Statue by Haida sculpture James Hart called The Three Watchmen sits in the Byward Market area of downtown Ottawa. Photo: Mark Blackburn/APTN

The Canadian government claims the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) is an “interpretative aid only” that can’t be used to strike down federal laws even though Parliament has passed legislation requiring they be in sync.

Lawyers for Indigenous Services Canada (ISC) made the argument in response to a Federal Court challenge mounted by members of a Dene community in northern Alberta against the now-expired regulations that let First Nations postpone elections to deal with COVID-19.

The government, after losing a court case last April, retroactively validated these regulations in a section of the 2021 budget act — a section the group now asks the court to overturn.

“Around the time that they passed the budget bill, Bill C-15 came into effect,” explained the group’s lawyer Orlagh O’Kelly. “In UNDRIP, there is a requirement to consult with First Nations and Indigenous Peoples before passing legislation that impacts them. We say: That came into effect here and it wasn’t followed.”

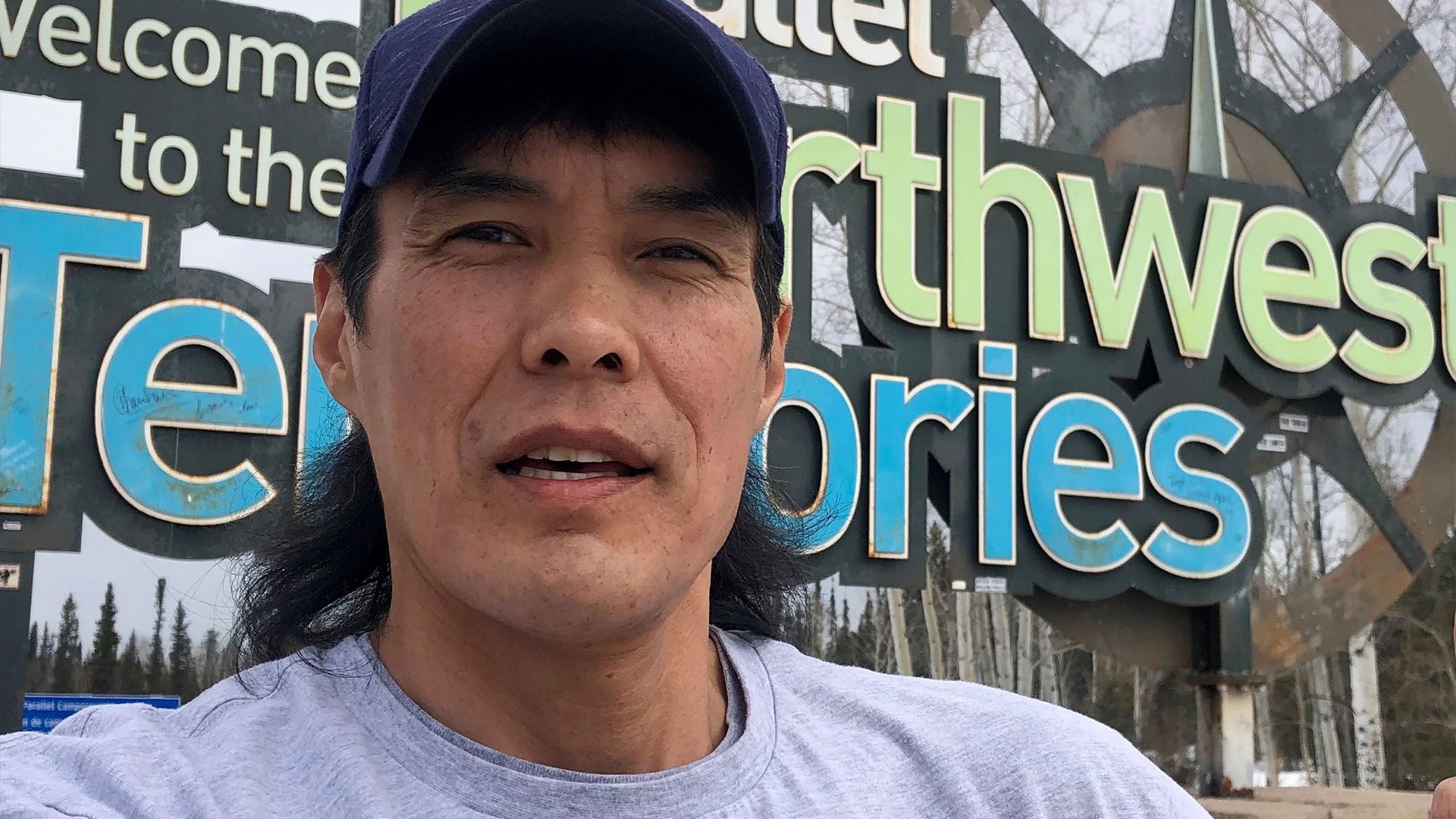

The case was filed by 49-year-old Sidney Chambaud and eight other members of the Dene Tha’ First Nation, about 850 kms from Edmonton, after their leadership used the regulations to delay the community’s October 2021 election.

In response, the government’s legal brief says UNDRIP “may be used as a contextual aid” in interpreting domestic law. “However, neither the UN Declaration nor the UN Declaration Act can displace the Constitution or clear statutory language, nor has any Canadian Court suggested that the UN Declaration itself has constitutional status.”

O’Kelly told APTN News she was “disappointed but not surprised” to see the argument, saying it seems to justify the critics’ “worst fears” about the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act.

Tabled in the House of Commons under bill number C-15, the act says the government “must take all steps necessary” to sync federal laws with the declaration. It received royal assent in June 2021 but not without substantial debate and some controversy.

Critics charged the statute would blunt the international instrument’s edge by subjecting it to Canadian common law, which already permits the infringement of Aboriginal rights, making it a toothless “legislative guide” the government may simply ignore.

“It’s disappointing, on that level, to see kind of an impoverished interpretation of what the new legislation implementing UNDRIP means in practice,” said O’Kelly in a phone interview. “People had high hopes for Bill C-15. Those who were cynical about it would say, more or less, ‘I told you so.’

“Again, it’ll be another interesting issue to see how the court receives that argument.”

Legal wrangle ongoing

Chambaud’s case is the latest development in a complicated jurisdictional and legal tangle that began when COVID-19 was declared a pandemic in March 2020.

As the novel coronavirus ripped across the planet, First Nations with looming elections feared potential consequences of in-person voting.

But as councils examined options, ISC told them they had to hold votes or let governance lapse into the band manager’s hands as the department had no authority to extend their terms.

ISC similarly told First Nations who select their leaders via custom election codes the department had no jurisdiction in this area and that “the final decision to maintain or to postpone an election is under your purview and must be made in accordance with your community governance code.”

The government flip-flopped a few days later by dusting off the Indian Act to produce the First Nations Election Cancellation and Postponement Regulations as a temporary stopgap measure to fight the virus.

But in Sec. 4, the regulations went beyond the Indian Act and authorized First Nations under custom codes to extend their term of office “even if the custom does not provide for such a situation.”

Floyd Bertrand, a member of Acho Dene Koe First Nation near Fort Liard, N.W.T., sued for judicial review after his band, which is governed by custom code, used the regulations to extend their term.

Read more:

Feds dig into the Indian Act to allow band councils to extend term during pandemic

Ottawa drops appeal in court fight over First Nations election postponement

Bertrand succeeded. The Federal Court concluded the Indian Act can’t override customary election codes, which, the court declared, are a form of self-government and like constitutions.

A judge ordered an election and deemed Sec. 4 of the regulations invalid. The government appealed but also promised to override the ruling by passing a special new law.

This was contained in the 2021 Budget Implementation Act, which retroactively declared the regulations and any decisions made under them valid.

But in overriding the court, Parliament also purported to again override the customary governance codes of First Nations, unilaterally empowering them to extend their term of office even if their codes don’t allow it.

Chambaud’s leadership in Dene Tha’ availed themselves of the newly affirmed regulations on Oct. 7 to stay in office until June 2022, according to court filings. The regulations expired the next day.

Chambaud alleges the government’s use of budget legislation on this issue violated both Aboriginal self-government rights protected by Sec. 35 of the Constitution as well as the new UNDRIP law.

He’s asked the court to strike down the disputed line in the budget act as illegal and order an immediate election. Chambaud told APTN he and the members backing him just want to vote; if they set a legal precedent, it’ll be a bonus.

“Things have got to go through members. Members are the ones that are in charge of who they put in place as leaders,” said Chambaud. “We’re standing up to this group of eight people: Their term has expired and us, as members, are asking to call elections.”

First Nation says decision reasonable

For its part, the Dene Tha’ band council argues the election deferral was “a reasonable decision” that falls under chief and council’s customary authority, saying leaders must occasionally make emergency decision without consensus or consultation.

“For example, clan leaders made decisions respecting the relocation of sick individuals when dealing with outbreaks of diseases such as Spanish flu, smallpox and chicken pox,” says the band’s legal brief. “Decisions to relocate during flooding in 1962 were also made by the Nations’ family leaders without consultation.”

The filing says there will be an election held June 2022, rendering the case moot. The First Nation also argues the nine applicants, who submitted a petition signed by 307 backers, don’t have representative legal standing to advance arguments about collective Aboriginal rights.

In its legal filing, Canada agrees with the mootness argument and contends a judicial review of a local governance decision is the wrong place to make complicated arguments about Aboriginal self-government rights and UNDRIP.

APTN contacted ISC asking the department to explain why its taking these legal positions but did not receive a response by publishing time.

O’Kelly acknowledges her clients are taking novel positions, but they’ve asked the court to hear their arguments — even if the case is moot — due to the issues’ substantial importance. To support the position, Chambaud’s filing quotes from a B.C. lower court ruling handed down in January.

“It remains to be seen whether the passage of UNDRIP legislation is simply vacuous political bromide or whether it heralds a substantive change in the common law respecting Aboriginal rights including Aboriginal title,” the judge opined. “Even if it is simply a statement of future intent, I agree it is one that supports a robust interpretation of Aboriginal rights.”

While made in the B.C. context, which has a nearly identical law, the courts must eventually face the question of whether Canada’s UNDRIP law is a vacuous political bromide or a tool for change, according to O’Kelly.

“How the courts use this legislation is really going to be telling,” she said. “There’s few cases to rely on, but thankfully some of them have quotes like that.”

The judicial review is scheduled for a hearing May 26. Chambaud looks forward to it, though he wishes there were a quicker way to resolve the dispute.

“It’s a frustrating point, a lengthy process,” he said, “but in the end it’s for a good cause.”