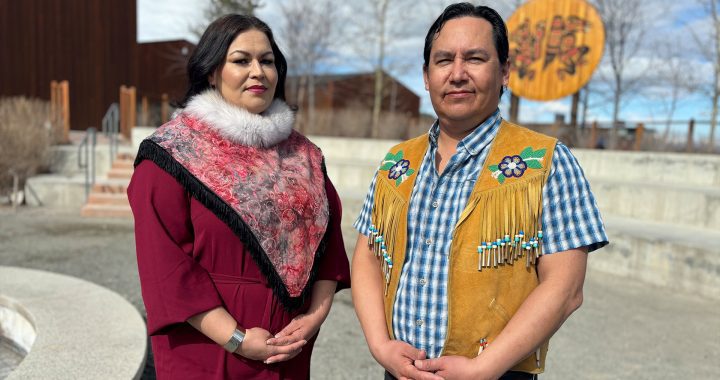

The chief of ?Esdilagh First Nation in British Columbia says changes to the province’s forestry plan are a step in the right direction that includes government-to-government engagement.

“First Nations and as well as other stakeholders have valuable input on what they would like represented and how that process would look,” says Chief Troy Baptiste. “This allows for forest landscape management that will improve the overall health and resiliency of the ecosystems help reduce the risk to biodiversity.”

On Oct. 20, the government introduced legislation that promises to reshape forestry management in B.C.

The changes will focus on sustainability and includes shared decision-making with First Nation governments.

The move comes after a year and a half of protests over logging of old-growth forests on Vancouver Island, calling for changes in forestry management.

Earlier this fall, Saik’uz First Nation near Vanderhoof in northern B.C. called for consent before any logging in their lands continued.

In 2020, the province promised a shift in managing the forests with the release and commitment to the Old Growth Strategic review.

In an interview with APTN News, Nathan Cullen, minister of Land and Natural Resources and former NDP MP, says the tools for managing forests were handed to forest companies decades ago.

“Much of the direction and authority had been given away to licences, to large forestry companies, he says. “Over the last 20 years, we have really seen the results; we lost 30,000 jobs, we have lost dozens and dozens of mills.”

Cullen says that the jobs have shifted to the United States.

“We see more and more investment by B.C. companies but not here in B.C.,” he said.

Bill 23, as it’s called, hopes to revamp forest management in the province.

The law governs how forest activities are conducted on Crown land.

It would shift decision-making power from industry back to communities and First Nations.

Minister Cullen says if the bill passes, the tools for old-growth management and deferrals can be put in place.

“What we’re doing is we’re working with Indigenous governments around B.C. because that was the first recommendation from the old-growth panel, is that we are engaging respectfully with the rights and titleholders. Not just running around with a map and a marker saying this is what’s going to be logged, this is what’s not going to be logged. Those are days past,” he says.

According to Baptiste, the previous policy and stewardship plan left little to no room for Indigenous input.

“We had nothing to do with it before, so this is all new to us it’s a learning process we’re going through,” he says.

?Esdilagh First Nation was recently included in forest landscape planning province with the province.

Baptiste says traditional knowledge and modern forestry practices can come together for health land for future generations.

“First Nations and as well as other stakeholders have valuable input on what they would like represented and how that process would look,” he says.

“This allows for forest landscape management that will improve the overall health and resiliency of the ecosystems help reduce the risk to biodiversity.”

Cullen says conflicts seen in the last 10 to 20 years in B.C. over resource projects or forestry cut blocks could have been prevented by having Indigenous communities be partners.

“Bringing people into the process very early on, respecting the right and title of First Nations and our obligations there will make for much better plans over the entire territory and landscape,” he says.

“That’s just our value’s being, expressed and that’s what we ran on in the last election.”

He says this legislation if passed, will provide clarity to industry, communities and Indigenous leaders.

The bill is now in the legislation process and is weeks from being passed.