She’s a single professional in her 50s, raised a son who’s made his way to success on Bay Street and she fulfilled a dream of teaching children in remote northern Manitoba communities and inner cities.

So in 2006, Jennie Davies was up for a new challenge and applied to be a foster mom in Brandon, Man.

“For the most part, people who do this want to help. We aren’t bad people,” Davies said. “I’m a white middle-aged woman with a pension.

“I have privilege and want to share that with children who need it and I’m committed to these kids. To raise them right to adulthood if needed. I’m fully committed.”

That desire to help, and her background as a teacher, made her a dream come true to child welfare agencies. She was quickly approved and set up to take children.

“Honestly, it was harder for me to adopt a dog from a rescue than to foster kids. I couldn’t believe how easy it was,” said the foster mom. “In hindsight what does that tell you?”

Whatever apprehension she had about the system she was getting into, was overshadowed by her desire to be a safe haven for kids in need.

There was an average of 11,000 kids in care in Manitoba at the time. There are still between 9,000 and 10,000 in care in Manitoba today.

Over 14 years, Davies fostered 11 children including one who is now 20 and recently completed a post-secondary vocational program.

She’s almost ready to leave the nest and has been living with Davies helping provide respite care to younger children who’ve been in the home.

“I raise good kids,” Davies says with pride.

But what she experienced recently makes her question if she’ll ever do it again.

“I will forever have a broken heart over this.”

Moving targets, gaslighting, lies and broken promises

What Davies describes is similar to what many parents report in dealing with child welfare – ever-changing hoops and moving targets, gaslighting, lies and broken promises.

The beginning of the end was two years ago when Davies took on a family of five ranging in age, at the time, from two to 10 from South East Child & Family Services, the largest First Nations child welfare agency in Canada, according to its website.

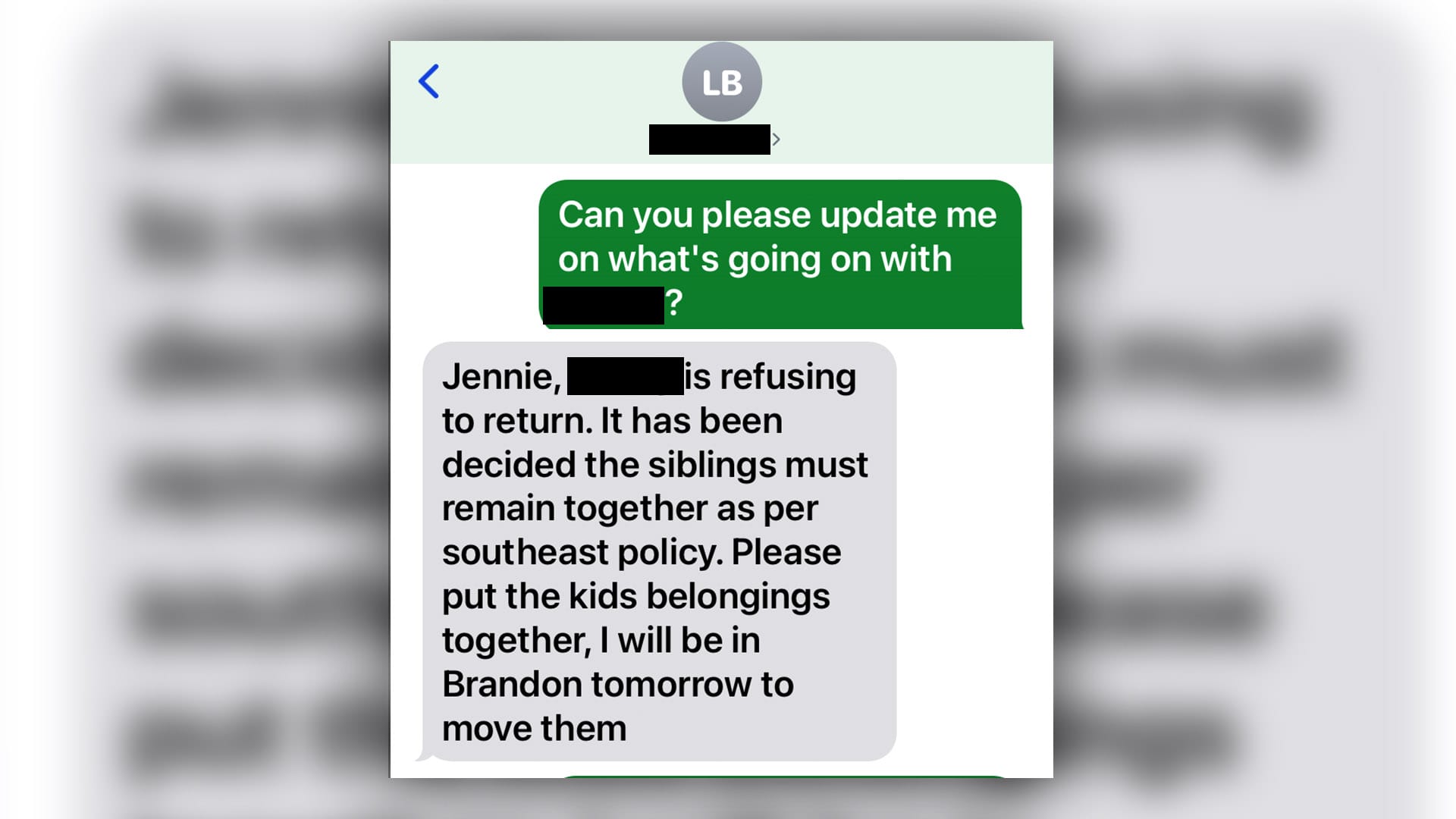

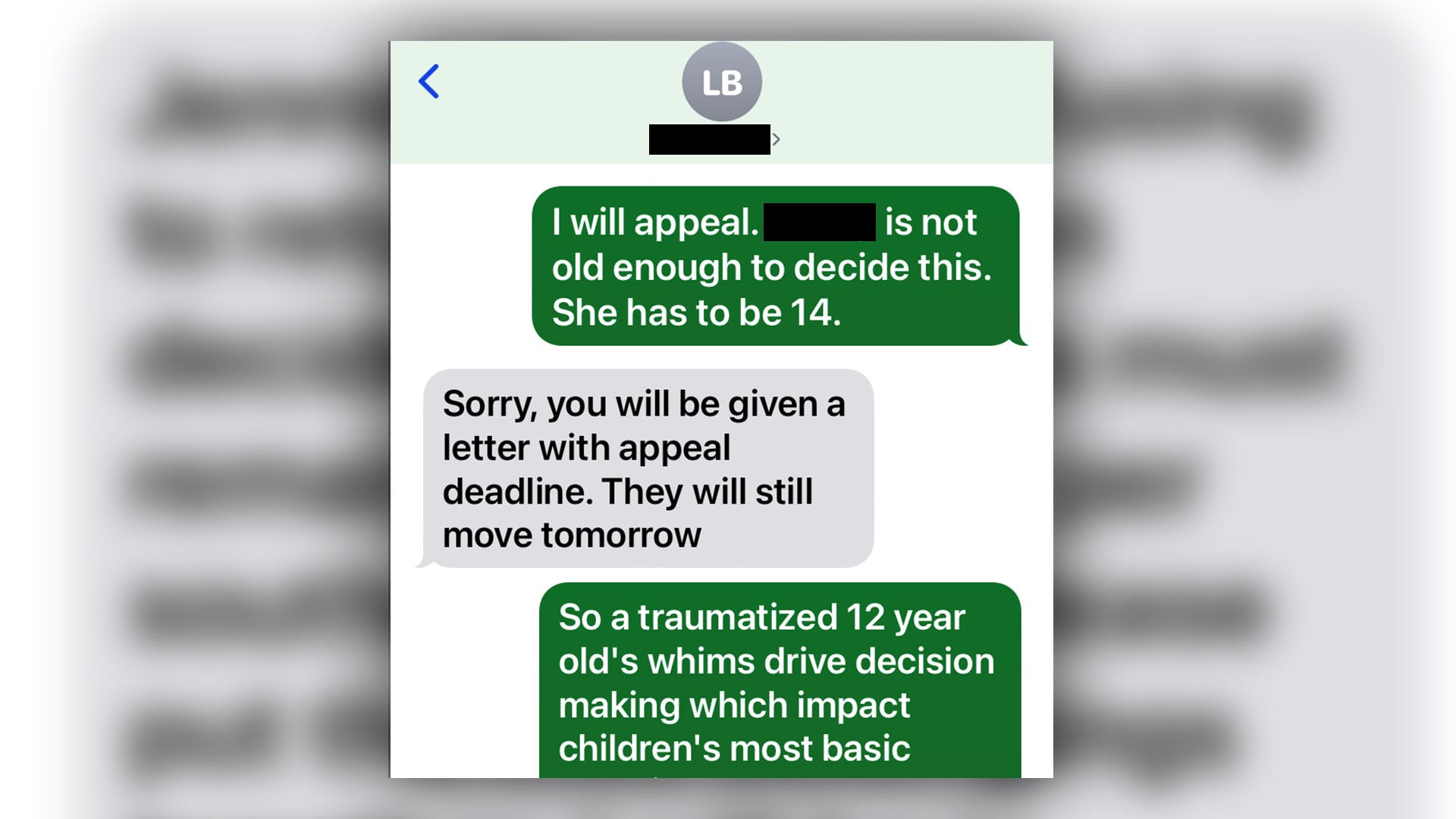

This following is an excerpt between Jennie Davies and a child welfare worker who abruptly told her children would be removed from her care because one of the children had run away after being given a curfew. The worker says all the children will be removed the next day because it is Southeast CFS policy to keep siblings together. Davies said she had three siblings but two others were in a different foster home so that policy is only applied when convenient.

It’s annual report for that year cites having 1,404 children in care, and boasts of returning 63 children to their families.

Its organizational structure shows it employs upwards of 150 Manitobans – mostly Indigenous – and had a budget of nearly $60 million in 2018. It’s just one of 23 agencies in Manitoba. Four child welfare authorities oversee them all.

“They misled me about the workload. Basically saying these five kids just needed structure. I couldn’t believe, actually, how they downplayed their needs,” she said.

Davies quickly realized she couldn’t accommodate two of the children who were sent to another home, leaving her with three children.

Things were fine for two years until the oldest reached age 12 and started pushing boundaries. When Davies wouldn’t budge on things like curfew, the child took off for a couple of day.

Davies recalls it happened on a Wednesday and Thursday in September 2020. The preteen was located by police on the Friday and asked to go to the home where her two other sibling were.

“I thought it was smart. Let her cool off. I had told her nothing has happened that can’t be fixed, don’t worry about it,” said the foster mom.

“Sunday morning I woke up to a text from the worker saying we’re picking up the other kids have them packed up. The kids are being removed.”

She breaks down when talking about telling the four and six year old that they would have to leave.

“I had to reassure them it was OK, nothing was their fault – it was devastating,” she says through tears. “And I haven’t seen any of them since.”

All five children have been at a foster home for the past two months with a single mother who has two children of her own. So seven kids to care for.

Davies pressed South East Child and Family Service about why they were removed, asked for them back and says she was told she could appeal the removal.

“I felt like I’d committed a crime,” Davies said. “Why are you treating people entrusted with the care of these kids, like that?”

She says the case worker told the supervisor that the kids were removed because Davies didn’t want the 12 year old and the agency’s policy is to keep children together – despite the family of five being separated into two foster homes for two years.

“This worker out and out lied,” Davies said. “I couldn’t believe it. Because I had the two younger children and couldn’t go out looking up and down the streets for her all night – and the police were looking for her – that was twisted to me refusing to care for her and not wanting her.”

She battled to set the record straight and fought for the return of the children but reached the point of defeat.

“They create chaos, they manipulate truths and when you call them on it they scramble and lash out. You’re constantly questioned and grilled,” Davies said. “Child welfare is not run by terribly healthy people. They will blow things up because they can, because they’re having a bad day – whatever. It’s sickening.”

Read More:

Devastated parents say incentivized apprehensions need to stop in Manitoba

Inside one family’s case why child welfare feels like a losing battle

It’s not lost on her that these same complaints are shared by biological parents whose children have been taken and placed in foster care

“There needs to be a better system because this one is not working. There are no checks and balances – these workers and agencies have the power to do whatever they want, without accountability, and they do,” Davies said.

Rhonda Kelly is the executive director of South East Child and Family Services.

She wouldn’t comment on specifics but says “we have measures in place that ensure workers be accountable” though she wouldn’t elaborate.

APTN News laid out in an email all of Davies’ concerns and offered Kelly or the agency the opportunity to respond to any or all. Neither she nor the agency responded, nor did they respond to a second email requesting comment or explanation.

Davies says the whole experience has led her to believe the child welfare system is the latest way to break Indigenous families – except now, it’s often Indigenous people doing it.

“This is no different than what’s been going on with Indigenous kids for a hundred year – forcibly removing them from homes without any care of what the effect will be,” the foster mom said.

Despite her experience in the child welfare system for 14 years, she says she might foster again some day.

Through tears she says, “I feel like I need to do it. To stand between them and this system. These little people need protection and to know that there’s someone there for them and they’re worthy.”