Haíɫzaqv Emergency Operations Centre has confirmed the first positive case(s) of COVID-19 in our community. Let’s all be our best Haíɫzaqv selves — be kind, take care of ourselves and one another, and look out for our elders. Please abide by the HEOC’s precautionary measures.

— Jess Housty (@jesshousty) September 10, 2020

In her role with QPS, Housty has been teaching gardening classes throughout the pandemic.

“The early part of the pandemic was a wake-up call about the importance of being self-reliant in case COVID or other crises caused significant disruption,” she says.

“Knowing that the coming weeks are uncertain and that our ability to quickly curb community spread will set the tone for the winter months, I’m just grateful that I’ve been filling my pantry with preserved foods our family grew — that we have fall and winter crops in the ground now — and that we’re actively saving seeds for next year.”

Why gardens

Since 2013, the community has been working to build up programs that support food sovereignty.

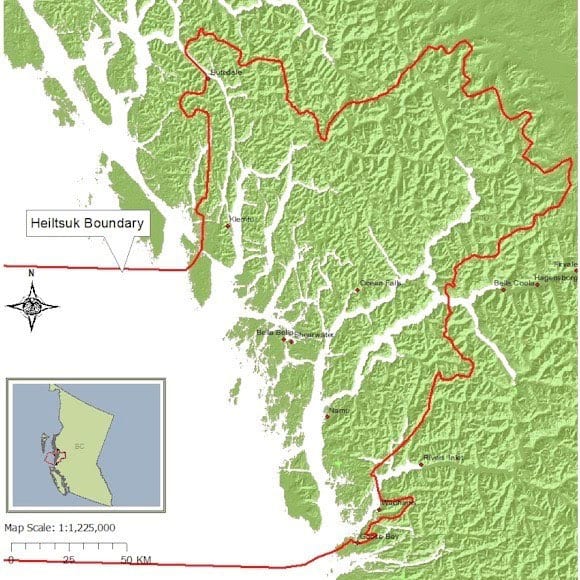

Haíɫzaqv Territory is on the outer central coast of B.C. It stretches from the edge of Vancouver Island, out through all the other coastal islands into the open ocean. Around 120 years ago, Haíɫzaqv people gathered in the village of Bella Bella.

“The few Haíɫzaqv people (around 1 per cent) who didn’t succumb to influenza and smallpox banded together here. We are the descendants of those who survived epidemics,”Housty explains.

As a geographically remote community, growing food is important, says Housty.

Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, this has become an even greater focus.

“We’ve been able to adapt a lot of what we’ve been doing to be… COVID safe and support people through the pandemic. And it’s been really beautiful and really affirming,” says Housty.

An expression of food sovereignty

Food Sovereignty is defined as “the right of peoples to healthy and culturally appropriate food produced through ecologically sound and sustainable methods, and their right to define their own food and agriculture systems.”

For the Heiltsuk Nation, this is reclaiming and strengthening the food security their people have had for thousands of years.

Housty defines food sovereignty through a holistic view.

“Food is medicine, and food is community building. In gardening, we express food sovereignty. We take responsibility for nourishing ourselves and our loved ones with good food that will make our bodies strong,” she says.

Gardening is something Haíɫzaqv people have done since time immemorial, despite common “hunter-gatherer” generalizations Housty explains.

The generalization was continued through the misconception that Indigenous people on the West Coast did not have agriculture.

“One of the things that I contend with in my food security, food sovereignty work is this notion,” says Housty, “…that all indigenous people were hunter-gatherers and that our relationship to places and resources in our territories was incidental and opportunistic. And the more I had dug into ancestral systems knowledge here, the more I realized how untrue that idea is.”

In Haíɫzaqv (Heiltsuk) Territory, there are several examples of traditional agriculture and sophisticated cultivating methods.

Springbank clover and rice lily root patches are among the plants in estuary gardens. Gardening was done by tending and fostering patches.

Similar to current permaculture practices, plants were weeded, thinned, nourished, selected and propagated. Research shows these garden patches were handed down through generations.

Clam gardens are another example of Haíɫzaqv people gardening for millennia.

These clam gardens were carefully nurtured and tended. Research shows they have existed in Haíɫzaqv territory for at least 2,000 years, and possibly thousands of years longer.

Radiocarbon dating rock walls is difficult, as scientists need to find bits of organic matter between the rocks, or barnacle scars to take dating samples from.

“Our ancestors have a really deep relationship to places and systems that they nurtured to thrive for our mutual benefit and an act of reciprocity and kinship that has nourished our people since time before memory and realizing that…has given me this truth,” Housty says.

Housty shares the profound shift when acknowledging traditional ecological knowledge.

“That’s so at odds with this idea of us as hunter-gatherers, and has totally transformed my understanding of who I am in relation to health and food systems.”

Indigenous households are experiencing food insecurity

Housty describes her home territory again, this time through a lens of food distribution, chains of supply and transportation. Food supplies including dry goods and fresh produce arrive in Bella Bella once a week, by ferry or barge.

“For geographically remote communities… by the time food supplies get here, it is not in its prime state. It travelled so far that people carry this burden of guilt from the carbon footprint of the products they’re consuming,” she says.

Some fruits and vegetables are shipped thousands of miles to Canada and then continue the journey to geographically remote communities like Bella Bella.

The transportation costs are often handed down to the consumer, who pays more in the end.

“It’s often picked when it’s under ripe in order to transport this far. When you factor in the cost of creating that product here, it’s just quickly out of reach [for] lots of people in the community, ” says Housty.

“And then just realizing that what is available to us to come in from the outside world is often too expensive for people to access or, frankly, not as very high nutritional value.”

This correlates to findings in a PROOF report released March 2020.

“Food insecurity means inadequate or unstable access to nutritious food due to financial constraints,” the report states. “More than 1 in 8 Canadians are experiencing this right now.” This is higher than any prior national estimate.

Yellowhead Institute similarly shared concerns on food insecurity for Indigenous communities.

Its report reads: “With the pandemic and emergency measures such as the restriction of movement, border closures and food hoarding, which will result in an increase in food costs and unemployment, these numbers will only get worse.”

The pandemic and emergency measures required to protect communities have impacted distribution of food supplies on a wide scale.

“We do have a fabulous grocery store here that works very hard,” explains Housty. “But they’ve been impacted by COVID… Those external supply chains feel a little more tenuous and the logistics get a lot harder, getting what we need here.”

Granny Gardens and wellness

In Haíɫzaqv territory, food systems work is clearly important during a pandemic. COVID impacted in-person workshops, and stopped larger community garden activities.

QPS grows food at a field site to feed families and kids attending their seasonal programs, and started a community garden in Bella Bella in 2016.

In a normal year, there is collaboration with the Heiltsuk Health Centre, and a team of gardeners is dispatched in the summer to support people with their home gardens. However, this group work was interrupted by COVID, while increasing food insecurity.

Supplies in hand, the focus pivoted and adapted into the Granny Gardens.

Seeds and plant starts were shared, and physical distancing and personal protective equipment were used in demonstrations.

Cheerful videos on social media were used to teach and stay connected.

In one of the videos for the Granny Gardening program, Housty holds a potato close to the camera and smiles with obvious delight.

“Look at these beautiful, deep, purple potatoes,” she says. “Our Haida relatives enrich us and nourish us in so many ways, and now there’s one more: Haida Gwaii potatoes are successfully growing here in Haíɫzaqv homelands.”

Housty says the granny gardeners were drawn to the project because of what it gave them.

“A routine in terms of safety and stability in the early days of the pandemic… to help people become more familiar with how special plant resources they may not be aware of here,” she says.

“We’re still actively using them… their families that are out there in abundance, all around us.”

Granny Gardens is a rebranding of the Victory Garden concept says Housty.

Victory Gardens were encouraged by governments during the First and Second World Wars. People planted them not only to supplement their rations but also to boost morale.

With Granny Gardens, the value of resilience is shared, but the imperialist connotation is not.

Housty explains that the granny element of the project name is honouring and recognizing the millennia of women working together, harvesting and tending gardens in Haíɫzaqv lands.

Housty shares some of the feedback she received from one of the granny gardeners, who said, “Gardening gave me peace of mind, exercise, gratitude, knowledge of plant life, and the thrill of harvesting for my household of seven during this pandemic and my own struggles. It gave me something different to look forward to.”

Feedback from the granny gardeners also presents the variety of reasons they are participating, including the health impacts with active living and mental wellness.

“I’ve had some pretty tough issues I’ve had to deal with professionally and personally,” shared a fellow granny gardener with Housty. “And in the dirt has been my medicine.”

Another shared, “Gardening during COVID-19 times kept my kids and I busy. It was so wonderful for them to see and eat the fruits of their labour.”

There’s an element of this food security work that relates to working collectively together and also trading relationships with other communities.

“Gardening impacted my life in ways I would not have imagined. The pandemic dramatically increased my anxiety that I already really suffered with,” Housty says another granny gardener told her.

“Getting outside, with my hands in the soil with simple tasks to keep me busy honestly got me through the worst of it. Someone said that when people plant gardens, it shows they have hope for the future.”

What motivates Housty?

On Oct. 13, 2016, the Nathan E. Stewart, a tug and barge, sank after a night watchman fell asleep.

It spilled 110,000 litres of diesel fuel, lubricants, heavy oils and other pollutants into Gale Pass, an important Haíɫzaqv food harvesting, village and cultural site. It was traumatic for the community.

“The root of that trauma came from seeing the bread basket of our territory being impacted by an oil spill in a place where people would eventually be harvesting dozens of marine and inter-tidal species that they rely on for sustenance, that were suddenly just gone, virtually overnight,” Housty says.

To deal with this trauma, Housty, who is a mother, writer and land-based educator, turned to gardening.

“When I think about the root of why I started gardening, it was really a coping mechanism while I was working through trauma related to the oil spill,” she says.

“It was something that gave me a sense of agency and control over my own food security. And it was therapeutic to be outside and doing that work and nourishing living things.”

The following spring, Housty was part of organizing a community garden that was planted in recognition of responders who worked through that oil spill. QPS volunteered to lead fundraising and construction efforts as a community service.

“A huge part of our motivation was to create a beautiful space to honour first responders who were still struggling with the trauma,” she says.

The community gardening project was one way to move forward.

“Growing vegetables could never replace all of those ancestral foods that had been impacted by the spill. But knowing that you could give people hard skills, that would give them a sense of control,” she says.

Now, as the impacts of the pandemic continue, Housty is staying motivated by thinking about the deep history of her people.

“When you sort of take the long view and think about how long our people have been in our territory and thriving in our territory, the things they’ve gone through…you start to see these bigger patterns emerge,” Housty says.

She wants people to realize “the amazing circumstances that we have had, the resilience to survive through, and thrive through.”

Odette Auger is Sagamok Anishnawbek and has been living on the traditional territories of the toq qaymɩxʷ (Klahoose) also known as Cortes Island, for 21 years. Her journalism experience includes writing and producing for First People’s Cultural Council project, and local coop radio cortesradio.ca. Odette’s work is supported in part with funding from the Local Journalism Initiative in partnership with The Discourse and APTN.