Few people agree on what the Assembly of First Nations should be or what strategic direction it should take, but two former candidates for the top job tell Nation to Nation if the AFN wants to go forward, it needs to change.

“It doesn’t seem like there’s any room for the grassroots people in the plan,” says First Nations policy analyst Russ Diabo, referring to the AFN’s policy document, The Healing Path Forward. “It seems to be driven by the chief and council system.”

Diabo ran for national chief in 2018, mounting a campaign that revolved around First Nations land rights, sovereignty and opposition to the Liberal reconciliation agenda. He skipped the AFN debate that year to join the Tiny House Warriors in British Columbia instead.

He continues to oppose the Liberal approach, and maintains the organization has a long way to go to gain relevancy and support from regular people.

“They have to do a lot,” he remarks. “From what I’m seeing, they’re consolidating the control from the top down, working through the bilateral mechanism that national chief (Perry) Bellegarde set up with the federal government.”

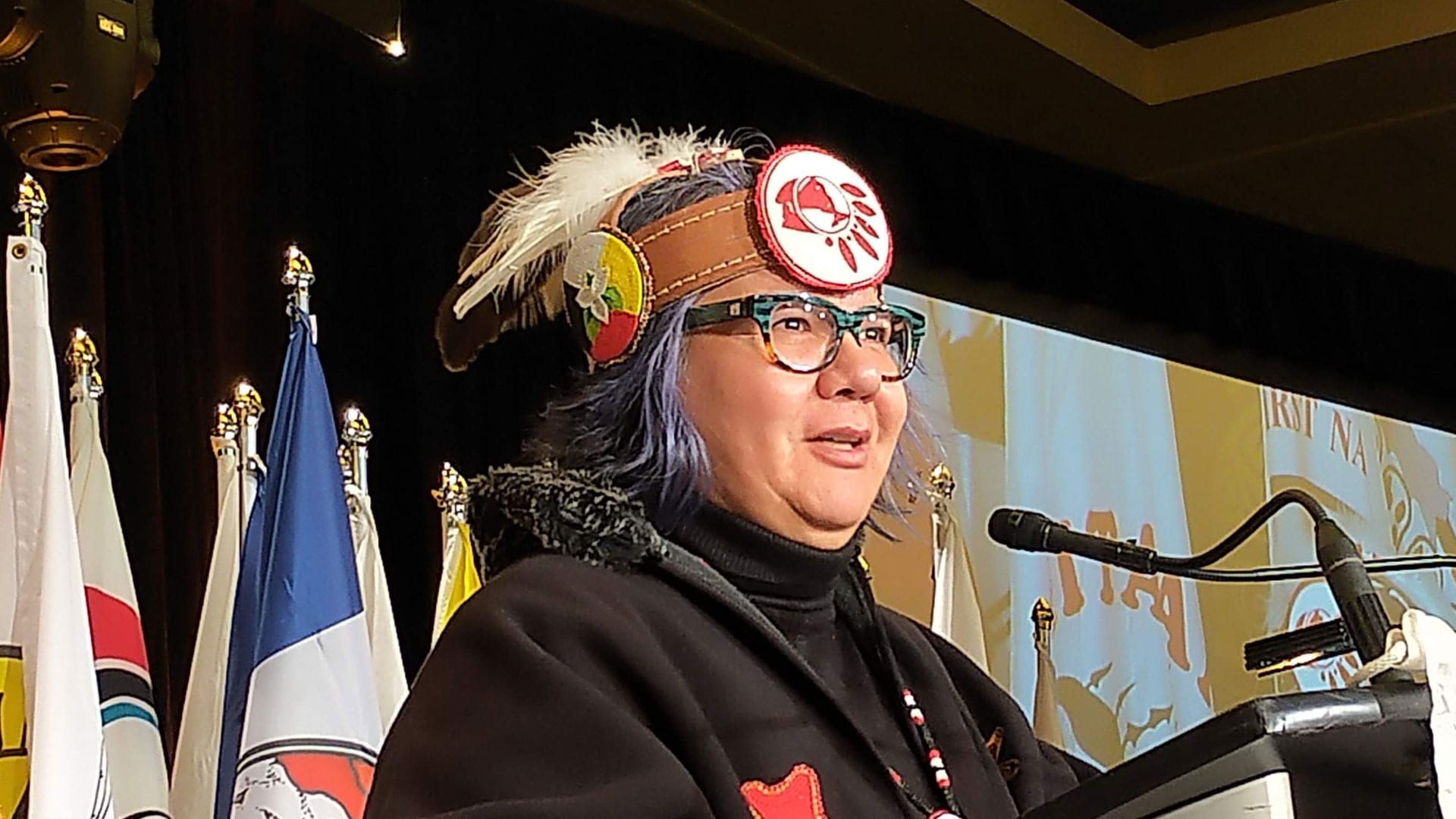

But Jodi Calahoo-Stonehouse, who campaigned to lead the organization this year, offers a more optimistic take.

“There’s so much potential, possibility and hope to revitalize and to bring back that love that our forefathers brought when they were advocating for our people,” she says.

Organization nearly four decades old

The AFN will mark its 40-year anniversary next spring. It was born at a 1982 gathering of the National Indian Brotherhood where the chiefs banded together to acclaim a national chief for the first time.

The federally funded lobby group has changed little since, though the election of the first woman national chief this summer was a historic shift.

RoseAnne Archibald’s first winter gathering as national chief concluded Thursday after three days, and Calahoo-Stonehouse says the former Ontario regional chief deserves some credit.

“I raise my hands to National Chief RoseAnne, as she brought forward a very ambitious plan,” says Calahoo-Stonehouse, executive director of the Yellowhead Indigenous Education Foundation. “For me, what I love and see is that she’s really lifting the role of women in leadership.

“We know that matriarchy has always been here. It’s been really beautiful that she has been brave to bring that forward. We are seeing resistance from our chiefs, as we know. Change is difficult and often painful.”

The delegates debated top agenda items such as proposed federal Indigenous health legislation, possible creation of a national treaty commissioner’s office, and a draft internal restructuring plan to separate politics from administration.

On Tuesday, Archibald announced an Indigenous delegation to the Vatican was put on hold due to COVID-19 fears. The chiefs also adopted a resolution to amend the AFN charter to include a two-spirit governing council.

But also on Tuesday lack of participation among the chiefs was brought into sharp focus. Only 25 votes constituted quorum to pass a resolution, while 634 First Nations were eligible. So what does that say about the status of the AFN?

“It doesn’t bode well, but that’s not a new phenomenon,” replies Diabo. “The assembly of First Nations quorum has always been questioned by chiefs over the years.”

“We can’t dispute, challenge, and/or lift up what we agree with if we’re not there,” agrees Calahoo-Stonehouse. “That falls on our leadership, and our grassroots people need to know that their leadership wasn’t there to represent them.”

Clean water class action seeks court approval

Meanwhile, First Nations and their members who’ve had to drink unclean water are on the cusp of resolving a national class-action lawsuit against Canada. A deal worth $8 billion sought court approval Tuesday, and a decision could be rendered early as next week.

It would dish out at least $6 billion over nine years for water infrastructure in communities. Canada would pay $1.5 billion to individual members. Another $400 million would go into an economic and cultural restoration fund.

Later on N2N, Chief Emily Whetung, one of three lead plaintiffs, explains what the settlement could mean for her community of Curve Lake First Nation in southern Ontario.

The community is surrounded by water, yet has had to truck it in at times due to a bad supply.

She says the deal would create a legal dispute resolution process so First Nations finally have ways to compel Ottawa to act.

“It becomes less and less important what the political promises are and it becomes more and more important that we have the ability to enforce real, meaningful access to clean drinking water,” says Whetung.

“It’s no longer political promises with moving targets. But if there’s issues, if there’s problems, there’s a mechanism to go and have those disputes resolved.”

Catch all that, plus an interview with Independent Sen. Kim Pate, above.