Fires rage outside Fort Chipewyan Cree Nation in northern Alberta. Photo: Danielle Paradis/APTN.

Fort Chipewyan resident Alice Rigney sits and participates in a crib tournament in the basement of the Nomad Hotel in Fort McMurray.

A number of elders are gathered around watching – looking for a distraction after a week out of their homes due to an evacuation order.

At home, a wildfire is still burning out of control less than 10 km from their homes.

“It is traumatizing when you are given three hours to pack a bag. You walk around your house and say… what am I going to take,” says Rigney.

“You don’t really have time to break down. I have two dogs and a grandson to worry about.”

Rigney is looking forward to being back home tending her garden when this is all over.

Right now, no one knows quite when that will be.

Three Indigenous communities, Athabasca Fort Chipewyan First Nation, Mikisew First Nation and the Métis of Fort Chipewyan have all moved south to Fort McKay First nation, or into Fort McMurray.

The evacuation started on May 30 for the fly-in community of Fort Chipewyan, about 730 km northeast of Edmonton.

Boats to the rescue

Around a dozen boats sit along the river shoreline after the evacuation. People are still coming in but the numbers have slowed to a trickle.

The trip up north to Lake Athabasca is five hours long. When residents received an emergency evacuation notice on May 30, 2023, some headed to the airport while others took to boats.

Some ran out of gas on the trip. It is nearly 300 km on the river.

Dennis Shott, a Fort McKay resident and one of the boat operators, has taken two trips down the Athabasca River to help evacuees from Fort Chipewyan.

He is one of many Indigenous people working to keep others safe during an unprecedented wildfire season.

“I was out on the river until one in the morning on the first night” Shott tells APTN News. “What got me the most is the elder people and the young kids, seeing the big smile when they realise we are helping them.

“I had 60 gallons of gas plus extra gas, and carrying big bags of water in the centre of the boat.”

The Indigenous communities along the Lake Athabasca Delta have been connected by these waterways for thousands of years.

When Shott heard about the evacuation, he asked his bosses at the Fort MacKay group of companies for time off and took to the river with a friend.

“We have to go back to the old ways of helping. Here we are connected by the water and connected by families,” says Shott.

When people landed, they unpacked their boats. Some Elders settled in Fort McKay and others made their way almost 60 km south to Fort McMurray.

The river levels are lower than in previous years, in part because of changes to the Lake Athabasca Delta from two dams on the river, owned by BC Hydro.

Climate change, hydroelectric damming and the nearby tarsands have all changed the way of life for Fort Chipewyan residents.

“Unfortunately over the past years we have seen extreme weather events increase,” said Prime Minister Justin Trudeau to reporters in Ottawa on Wednesday, “This year is the worst wildfire season we have ever had.”

The government pledged to be there to assist with the rebuilding efforts that will take place once wildfire season passes.

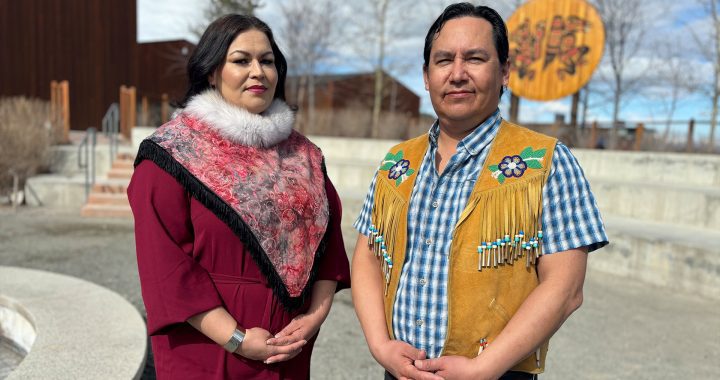

Chief Allan Adam has stayed behind in Fort Chipewyan along with Chief Billy-Joe Tuccaro and Métis local president Kendrick Cardinal. The three give daily updates to the community over Facebook Live.

“When you move 900 people you go through a lot when you see the chaos and confusion. You got people panicking so what do you do? Panic with them? If you do, it’s a lost cause,” says Adam tells APTN.

He says that issues keep plaguing the community. First, there was the Kearl tailings pond leak and overland spill, then the Mikisew Cree First Nation declared a state of emergency due to an increase in suicide attempts earlier this year.

“We already heard about how we would be environmental refugees. Well, here we are,” said Adam.

Read More:

First Nation in northern Alberta reports Kearl mine leak ‘worse’ than expected

While tailings pond leaked, Imperial Oil lobbied Alberta government on ‘cost-effective’ regulation

For now, houses in Fort Chipewyan are still safe. They are set up with sprinkler systems to help prevent the loss of life and property.

Numbers vary about how many people have stayed behind. The RCMP report 30-50 and other sources say it’s as high as 130.

The hamlet’s streets are mostly empty. The people who have stayed behind, like Herman Adam have been working to clear debris, clean up yards and secure the community.

“We are going to be working to the end, working to bring our community members home. That is our goal,” says Herman.

Other community members are out on the land, becoming recertified as firefighters.

Overall in Alberta, there remain more than 3,600 evacuees from Little Red River Cree Nation, Sucker Creek First Nation, Dene Tha’ First Nation, Mikisew Cree First Nation and Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation.

Meanwhile, at the cribbage game Rigney argues good-naturedly in Dene with her opponent as she takes an early lead.

“I hope I walk into my house again,” she says.